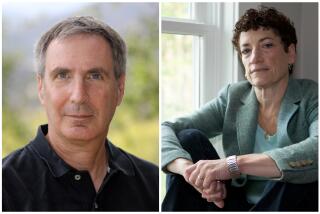

Robert Nozick, 63; Harvard Political Philosopher Pushed ‘Minimal State’

- Share via

Philosopher Robert Nozick, who dazzled liberal and conservative thinkers alike with his daringly original critique of the welfare state more than 25 years ago, died of complications from stomach cancer Wednesday in Cambridge, Mass. He was 63.

Once described as an academic bomb thrower for his ability to provoke intense discourse on fundamental questions, the Harvard professor was celebrated for his 1974 book “Anarchy, State and Utopia.” The work won a National Book Award and established Nozick as a major contemporary philosopher.

As a former liberal who embraced libertarianism, he brought impressive credentials to the debate over how far government should go. His imaginative grappling with issues of social justice and individual rights was conveyed in a style that most critics found elegant, accessible and frequently funny. “Capitalist acts between consenting adults” was an oft-quoted line from his audacious defense of laissez faire economics.

“Individuals have rights, and there are things no persons or group may do to them” without violating their rights,” he wrote. “ ... The fundamental question of political philosophy ... is whether there should be any state at all.”

Nozick built upon 17th century political theorist John Locke’s concept of a “state of nature,” in which no government exists and individuals live in perfect freedom with inalienable rights to life, liberty and property. Nozick advocated a “minimal state” that would exist only to provide basic safeguards against assault, theft, fraud and breach of contract.

Asserting that the modern state was a gross betrayal of this compact, he opposed such paternalistic laws as those preventing drug use or mandating the use of seat belts. He viewed taxation as a form of slavery and urged the demise of all government regulatory agencies conceived to coerce fair play.

He wrote his treatise in response to a Harvard colleague, John Rawls, who defended the redistribution of wealth in a best-selling 1971 book, “A Theory of Justice.” Rawls argued that individuals blessed with talent, money or other social advantage should benefit from their privileges “only on terms that improve the situation of those who have lost out.”

Nozick thought that was egalitarian nonsense. He argued that so long as individuals arrived at their advantages without making anyone “worse off,” they were morally entitled to enjoy them.

His arguments were so adroit that even critics in left-leaning publications sung his praise.

“Political philosophers have tended to assume without argument that justice demands an extensive redistribution of wealth in the direction of equality,” Peter Singer wrote in the New York Review of Books. “These assumptions may be correct, but after ‘Anarchy, State and Utopia,’ they will need to be defended and argued instead of being taken for granted.”

Although his father was a manufacturer, Nozick grew up in working-class neighborhoods around Brooklyn and attended public schools there. As a young man of 15 or 16, he unabashedly carried a copy of Plato’s “Republic” around the streets of Brooklyn. “I had read only some of it and understood less,” he once wrote, “but I was excited by it and knew it was something wonderful.”

He studied philosophy at Columbia, earning a bachelor’s degree in 1959. His master’s and doctorate were obtained at Princeton.

His political conversion occurred there. Already known as a philosophical genius, Nozick for the first time encountered someone whose arguments he couldn’t demolish: a libertarian capitalist. After some reflection, the committed socialist, who at Columbia had helped found a chapter of a group that became the radical Students for a Democratic Society, embraced an extreme form of libertarianism.

After studying in England on a Fulbright grant and briefly teaching at Princeton and Rockefeller University in New York, Nozick joined the philosophy department at Harvard in 1965. Four years later he became, at 30, one of the youngest philosophers granted tenure there.

“Anarchy, State and Utopia,” his first book, was published when he was 36. It was endorsed by W.V. Quine, a giant of American analytic philosophy, as “brilliant and important.” Among lay critics, the notices were just as glowing; Fortune magazine called him “perhaps the closest thing to a celebrity in the world of philosophy today.”

The book, which appeared a year before Margaret Thatcher rose to head Britain’s Conservative Party and six years before Ronald Reagan took the White House, made Nozick a darling of the New Right.

In later years he mourned the fact that he was most famous for his earliest work, even though he had moved on, in other well-received books, to much different philosophical terrain.

In a 1981 book, “Philosophical Explanations,” he dared to examine the perennial questions in philosophy, from the existence of free will to the meaning of life.

In “The Examined Life,” published in 1989, he offered a collection of 22 essays and short fiction on dying, love and other topics. The book raised some eyebrows for his second thoughts about some of his earlier stands.

The libertarianism he once championed now seemed, he wrote, “seriously inadequate.” He reconsidered the idea that enormous family wealth ought to be passed down through the generations, proposing instead taxes to ensure that the rich bequeath only the money they made.

“I used to think,” he once told an interviewer, “that the ideal philosophical argument was to produce words that set up a change in the listener’s brain, so that if he doesn’t accept the conclusion, he dies.... Why should [philosophers] be bludgeoning people like that? It’s not a nice way to behave.”

Nozick is survived by his wife, poet Gjertrud Schnackenberg, and two children.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.