Still Making Waves

- Share via

CANNES, France — No international film festival is complete without a tempest in a teapot, and Cannes got one on Tuesday when French New Wave giant Jean-Luc Godard took some by-name shots at Steven Spielberg and American cultural hegemony in his new film and the press conference devoted to it.

Godard’s feature, “Eloge de l’amour,” is his first in competition here in more than a decade. Its world premiere called forth a huge crush, with critics lining up outside the screening room up to an hour in advance to be sure of getting in.

Complex and beautifully made, albeit with an unapologetically elliptical and fragmented style, Godard’s meditation on memory and history and who gets to own them not surprisingly divided viewers. The first walkout came within five minutes, but several people described themselves as in tears by the close.

Never one to shy away from politics, Godard has as one of his focuses the attempt, which he plainly mocks, of Spielberg’s representatives to buy the film rights to a love story that took place between a couple who fought in the French Resistance. “The real question,” the film’s press notes read, “is to know if an American superproduction today has the right to dramatize all the great hopes that came out of World War II.”

“Americans have no past,” one of Godard’s characters says, “so they buy the pasts of others.” The film also derides, albeit a bit pedantically, the way U.S. citizens insist on calling themselves Americans, and it pointedly describes the real Mrs. Schindler as living out her days in poverty despite the success of “Schindler’s List.”

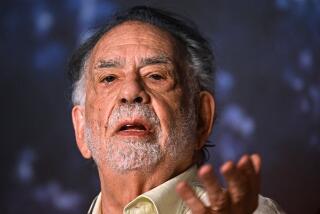

“I read about that in Le Monde, which is a reliable source,” the 70-year-old director explained at his packed press conference, smoking a small cigar and looking alternately irascible and bemused.

(Emilie Schindler, 93, lives in Argentina in a house purchased for her more than 30 years ago by Argentina B’nai B’rith, which still provides for her care.)

Asked about the Spielberg references, Godard said, “I have not met him, I don’t know him, but I’m not very fond of his films, and his name to me is very symbolic. To reconstruct Auschwitz the way he did, as an artist, an author, he did not have the right to do that, and it’s my duty to point a finger at him. He didn’t come up with an idea, he went looking for it elsewhere.”

Spielberg, through his representatives in Los Angeles, declined to respond to Godard’s remarks.

When an American journalist followed up and asked Godard how he expected “the people of the nameless culture between Mexico and Canada to react to your film,” the director responded dryly, “I don’t think there’s much of a chance they’ll be able to go and see it. Maybe some small theater might decide to show it.”

Witty both in person and on screen (“Eloge,” among other things, shows small children in native costume petitioning for “The Matrix” to be dubbed into Breton), Godard was more than amusing answering questions on numerous topics. For instance:

On the festivals he remembers: “When I first came here, in 1960 or ‘61, we saw a young man carrying reels of film to a projection booth. It turned out to be Jack Nicholson with a film of Monte Hellman’s. The Cannes of those days is gone.”

On whether today’s films have become too violent: “Yes, because it’s violence for the sake of violence, with no actual thinking behind it. We in the New Wave are partially responsible for this increase in violence, because our message was that the director was as important as the screenwriter.”

On a possible return to film criticism: “You don’t swim twice in the same waters. I’m afraid I might say nasty things, something I found easier to do when I was much younger.”

On attempted Hollywood remakes of his films: “It happens every time, but it never works. I once even lived on Mulholland Drive [the title of David Lynch’s competition film]. Even 20, 30 years ago, it never worked.”

Perhaps because one of the themes of “Eloge” is reconciliation, Godard did say something nice about Hollywood. Sort of.

“Film was intended to show things big, to show things in a different way, but filmmaking became very reassuring because California obtained a kind of stranglehold on it,” he said. “Still, if the choice is between a bad film from Kyrgyzstan or a bad film from Bruce Willis, I’ll choose a film of Bruce Willis, and I can’t tell you why.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.