He’s Caught Short in the Draft

- Share via

If you just look at the numbers, Rik Currier would have been selected by someone in this week’s baseball draft.

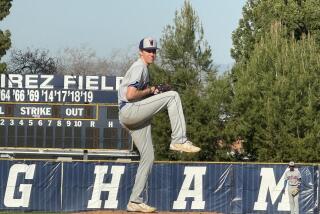

Currier, who is from Dana Point, is a junior at USC. He is the ace of the staff who will pitch the opener for the Trojans today against Florida State in the College World Series.

Currier has a 14-3 record this year and a 3.22 earned-run average. He is third on USC’s all-time strikeout list with 325, ahead of Randy Johnson (206) and Bill Lee (211). Last summer, he was pitcher of the year in the Cape Cod League, where the best college players go and play with wooden bats.

Currier throws his fastball between 88 and 91 mph. He has a changeup that dances and a slider that is wicked.

All those numbers, facts and figures are impressive.

But Currier wasn’t drafted. Not by anybody, not through 50 rounds.

He is, it turns out, too short.

Did you know there is a height requirement to be a professional right-handed pitcher? Apparently there is. Currier has heard about this requirement, early and often.

“Only all my life,” Currier says. “If only I was a couple inches taller. I hear that all the time.”

Currier is 5 feet 10 inches tall. That’s normal for most men. But major league teams want their pitchers bigger. At least their right-handed pitchers.

“If Rik were a lefty,” USC Coach Mike Gillespie says, “he’d have been drafted in the first five rounds. But he’s not, so the scouts say they can’t draft him. The 5-10 right-hander doesn’t pass the ‘look’ test. Rik is not the prototype 6-3 to 6-7 pitcher. That’s the professional pitcher. Period.”

Gillespie first got to know Currier when Currier was a junior at Capistrano Valley High. What Gillespie saw was this rather short, kind of squatty kid with a slider. A very good slider. “The kind of pitch,” Gillespie says, “that you just don’t see high school kids throwing.”

“I can’t take credit for that slider,” says Bob Zamora, the Capistrano Valley coach.

“I couldn’t believe that slider either,” Zamora says of the first time he saw Currier pitch. “You just don’t see a high school kid throwing sliders. Rick learned it from his Little League coach at La Mirada.”

The pitch came to him easily, Currier says. It didn’t seem particularly hard for him and he didn’t think he was particularly special.

Currier started playing baseball when he was 5. He became a pitcher as soon as possible. “I liked having the ball in my hand,” Currier says. “I liked the thinking part of pitching.”

When Little League coaches started telling him he might want to think about playing other positions, that he just wasn’t going to be big enough to pitch, Currier ignored them. Why should he believe that? If he could get everybody out, if he could strike people out and win games, why shouldn’t he be a pitcher?

“I don’t understand it,” Currier says. “The scouts I’ve talked to all say the same thing. They tell me they like my arm, like my slider and changeup, that my speed is fine. And then they say, ‘But . . .’ ”

The pitchers Currier respects the most are Atlanta’s 6-foot Greg Maddux and Boston’s 5-11 Pedro Martinez. It is no coincidence that neither is a giant.

“It’s hard for Rik,” Gillespie says. “Rik has quite a special breaking pitch in his slider. He has really, really improved the quality of his changeup. He has a true three-pitch mix. If he gets you deep in the count, he can throw any of those three pitches to get you out.”

Zamora has a 6-2 son, Pete, who pitched a perfect game Wednesday night for the double-A Reading Phillies. “What a lot of it is with height,” Zamora says, “is arm angle. When you’re 6-5 and throw 90 mph-plus, you have a sharper angle on the pitch. A guy who’s 5-10, the ball is going to be flatter. Rik’s got a good fastball, but it doesn’t have the same movement on it you’d see on a guy who’s taller.”

Currier thought his success in the Cape Cod League would help him get drafted this year. He hoped to get picked in the first five rounds and get a decent signing bonus. “I felt I deserved to be picked there,” Currier says. “But I guess I didn’t expect it.”

This summer, Currier will stay home, go to summer school and play ball in a summer league Pete Zamora plays in, an adult league. Currier wants to graduate on time with his degree in economics. Then he’ll pitch one more season for USC.

Then?

“I will sign with someone,” Currier says. “I’m convinced I can pitch in the majors.”

Says Gillespie: “In five years, I expect to see Rik on a big-league roster. He’s just going to have to prove himself.”

As always.

Diane Pucin can be reached at her e-mail address: diane.pucin@latimes.com

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX / INFOGRAPHIC)

USC Career Strikeouts

*--*

Name Years Strikeouts 1. Seth Etherton 1995-98 420* 2. Brent Storm 1968-70 363 3. Rik Currier 1998-2000 325 4. Randy Flores 1994-97 316 5. Randy Powers 1987-90 312

*--*

* NCAA and Pacific 10 record

More to Read

Fight on! Are you a true Trojans fan?

Get our Times of Troy newsletter for USC insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.