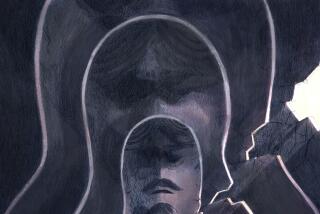

Portrait of a father who won’t give up

- Share via

As the father of two children who were born healthy and who, in the mystery of the phrase “God willing,” have remained so, I began to read respectfully and with foreboding attention the novel “Born Twice” by Giuseppe Pontiggia. It is a fictionalized memoir, though the fiction seems hard to find in a story with such idiosyncratic authenticity as a father’s coming to terms with his son’s birth condition, dystonic spastic quadriparesis, which causes him to lack control of his limbs.

Never mawkish or comforting, the story’s protagonist, Professor Frigerio, refreshingly avoids being a tower of strength or an exemplary figure. Pontiggia throws the reader into Frigerio’s lifelong unrelenting situation as father to a child who will always be different no matter how society changes or doesn’t change. The terrible truth begins from the first moment: “I can’t remember now who mentioned that the baby didn’t cry right away.... I remember the word: catatonic. The surgeon said it on his way out. The only question you want to ask is the one they don’t want to hear: what are the consequences?”

Despite the phony consolations of friends and relatives and the obscurantism of most doctors, Frigerio holds to the words of one doctor who foretold the situation of his son, Paolo: “The cerebral lesions, though not deep, have damaged his language and motor skills. The child will begin speaking late .... His motor skills will be imperfect. His intelligence will be intact yet he will seem immature because of his incomplete experience.”

Frigerio, recalling those words, wants to thank the doctor for what he said next: “These children are born twice. They have to learn to get by in a world that their first made difficult for them. Their second birth depends on you.... Because they are born twice, their journey through life is a far more agonizing one than most. Yet ultimately the rebirth will be yours too.”

“Born Twice” focuses narrowly on the experiences of Frigerio (the mother is off somewhere in the background), chronicling the endless physical therapy, the sure necessary expectation that the son is more than just his birth defect, the patient attention to teaching skills that come so naturally to other children but not to Paolo. He battles constantly with those who want to help but always on terms that never put Paolo at the center.

Because Frigerio is an observant teacher and is gifted with a real sense of language, Pontiggia allows him some victories against the so-called helping professionals. But the irony is ever present: What if your father is not so gifted, so articulate? The horror is too awful to contemplate, and the results are every day in our newspapers.

Pontiggia is really interested, however, in something far more suggestive and intangible than the conventional day-in, day-out portrayal of a father dealing with his son’s defect. At one point the author deftly turns from Paolo to his father, who is trying to help him with math. After an angry exchange with Paolo, who wants to give up, Frigerio says: “I don’t want to give up.... In life when there’s no alternative, we give up. A lot of people can’t wait for anything else. They live so that one day they can give up. There, I’m doing it again. I magnify other people’s shortcomings in order to minimize my own. Why don’t I give up? Is it because of me? ‘No,’ I say out loud, ‘it’s for him.’ He looks at me: I’m talking to myself. No, I think to myself, it’s for me.”

As in Pontiggia’s previous novel “The Invisible Player,” which concerned itself with a professor trying to identify an anonymous attacker and the paradox that nothing is less mysterious than the solution of a mystery, Pontiggia has taken the obvious in “Born Twice” and created a novel in which a father is allowed a second chance without sacrificing the dilemma and integrity of the child. “People who see him for the first time are not always satisfied with one glimpse,” Frigerio says. “They have to stop and turn around and look at him closer. He knows it when they do; I think he walks off with a pained expression. But maybe not, maybe he’s just being careful. He’s used to being watched. It’s me who’s relentless. It’s my face with the pained expression. That’s what unites us, from a distance.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.