In Calcutta, a Postmodern Man in Search of a Soul

- Share via

Born in Calcutta, raised in Bombay, a graduate of University College, London, who received his doctorate from Balliol College, Oxford, Amit Chaudhuri has won high praise for his subtle, unhurried depiction of ordinary life. He has also won numerous awards, including last year’s Los Angeles Times Book Award in fiction for his “Freedom Song,” a collection of three short novels.

In an age in which many writers are doing the literary equivalent of handstands to catch our attention, Chaudhuri proceeds with quiet, unobtrusive confidence to seek out the hidden poetry of banal encounters and routine events. Although some critics have described his approach as “Proustian,” the comparison is misleading. When Proust devotes many pages to evoking the complex emotions felt by a little boy awaiting his mother’s good-night kiss, the effect is not, as some have maintained, “exquisitely boring,” but profoundly revelatory. Time and space are expanded. Proust really does show us, in the words of William Blake, how to “see a World in a Grain of Sand.”

Chaudhuri proceeds by elision rather than inclusion. Although his latest book is called “A New World,” the world it depicts is spare and subdued. Not only are there no grandly dramatic events, but there is little sense of the characters’ internal lives. Yet, rather amazingly, this low-keyed account of a divorced man and his son spending a dull vacation in Calcutta with the man’s parents manages to keep us turning the pages.

Thirty-eight-year-old Jayojit Chatterjee is an economics professor who had been living with his wife, Amala, and son Vikram, nicknamed Bonny, in the American Midwest. Theirs had been an arranged marriage, apparently amicable. When Amala walked out, taking their son to San Diego, Jayojit was not only surprised but also sufficiently roused from his usual placidity to insist on partial custody. Bonny, now 7, is a quiet, withdrawn little fellow who is all too accustomed to being shunted back and forth. In a taxi from the airport to his grandparents’ home in Calcutta, he stares out the window, “as if a taxi were the most natural place for him to be in.”

Jayojit’s father is a retired admiral, “one of those men who, after [India’s] independence, had inherited the colonial’s authority and position, his club cuisine and table manners . . .” The Admiral’s wife is a diffident woman who knows her place. Both are adjusting to the somewhat reduced circumstances of his retirement: smaller living quarters, smaller income, only one servant who comes in occasionally. Although not very experienced in the kitchen, the Admiral’s wife has wholeheartedly embraced cooking and keeps the family supplied with a stream of unexciting but comforting homemade dishes.

Not much happens during Jayojit and Bonny’s two-month stay: trips to the bank, the market, walks in the neighborhood, polite conversations with family and acquaintances. Jayojit worries he is putting on weight. His mother worries her grandson isn’t eating enough. And, very slowly and indirectly, we learn more about Jayojit’s failed marriage. Unwilling to hazard a modern-style love match, Jayojit assumed that a compatible woman selected for him the old-fashioned way would be willing to settle down in an old-fashioned marriage. Yet his wife, although seemingly less Westernized than he, turned out to be much readier to ditch an unfulfilling relationship. In the immediate aftermath of the divorce, Jayojit would wake up alone in his house, “feeling quite separate from the man who’d written a book about economic development, who drove a Ford, who’d secured tenure.”

Yet for all his academic expertise in global markets, Jayojit has no idea how to advise his father about investing money. Intelligent, sensible and adaptable, he is the archetypal postmodern man who lacks a deep sense of identity. At the airport, he falls into conversation with a woman who asks him if he is Bengali. “Well--” he says, laughing, “well, I guess you could say--well, yes--I suppose I am!”

Indeed, what makes Jayojit so interesting is how unexceptional he is. The world he inhabits--divorce, computers, airports, endless mobility--is such a familiar place that most of us scarcely stop to take notice of it. Chaudhuri’s acutely observant portrayal renders its blurred outlines and shifting terrain freshly visible.

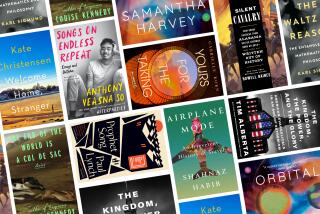

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.