Julian Carsey; Educator Vanished Twice and Began Brand-New Lives

- Share via

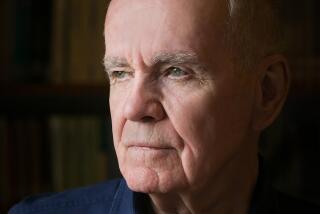

Julian Nance “Jay” Carsey, a former Maryland college president who shed identities like old clothes in an enigmatic quest that made headlines and became the subject of a best-selling 1989 book, died Aug. 20 at his home in Jacksonville, Fla.

He was 65 and had suffered from liver problems.

Carsey was the charismatic president of Charles County Community College in Maryland who was days away from leading the school’s commencement exercises when he disappeared in May 1982. He left behind his wife of 14 years and a 23-room mansion filled with antiques and exotica from their world travels. He also left a few terse notes, including one to a co-worker that said simply: “Exit the rainmaker. Good luck. Jay.”

He moved to El Paso, where he roomed in a YMCA, eventually becoming an administrator at El Paso Community College and marrying a social worker. But, after several years, he dropped out of that life, reinventing himself in another town hundreds of miles away.

None of his behavior had broken any laws. But it bewildered those close to him, who wondered how a once-golden boy could turn out to be a fraud.

His sudden exits from carefully nurtured lives caused people to debate: Was he an adventurer who dared to do what most people only dream about? Or was he a coward, too weak to confront the unhappiness in his life?

“I personally think you’ve got to totally distance yourself from the past that you’re leaving,” Carsey said in one of his last interviews, which aired on ABC last year. “You’ve got to do the guillotine approach. You’ve got to say, ‘OK, that period of my life is in the past.’ ”

When Carsey disappeared in 1982, he was in his 17th year as president of Charles County Community College. A Texas native, he had a degree in business administration and chemical engineering from Texas A&M; University and a doctorate in public administration from George Washington University.

He arrived in Charles County in 1958, working as a chemical engineer at the Naval Ordnance Station at Indian Head and teaching part time at the college.

In 1965, he rose to become college president. He was only 30, one of the youngest college presidents in the country.

In a short time he expanded the college’s offerings in environmental studies and waste-pollution management, which attracted lucrative government grants.

The mansion he lived in with his wife, Nancy, was big enough to have a name: “Green’s Inheritance.” It was so full of expensive and unusual souvenirs from their exotic vacations that locals called it Smithsonian South.

But none of it was enough. Or perhaps the opposite was true--it was too much. On May 19, 1982, he left home, telling Nancy that he might return for lunch. Noon came and went, but Carsey never showed.

In the days that followed, it became painfully apparent that foul play was not the cause of his disappearance. He left a note for Nancy in which he said he was “a physical and psychological disaster . . . and I don’t want to drag you down with me.” He took $28,000 from a savings account, leaving the estate to her.

In a note to colleague John Sine, the college dean who would succeed him as president, Carsey alluded to a role in the N. Richard Nash play “The Rainmaker,” which he once played in a production directed by Sine. The play concerns a man who deserts his community and the woman who loved him.

It inspired the title of the book that journalist Jonathan Coleman would write about Carsey’s first disappearance, “Exit the Rainmaker.”

Carsey resurfaced several months later in El Paso. His cover was blown when People magazine ran a story about his disappearance in Maryland. But the notoriety did him no harm in El Paso, where the community college was eager to hire an administrator of proven talents.

He obtained a divorce from Nancy Carsey and lived for several years in El Paso, where he married a woman who directed a program for the elderly.

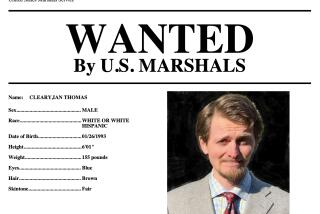

Then, three days before Christmas 1992, he downed a cup of coffee, blew a kiss to his wife, Dawn, and, without a word about his intentions, was gone for good. A letter granting Dawn power of attorney over their finances came in the mail. It began, “To whom it may concern . . . “

The letter was postmarked Jacksonville, Fla., where Carsey lived with his companion of seven years, Corinne Silverton, until his death.

Why did he leave?

In Maryland and in Texas, his timing seemed strategic. Just before his disappearance from Charles County, he was facing budget tightening and massive layoffs at the college. Before his exit in El Paso, he had been worried about physical deterioration; his eyesight and hearing in particular were failing. Moreover, he had a drinking problem that seemed to be spinning out of control.

Yet, there remained some part of Carsey that could not be explained by concrete reasoning--an awesome quirk that his first wife once attempted to describe as “a little box somewhere that I didn’t enter.”

Carsey, Coleman said in an interview last year with ABC’s Connie Chung, was “a bit of a con man,” like the character Burt Lancaster portrayed in the movie version of “The Rainmaker.”

“Jay . . . really saw himself in life that way, as somebody who had great vision, that he could make things happen. They engender a great deal of loyalty and love,” Coleman said. “But rainmakers don’t stay around forever. They take off. And then, all of that energy and charm is taken somewhere else, and the show begins again in another town.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.