Compelling Overview of Islamic World Covers Middle Ground Well

- Share via

Sometimes it seems that wars over Islam are as fierce in the bookstores as they are on the battlefield. Since the Sept. 11 attacks, books on Islam are hot--and so is debate over the nature of this faith. Current top sellers are sharply divided in their esteem of Islam, from Steven Emerson’s suspicious “American Jihad: The Terrorists Living Among Us,” to Karen Armstrong’s sympathetic “Islam: A Short History.”

Now comes a compelling contribution to the middle ground from the respected National Geographic Society. “The World of Islam” is a gorgeous melange of photographs, narratives and maps spanning nearly a century of reportage from the vast and exotic Islamic lands. Visually stunning and evocatively written, the book so thoroughly transports the reader to these ancient lands you can almost smell the camels, feel the blistering desert heat, hear the cacophony of voices raised in fervent prayer.

Yet as the articles chronicle the endless clashes over territory, ideology and faith, you are left with a sense of gloom that such agonizing history will keep repeating itself, preventing Islamic civilization from ever rising again to its once fabled heights.

One piece, for instance, spells out a dark prediction for Afghanistan’s future: “Today all Islam is in ominous ferment ... fights and disputes are still sweeping over Asia. Eventually and inevitably, Afghanistan must again become the object of rivalry among big powers that rub shoulders in the East.”

The year: 1921.

The book offers 27 articles on Islamic history, culture and faith, divided into four sections. The first, “First Impressions,” presents early Western chronicles of these then-little-known lands, including a 1914 peek into a Baghdad harem and a forbidden journey to a Shia pilgrimage site that ended with the non-Muslim writer being chased out of town.

The editors did not whitewash these earlier narratives by excising passages that would now be considered offensive and anachronistic. Followers of the faith are called “Mohammedans,” a term now discarded as pejorative; the harem women are described as “absolutely commonplace; some of them even stupid-looking.” Preserved in their original language, the essays offer as fascinating a glimpse into the evolution of Western reporting on Islam as they do into the faith itself.

The second section, “The Hinges of History,” chronicles the emergence of the modern Middle East as empires fell and new national boundaries were drawn in the tumultuous period of 1923 to 1960. Among other events, the articles look at the creation of Jordan, two years into the birth of Israel, and the extraordinary exchange of 2 million Turkish Christians to Greece and Greek Muslims to Turkey in the aftermath of World War I and the fall of the Turkish Ottoman Empire.

“Islam Rising” is explored in the third section, as the discovery of oil in the Mideast led to a massive transfer of wealth from industrialized nations to desert sheikdoms--some of which did not know what to do with it. One article poignantly chronicles an Abu Dhabi sheik who was gently pushed out of rule because he had no clue how to parlay the newfound wealth into better lives for his people and let stacks of paper bills be destroyed by insects. A firsthand account of the momentous hajj pilgrimage to Mecca reveals the enduring power of Islam.

And a 1987 essay on Saudi women, written from the inside by an American woman once married to a Saudi man, offers an alternative view to the common image of draconian sexist oppression. Compared to four decades ago, the author writes, Saudi women have made progress in acquiring education, professional jobs and the freedom to frolic publicly even at the beach--albeit all under the veil.

The final section, “Seeds of Conflict,” traverses the painful terrain of struggle that inflames so many Muslims today. In “Who Are the Palestinians?” veteran foreign correspondent Tad Szulc visits with them and Israelis and ends with the lament, “In that moment, the reality sinks in. This is a war between children, all scared of one another but determined to show their mettle.”

In the book’s final piece, veteran Afghan correspondent Ed Girardet writes of a 1989 encounter with a tall, bearded man who screamed at him, demanded to know why an infidel was in Afghanistan and threatened to kill him. The man’s name, Girardet later found out, was Osama bin Laden.

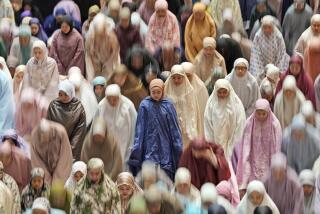

In keeping with National Geographic’s tradition of stunning photography, the book offers a range of portraits that capture the full humanity of Muslims. There is the dreamy young Iranian man making goo-goo eyes at his betrothed. The startling sight of a scantily clad female Saudi aerobics instructor. The fierce scowls of warriors bearing curved swords in older photos and Kalashnikov rifles in more recent ones. The sea of devout Muslims bowing in unison to Mecca, even on a train station platform.

Editor Don Belt is careful to include articles from Indonesia, the world’s most populous Muslim country, the Chinese hinterlands and the smoldering subcontinent of Pakistan, Kashmir and Afghanistan. Still, some may quibble that the collection predominantly focuses on the Middle East.

And this is not the book for those wishing an in-depth, comprehensive overview of Islamic history, philosophy, law, science, art and faith. For such seekers, “The Oxford History of Islam,” edited by Georgetown University professor John L. Esposito, has won wide acclaim.

“The World of Islam,” however, is a colorful, accessible and sweeping collection of works that succeeds in fulfilling National Geographic’s stated mission: to wage a “quiet war on ignorance” about a people and faith that we can no longer afford not to understand.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.