Horseshoe Crabs, Nature’s True Bluebloods, Save Human Lives

- Share via

CHINCOTEAGUE ISLAND, Va. — In a small unmarked building on a back island road four miles off the coast of Virginia, the bleeding begins.

Hundreds of strange, spiked creatures are pinned to plastic racks as lab technicians in white coats and facemasks glide from row to row, rubbing them with alcohol as though soothing them for their ordeal.

The creatures flinch as long surgical needles are inserted into creases in their helmet-shaped shells. Blood spurts into bottles beneath them.

Rich and blue, it is precious as gold.

And every day it saves lives around the world.

No other creature can produce this substance, the world’s only known source of a compound used to test for contaminants in every drug and vaccine, every artificial limb and every intravenous drip in every hospital in America. Science can’t make it either.

Only the horseshoe crab, one of the oldest living animals, older than dinosaurs, so old it is dubbed a “living fossil,” produces this magic.

And only in recent decades have scientists begun to fathom its power.

*

The moon is a dusty orange ball that hangs low over the ocean, so low the two fishermen joke they could reach out and catch it.

“C’mon, moon,” the younger one howls from the deck, willing it to brighten so the work can begin. He complains they have set out too early, that horseshoe crabs feed later, when the moon is full.

Leon Rose, skipper of the 47-foot trawler Christopher, ignores his grumbling shipmate. A storm the night before forced the crabs to bury themselves deep for safety. They’ll be hungry tonight, he reckons. They’ll dig out early.

Rose is sturdy and square-jawed and stoic. He’s been fishing the waters of the Delaware Bay most of his 57 years. He knows exactly where to drop his massive 70-foot nets: a mile and a half from shore, the lights of Ocean City twinkling in the background.

Thirty minutes later the deck is a glistening, writhing mass of claws and fins and feelers. Jellyfish and starfish, angel shark and conch. Ghostlike underbellies of skate. And horseshoe crabs, mountains of them, all shades of gray and brown, like an army of miniature tanks, clawing over each other, slithering in every direction across the heaving boat.

The fishermen work fast, scooping the bigger crabs into plastic crates. Young ones are flipped back into the ocean, along with other fish. Then the men drop the nets again. A few more hours trawling and they’ll make the lab’s quota of 1,000 crabs this summer night.

Fifteen years ago, when he turned to horseshoe crabs after a lifetime of clamming and scalloping, Rose was ashamed to admit what he fished for. Horseshoe crabs were considered the trash of the ocean, dumped overboard with monkfish and other junk.

Today the ocean’s trash has become its treasure, prized not just for its blood but also as bait for lucrative overseas conch and eel markets. And Delaware Bay, the world’s prime spawning area, is the biggest treasure trove of all. Here the crabs have become so hunted that states have imposed restrictions on the numbers that can be caught, and the federal government has proposed turning the bay into a preserve.

The proposals don’t affect Rose, the only fisherman licensed by Virginia and Maryland to catch horseshoe crabs for medicine--and the only one who returns his captives live to the ocean, 24 hours after their ordeal.

“We aren’t just fishing,” Rose says, pushing crates of wriggling crabs across the deck. “We’re saving human lives.”

Bleeding for Science

Chincoteague Island is a tiny, wind-swept place, more famous for its wild ponies than horseshoe crabs. It is here that Rose brings his nightly catch, to a small building in a residential neighborhood on Bunting Road.

The BioWhittaker laboratory bleeds about 100,000 crabs a year, all of them caught by Rose. The process is fast and, say lab officials, painless.

The crabs are hosed down and sorted by size: the largest are about 2 feet long and weigh 10 pounds. The bleeding lasts a few minutes. Drained of about one-third of their blood, the creatures are tagged and tossed back into crates. Most survive.

That night Rose will collect them for their journey back to the deep.

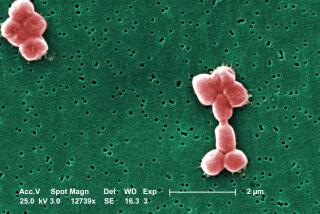

After the bleeding, the science begins. The sapphire-blue blood is centrifuged to separate white cells from plasma. The white cells are then ruptured to release a protein, which is mixed with other ingredients and made into a freeze-dried powder called Limulus Amebocyte Lysate. LAL, as it is known, is sold to pharmaceutical companies around the world.

LAL was discovered in the early 1950s by a scientist named Frederick Bang. It became widely used in the 1970s. Before then, drugs were tested for contaminants by injecting a sample into a rabbit. If the rabbit got a fever or died, the drug was discarded.

Today, LAL is the most effective way to screen for contaminants in drugs and medical devices. Since 1987 it has been the required FDA test for all drugs used by humans.

