Racism Unleashed

- Share via

In the course of a few terrible months in 1994, up to 1 million people were killed in Rwanda in a systematic slaughter not, as many newspapers reported at the time, as a result of chaotic and tribal civil war but as a deliberate government policy that was a carefully planned strategy, designed in advance and mobilizing thousands of unemployed youth into militias.

How could the world community allow such mass killing to happen? The opportunity for genocide was provided by a conjunction of circumstances allowing the hardliners to confuse the international community while they perpetrated the crime. All countries should have severed ties with Rwanda and expelled its ambassadors. But the organizers of genocide remained safe in the knowledge that outside interference would be at a minimum. No one gave the conspirators reason to pause.

The genocide in Rwanda was the first post-World War II extermination to be genuinely comparable to the Holocaust. It is one of the great scandals of the last century and, despite numerous inquiries and a growing body of literature, there are significant gaps in our knowledge about what happened.

“When Victims Become Killers, “ by Ugandan scholar Mahmood Mamdani, promises to explain the genocide through an understanding of citizenship and political identity in post-colonial Africa. But the book disappoints readers, failing even to expose one of the most central aspects, the growth of Hutu Power, the racist ideology that underpinned the genocide.

In Rwanda, there had been a history of state-sponsored and institutionalized racism against the minority Tutsis. Rwanda’s 7 million people were divided into three ethnic groups: the Hutus, roughly 85%; the Tutsis, 14%; and the Twa, 1%. The law required that all Rwandans be registered according to ethnic group, and the genocide of the Tutsis would become the centerpiece of state doctrine.

The genesis of the racist ideology that became known as Hutu Power was in northern Rwanda, in the regions of Gisenyi and Ruhengeri. The northern Hutus were fiercely independent and believed themselves to be distinct from the Hutus in the south. The northern kingdoms had been independent until the first decade of the 20th century, when the German military defeated them with Tutsi-led troops drawn from the south. In the north there was considerable bitterness. A detailed history of Hutu Power has yet to be written, but the name did not surface until 1992 in extremist circles at a time when the idea of a “big cleanup” took hold to solve the “Tutsi problem.”

Mamdani’s focus, however, is elsewhere. For him, the most troubling question is the genocide’s popularity. “My main objective in writing this book is to make the popular agency in the Rwandan genocide thinkable,” he writes. He is at pains to explain the large-scale civilian involvement in the killing. And he loses sight of the great influence of Hutu Power’s propaganda machine on the peasants. The effectiveness of Hutu Power radio, with its catchy nationalistic theme tunes and racist jingles, must never be underestimated. The broadcasts of Radio-Television Libre des Mille Collines (“the free radio of a thousand hills,” the name for Rwanda) played an integral role in the plot.

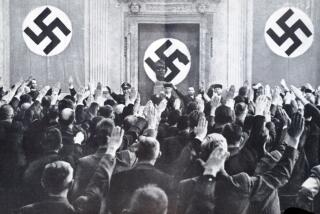

In genocide it is necessary to promote a racist ideology and define the victims as being outside human existence to legitimize any act, no matter how horrendous. We may never know when the Hutu Power conspirators first conceived of the plan, when the northern oligarchs, threatened by democracy and power-sharing, decided to use genocide as a political weapon. By the time it began, the youth militia had grown to 30,000 and there were about 85 tons of weapons and agricultural tools distributed all over the country.

Mamdani concludes that neither greed nor hatred persuaded the people of Rwanda to kill. Nor was it unquestioning obedience. It was fear: fear of a return to servitude and a conviction that they, the Hutu masses, were the victims of yesterday, and that the Tutsis, their former rulers in pre-colonial and colonial days, would turn them into victims once more.

Mamdani gives the impression that the genocide was an extremist manifestation of civil war. This denies the genocide its status, and Hutu Power cannot be described as just another extremist political tendency. The conspirators who unleashed the terror have yet to see their day in court, and only then will the world finally learn the details of their genocidal plotting.

Raphael Lemkin, the father of the 1948 Genocide Convention, believed that genocide could be predicted and prevented. Lemkin had argued that genocide was most likely to occur where there was racism and that the more extreme the racism, the more likely a genocide would take place. Lemkin believed that genocide was ever present and that it “followed humanity like a dark shadow, from antiquity to the present time.”

Mamdani does not mention Lemkin in the brief history of genocide included in “When Victims Become Killers,” but he does cite the genocide of the Herero people in German South West Africa in 1904. The German military, faced with continuing armed resistance, had prepared to exterminate as many Herero as possible. Those people left alive were put in concentration camps, where a German geneticist, Eugen Fischer, did medical experiments on race.

One of his prominent students in later years was Josef Mengele, who carried out experiments at Auschwitz. Mamdani argues that modern genocide was nurtured in the colonies, and although the genocidal impulse to eliminate an enemy may indeed be as old as organized power, he believes it was European “race branding” that made it possible to exterminate an enemy with an easy conscience.

The race idea, Mamdani argues, was conceived in Europe. Europe was also the land of its prehistory and its culmination. Mamdani suggests that the idea that Tutsis and Hutus were different races had come with the European colonizers. It was the colonizer who thought up the idea that the Tutsis had “invaded” a country that “belonged” to the Hutus. The Hutu extremists used this version of history during the genocide, portraying Tutsis as “aliens.”

Mamdani describes how the horror of colonialism led to two types of genocidal impulse: the genocide of the native by the settler and the native impulse to eliminate the settler. The genocide in Rwanda, he argues, needs to be understood as a natives’ genocide, but he does not even speculate on the possibility that genocide may have already been a feature of pre-colonial Africa. After all, the prime symbol of Tutsi power is the Kalinga drum, which was said to be a reminder of Hutu inferiority, for it was decorated with the penises of defeated Hutu kings, signifying the rivals’ complete defeat, surely a powerful genocidal symbol.

In Rwanda in 1994, a plan to eliminate the Tutsis was methodically and thoroughly pursued. Only by understanding how and why this happened can there ever be any hope for the future. “When Victims Become Killers,” however, helps little in that process.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.