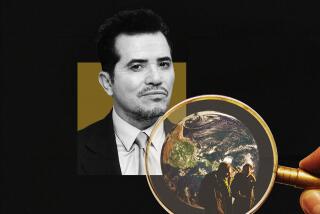

A Lie of the Mind

- Share via

“The first law for the historian is that he shall never dare utter an untruth,” Cicero said.

So a distinguished man comes apart over, of all things, a childish fantasy about soldiering in Vietnam.

Historian, scholar, popularizer, teacher: Joseph J. Ellis stood atop his profession. He won the National Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize for history. He commanded the bestseller lists with his telling of the turbulent birth of the United States.

In his latest work, “Founding Brothers,” Ellis’ concise rendering of men and moments brings to focus how it started: the left-right, liberal-conservative politics that define our country still.

It is a reassuring story. The passions and angers that sometimes overwhelm us have also helped us endure. It is an unsettling story. After 225 years, are we losing our idealism?

But Ellis’ book is more. “Founding Brothers” is an argument, a backlash to the view that the white male view of American history has been overdone.

Ellis acknowledges the trend of contemporary university historians who have looked elsewhere to fill in our story--to the women, the slaves, the natives whose perspectives were far different. His efforts, he explained, “constitute what I hope is a polite argument against the scholarly grain.”

To wit, the shape and character of our remarkable experiment in nationhood was “determined by a relatively small number of leaders . . . mostly male, all white.”

I side with Ellis on this. And it’s not just historians who look for the small and thereby fail to account for the large these days. Journalists, just for recent example, have told us more about Thomas Jefferson’s dalliance with a slave woman than his place in the pantheon of political thinkers. A reader of newspapers might recall the name of his mistress but not the shape of his mind. Ditto in the entertainment business. Pearl Harbor becomes a love story and an action sequence, not a turning point in a global struggle between social systems and peoples.

Ellis was a pathfinder among a contrary group of historians. With the skills of a scholar, the compression of a journalist, the story-telling powers of an entertainer, he broadened our vision by returning our attention to “the greatest generation of political talent in American history.” He reminded us of the noble calling of democracy.

Then he was unmasked.

He falsified his own C.V. Not the academic part, but his military service. He said he fought in Vietnam, and he didn’t. The Boston Globe revealed the facts. We are left scratching our heads at another of those human foibles that seems so unnecessary.

At Mount Holyoke College, where he is the Ford Foundation professor of history, administrators hurried to say that Ellis’ fiction about his own life does not diminish his scholarship.

No. It diminished all scholarship.

If the historian himself is a man of deception as well as achievement, what are we to think of his subjects? Certainly the figures of history are no less flawed than those who write it. So, what about Aaron Burr or Ben Franklin might be as fraudulent as Ellis’ Vietnam service and then passed on through the ages? Ellis’ sad example throws grains of salt on what he sought to illuminate--the exceptional character of the those who, by luck and wisdom and timing, altered the course of events.

Perhaps we’re wiser for this reminder that humans are, well, human. But it’s a short step from there to cynicism. Ellis’ double standard for the truth depreciates truth itself.

If students cannot believe in their professors, why believe in anyone? If book-buyers cannot trust the endorsement of the Pulitzer Prize, why trust anything? It’s just plain jarring--creepy, even--when a man who seeks to reconcile us with the purpose of our past cannot square himself with his own life history.

Today, we’ve grown so rampantly cynical that we’re afraid even to have heroes. Because, like Joseph Ellis, they can be revealed as something lesser at any time.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.