Fake brides have their own agenda in Ukraine native’s heart-stopping ‘Endling’

- Share via

Book Review

Endling

By Maria Reva

Doubleday: 352 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Maria Reva creates beautiful, purposeful chaos. Informed by deep personal loss, her startling metafictional debut novel, “Endling,” is a forceful mashup of storytelling modes that call attention to its interplay of reality and fiction — a Ukrainian tragicomedy of errors colliding with social commentary about the Russian invasion.

A poorly planned crime serves as the anchor. “Endling” throws three strangers involved with Ukraine’s for-profit international matchmaking market together for a quixotic kidnapping caper in a nation on the brink of war. There’s a twisted, postmodern “Canterbury Tales”-like quality to these proceedings: Like medieval pilgrims, its central characters are each on a journey they hope will change their lives. And everyone is suffering some level of delusion.

Joe Mungo Reed’s second novel, ‘Hammer,’ is a slow burn of dangerous liaisons revolving around a Russian oligarch who comes to oppose Vladimir Putin.

If “Endling” has a main character, it’s the woman whose mission is to save the nation’s endangered snails; another key player is a lone wolf terrorist who hopes her political orchestrations will spark a family reunion. Then there’s the lonely, disaffected expatriate bachelor on the hunt for a quiet, traditional wife. Through their perspectives, black humor flows freely, as the motivations and experiences that brought this motley crew together rise to the surface.

Context is crucial in “Endling.” These characters cross paths early in 2022, when mass violence threatens to overwhelm every other concern. But despite the amassing of Russian troops on the border, the military invasion of Ukraine seems so surreal that no one knows what to believe or how much to fear. So these quests march on even as the crack of explosions grows louder.

The stories that emerge about our three key players are evocative, provocative and absurd — a contrast to looming darkness. Between those narratives, there are commentaries about the history and politics of Ukraine and on publishing and writing about Ukraine, plus the author’s family and its plight at the time of the book’s writing. As Reva, a native of Ukraine, writes in an early, epistolary section, in response to a magazine editor’s critique of the irreverence of her solicited essay about the war: “You’d asked for the type of reporting/response that would differ from that of a non-Ukrainian. In Ukraine, dark humor dates back to the Soviet days, giving people who live in uncontrollable circumstances a sense of power. If you can laugh about a dark reality, you rise above it, etc.”

No story better exemplifies that ethos than that of the teenage fake bride turned kidnapper who aches for her mother. Young, beautiful Nastia (a.k.a. Anastasia) — just 18 years old and six months past high school graduation — brings the group together. Ostensibly to stop the exploitation of women, this daughter of a fierce feminist activist who has long protested the tourist marriage market resolves to make an unforgettable public statement by kidnapping 100 male clients of the matchmaking service “Romeo and Yulia” at the start of one of its romance tours. Though the stunt is nominally aimed at exposing and ending degrading matchmaking practices, what Nastia really yearns for is her missing parent’s attention. When Nastia decides that a mobile trailer van in the guise of an escape room would be the perfect means of the men’s abduction, she begs Yeva, a fellow bride in possession of an RV, to rent it to her.

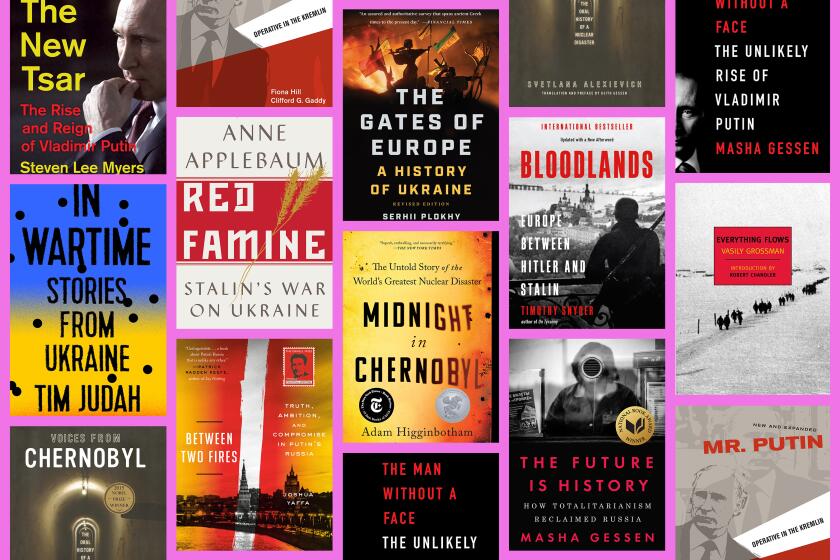

A primer on the past and present of two entangled nations at war, from histories of Chernobyl and famine to courageous chronicles of Putin’s terror.

Like Nastia, Yeva is a “bride” with an agenda. A scientist who’s lost her grant funding, Yeva uses the marriage mart grift to sustain her life’s work. Her story exemplifies the mercenary nature of the international marriage market. While Romeo and Yulia’s “brides,” as the women are called, aren’t paid a salary, they regularly receive gifts from suitors. In exchange for allowing the agency to use her as “shimmering bait” on the website, women like Yeva “could also return tour after tour and, without bending any rules, make decent money. In fact, the agency endorsed the practice: any gifts ordered by bachelors through the agency — gym membership, cooking class, customizable charm bracelet — could be redeemed by the brides for cash from the agency office.”

Yeva’s story gives the novel a melancholy moral center. And it’s from Yeva’s quest that the book derives its title: An “endling” is the last individual in a dying species, the kind she is dedicated to protecting. After losing access to institutional support, Yeva equipped the trailer as a roaming laboratory and storage site where (at the peak) she sustained over 270 species of rare gastropods. Though she prefers mollusks to men, it’s Yeva who insists on reducing the kidnapping target from 100 to 12, a number that the trailer could humanely accommodate.

Pasha, one of the men Nastia lures to the trailer, has his own ambitions. Born in Ukraine and raised in Canada, Pasha’s secret is that he doesn’t plan to return to the West with his bride like the other clients. Instead, he fantasizes about resettling in the Ukraine and forging a life that might command the respect he craves from his parents. Pasha is the sympathetic face of Western men beguiled by nostalgia for “traditional” wives unsullied by feminism and high expectations. His motives are sincere even if his relationship with women and his family might be better served through therapy.

“Endling” isn’t an easy read, but it is brilliant and heart-stopping. Authorial interludes can feel like interruptions, but by breaking the fourth wall, Reva forces us to pay attention to the ongoing devastation behind the narrative while unpacking the compromises of storytelling. Plus, Yeva, Nastia and Pasha and the merchants of romance spin their own fictions: They have trouble telling the difference between truth and make-believe even as the sounds of war grow near and even when bullets penetrate flesh.

This building up and breaking down of artifice forces reflection on how we use fiction to explore and bend reality while undermining the comforts of distance. As the author confesses, “I need to keep fact and fiction straight, but they keep blurring together.”

Bell is a critic and media researcher exploring culture, politics and identity in art.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.