The test is simple. The powdered LAL is rehydrated and a small sample of a new drug is dropped into the solution. If the drug is contaminated, the mixture will clot instantly.

Science still hasn’t figured out a way to make LAL synthetically.

“We’re slugging it out with the rest of them,” says William McCormick of BioWhittaker, referring to the four U.S. companies that bleed horseshoe crabs and their efforts to find an alternative. BioWhittaker is the largest of the companies.

“Their blood is very complex, very sophisticated,” McCormick said. “And right now, it’s simply the best we have.”

The industry bleeds about 300,000 crabs a year, producing about $50 million worth of LAL, according to analysts. BioWhittaker bleeds between 600 and 1,000 crabs a day during the bleeding season, which lasts from about April to October. It makes about 600 liters of LAL a year.

Like other companies, BioWhittaker is as secretive about its process as it is about profits. There are no signs outside its building. The closest visitors get to the bleeding room is a peek through a glass door.

“You look at these creatures every day and it’s like going back in time,” says Jan Nichols, peering through that door at the crabs being placed on the racks. “No other animal contributes so much to science without dying in the process.”

Nichols has worked for the lab for 12 years. She knows horseshoe crabs as well as anyone, knows the species is not really a crab at all, but more related to spiders and scorpions. Nichols brims with admiration for the creature she calls “perfect”--so well adapted to its environment that it has not had to evolve for millions of years.

But it wasn’t until a year ago, lying in a hospital bed, an intravenous drip in her arm, that Nichols truly appreciated their perfection. She was fighting cancer. They helped save her life.

“Every drug they gave me had been tested with the blood of the horseshoe crab,” she said. “And I thought, what an amazing creature I work with. What a contribution it makes to human existence.”

These day Nichols wonders, as many others do, just how long their contribution will continue.

To the Beach to Reproduce

Every spring, when the tide is high and the moon is full, millions of ancient creatures crawl ponderously from the deep. They blanket East Coast beaches with their pearly green eggs. Then they creep back to the waves.

The birds swoop down, swarms of them: red knots, sanderlings, ruddy turnstones, gorging themselves on eggs to fuel their journey north.

The commercial fishermen sweep in, cleaning the beaches of thousands of crabs in a few hours. Female crabs are particularly prized as bait for conch and eel. The tourists come with their cameras. The researchers come with their notepads.

Suddenly a mating ritual that hasn’t changed in 400 million years is being threatened.

Earlier this year, most Atlantic coastal states restricted by 25% the numbers that can be caught. The National Marine Fisheries Service declared a moratorium on commercial horseshoe crab fishing in Virginia when that state refused to reduce its quota from 710,000 crabs to 152,495. And in August, the federal government proposed turning Delaware Bay into a national preserve.

Environmentalists say over-harvesting of the crabs has endangered rare migratory shorebirds whose survival depends on a Delaware Bay stopover. They also worry about the long-term effect on the crab population. In Japan, once another prime spawning area, overfishing has virtually wiped them out.

But fishing interests argue that the crabs are vital to the local bait business and that there are no indications of a serious decline.

The biomedical companies watch the debate anxiously, worried not just about the supply of blood. The horseshoe crab’s eyes are used for research on human eyes. The chitin from their shells is used for sutures.

“We are talking about the survival of a species that is ecologically, economically and medically vital,” says Jim Berkson, assistant professor in the Department of Fisheries and Wildlife Sciences at Virginia Tech. “And no one really knows what is going on.”

Berkson and his assistants have tagged some BioWhittaker crabs to track their movements. They’ve counted crabs on beaches during spawning season. But the research is in its infancy.

Berkson believes the crab population is in trouble, although evidence is mainly anecdotal--from fishermen who say they have to travel farther to catch them, to beaches swept clean at spawning time. That, says Berkson, is particularly troublesome because the crabs take so long--10 years--to reach sexual maturity.

“These are the most incredibly resilient, tough, fascinating creatures,” Berkson said. They have survived more than 350 million years. They could survive a nuclear explosion. The only thing they won’t survive is human greed.”

From Whence They Came

The ocean is dark when Leon Rose and his mate, Bryan Adams, lug the crates from the dock onto the Christopher. Rain pours down. The wind picks up. There’s a storm blowing in from the north. The crabs will bury deep tonight.

They load the trawler anyway, and head out of the harbor.

A mile from shore, Adams plucks a large, barnacle-encrusted creature from a crate. A white identification tag is punched into its shell.

“Female,” Adams says. “Probably 20 years old.”

Solemnly, he raises the old crab above his head.

“What the sea grants, we shall return,” he shouts into the spray.

Then he casts the prehistoric lifesaver back into the deep.

*

Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission:

https://www.asmfc.org/

U.S. Dept. of Commerce National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration NOAA Fisheries: https://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.