CEO’s Sense of Integrity, Ethics Cited

- Share via

CALABASAS — Five years ago Brian Farrell suddenly stepped into the chief executive’s job at video game designer THQ Inc. He had his work cut out for him.

Founded in 1989 by Jack Friedman as a licensee and manufacturer of toys and video games, the company had lost its way by the mid ‘90s. The video game industry was moving from 8-bit to 16-bit systems, and THQ revenues had fallen from a 1992 high of about $50 million to $13 million in 1994. The company also reported losses of $15 million to $18 million per year from 1992 to 1994.

“I don’t know if we had negative net worth but it was darn close,” Farrell recalled. “Ever since that time there’s always been doubt as to whether THQ could survive.”

But few doubters seem to persist today. THQ shares rose more than 100% over the past year, and are now trading in the $44 range. And this summer, Farrell was named Entertainment Entrepreneur of the Year for the Greater Los Angeles Area by Ernst & Young LLP.

Fans say Farrell’s reputation for candor has been a big part of his success.

“I think that’s why he gets such a warm reception from investors,” said Stewart Halpern, an analyst with Banc of America Securities who follows THQ. “People appreciate a guy who’s giving it to you straight. And his company really delivers what they say they are going to deliver.”

“Brian just proves that nice people can finish first,” said Fred Gysi, THQ’s chief financial officer. “I’ve known him for 20 years and he’s basically the same person that he’s always been. He brings a sense of integrity and ethics to whatever he does.”

Farrell was hired as THQ’s chief financial officer in 1991, shortly before the company’s initial public offering. But when Friedman left in 1995, the board of directors turned to Farrell to take the top job.

By this time, the video game industry was already ramping systems up to 64-bit players, such as the Nintendo 64 system.

THQ didn’t have the assets or credibility on Wall Street to be able to play ball.

“We knew we couldn’t compete, so we decided to follow the technology curve for a year or two and stay with the older systems,” Farrell said.

Farrell set up meetings with THQ’s partners in video game development--including Walt Disney Interactive, LucasArts, Saban Entertainment (producers of Power Rangers) and Viacom’s Nickelodeon and MTV divisions. His mission was twofold: to negotiate to lower the company’s debt to its licensors and, at the same time, convince them to commit to new product license deals.

“It was interesting saying things like ‘I can’t pay you the $200,000 I owe you, but we’d still like to do business with you’,” Farrell said. He’d start the meetings by opening his books to his creditors. “I said, ‘Here’s our payment plan, here’s our cash flow.’ We were trying to create the reputation that we’re an honest company.

“We made the same deal with everyone and we stuck to it. I’ve always been taught that both in life and in business, you do what you say you’re going to do.”

The toughest part, he said, was cutting the staff in half, down to 30 people, and shrinking office space. “I don’t think this is a fair comparison, but like a child who grew up in the Depression, I don’t ever want to go back there again.”

But in the midst of all this angst, the business plan that Farrell and his executives mapped out was solid. After securing licenses for games for older game systems, they hit the market with greatly lowered prices (averaging $9.99 to $14.99, as compared with $40 to $60 for games for the new systems). Revenues grew back to $33 million by the end of 1995. “It was a tough business model, but if there’s a market there, why not service it?” Farrell said.

And still many doubted whether THQ could jump back into creating games for the cutting-edge market. “We became so successful at selling these older games, THQ became known as the old technology company,” said Farrell. “That’s not good if you’re trying to get a better evaluation on Wall Street or attract investors.”

So Farrell made the decision to invest the money they were making in some games for the newer 64-bit systems. They scored big by striking a deal with the World Championship Wrestling. By the Christmas season of 1997, they had a runaway hit with a Nintendo 64 product called “WCW versus NWO: World Tour.” By the end of the year, the company’s revenues were up sixfold to $90 million.

The victory would be short-lived. By March 1998, THQ had lost the World Championship Wrestling license in a bidding war with Electronic Arts and the company’s stock price plummeted 40% in two days.

“It was an overreaction,” said Banc of America’s Halpern. “I knew that when Brian Farrell said they had plenty of product coming down the road, that it was true.” Halpern reiterated his strong recommendation on the company.

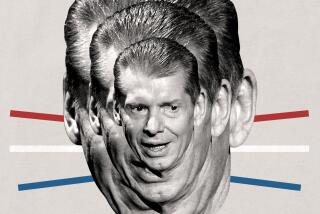

Farrell said he was determined to stay the course and keep investing in other kinds of programs. They picked up the game license for “Rugrats,” not necessarily the kind of program that appeals to the traditional video game buyer (at the heart of the market are boys, ages 11 to 17). It turned out to be a surprise hit. The company also nabbed the license for the World Wrestling Federation, the competing organization to the WCW. “Not only have we replaced the WCW license, but we feel we now have a better license,” Farrell proudly said.

And throughout it all, Farrell has not forgotten the hard lessons learned when navigating a company away from financial ruin. Up until this week, he’s kept the company’s headquarters at the same less-than-lavish Calabasas address as when it started 10 years ago. But success is catching up, and the company is moving this week to larger quarters, still in Calabasas. And he’s cautious about growing the company, which employs 250 people, into new areas such as games for PCs, which make up only 10% of the company’s business. “That’s the CFO in me,” he joked.

But the CEO in him is pushing the company toward new product lines. THQ will soon make its first foray into original products, as opposed to products licensed from other companies. And Farrell said he continually looks for ways for the company to take creative risks without losing sight of budgetary concerns.

“Sure, when we were a $30-million company we couldn’t take risks on original product,” Farrell said. “Now that we’re a $300-million company, we can’t afford not to take those risks.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.