Dry Details Obscure the Lure of the Enigmatic Hildegard of Bingen

- Share via

Hildegard of Bingen is an enigmatic saint, perfect in many ways for modern-day hagiography because her legend is shape-shifting, open to the modification of those who would claim her. The 12th century mystic, physician, musical composer, artist, science writer and abbess--subject of Fiona Maddocks’ biography “Hildegard of Bingen: The Woman of Her Age”--has gained prominence in recent years among a wide swath of spiritual seekers, due in part to the pliable nature of her tale and the breadth of her interests.

In recent years, Hildegard’s music has topped the CD bestseller charts. Web sites that explore, and in some cases misuse, the mystic’s writing and music now litter the Internet. Hildegard has become the spiritual defender for environmentalists, gays and lesbians, feminists and many on the fringes of orthodoxy as well as those in the mainstream, all for different reasons. Even the issue of her sainthood is in question: She was referred to as a saint as recently as 1979 by Pope John Paul II, but she has never been canonized.

Hildegard herself was a staunch conservative, Maddocks tells us, a loyal papist and resolute moralist who might have been appalled by the way her words, music and legend have been expropriated by those who profess her guidance. With this biography, Maddocks takes on the questions of who the real Hildegard was, looking particularly into how, when and even if Hildegard created the scientific and theological writings, musical compositions and artistic works credited to her.

Hildegard’s talents were wide-ranging, often transcending the limits imposed on the women of her time. She entered a male monastery at the age of 8--”at birth, her parents had promised her as a tithe to the church”--and lived as a hermit under the care and direction of another female hermit, Jutta. Later, she established and became the abbess of a thriving convent community and was a correspondent with popes and other theological leaders of her age. She is said to have produced major works of theology and to have preached publicly (an act from which women were almost always excluded); written important books on science, natural history and the use of herbs as medicines; and compiled a book of her apocalyptic visions, “Scivias,” which includes detailed illustrations of her visions.

Unfortunately, Maddocks’ biography becomes so inundated with pinning down the details of Hildegard’s life and travels--what she is said to have done and what she actually did, as best postulated by scholars 800 years after the fact--that readers may have a hard time imagining the real-life Hildegard, seeing instead only the debated particulars surrounding her life.

Last summer I attended a sacred arts festival sponsored by the Benedictine monks of St. Andrew’s Abbey of Valyermo, during which I participated in two seminars on Hildegard. From those seminars--one on her musical compositions, the other a play that explored her concept of “viriditas” (greening), the ongoing spiritual blooming and regenerations about which she often wrote and preached--I encountered Hildegard as a moving, living, vibrant persona whose attributes might be emulated. Were it not for this firsthand encounter with the Hildegard myth, I might never have understood from Maddocks’ biography, with its lists of facts, references and conjecture over scholarly points, the potent Hildegard whose story has grasped the imaginations of so many. In this biography, the mystic becomes a fossilized subject of study, much like an archeological ruin to which little imagination is brought. Even the music, for which Hildegard is most famous, is given short shrift by Maddocks, who is herself a music critic.

Rather, the narrative is framed with the mortal remains of Hildegard. “Through the golden fretwork, a skull wrapped in faded muslin and covered in ruby-colored stones can be glimpsed, empty eye sockets staring out blindly,” Maddocks writes of her encounter with the holy relics at the parish church of Eibingen, Germany. “If you kneel on the altar steps long enough, you can make out two small, curiously shaped boxes, also jeweled and embossed, containing Hildegard of Bingen’s heart and tongue. Few writers can be said to come face to face with their subjects in quite this way.”

The book Maddocks has written is as dry as the remains themselves, and though a few jewels bring glitter (that Hildegard believed in griffins and dragons, for example, and credited pelicans with prophetic powers), they’re a poor substitute for vitality. Scholars of Hildegard may be engaged by Maddocks’ exposition of the current debate on various aspects of the mystic’s legend. The average reader, however, may find the esoterics mind-numbing and the pull of Hildegard’s charismatic power overlooked amid Maddocks’ examination of historical bones.

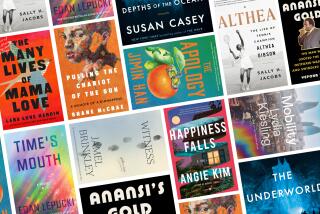

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.