The Scientist Manque

- Share via

Just about everyone knows Jules Verne, if not through his novels then from the movies made from them: “Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea” (1954) and “Around the World in Eighty Days” (1956). There were also movies made of “From the Earth to the Moon” (1958), “Journey to the Center of the Earth” (1959) and “The Mysterious Island” (1961), but these were considerably less popular, and Verne was lucky that his reputation did not have to depend on them. In his day (he was born in 1828 and died in 1905), Verne was considered a serious author, whose subject matter often incorporated recent scientific advances.

When he wrote “Twenty Thousand Leagues” in 1870, the submarine had just been introduced as a weapon of war, and underwater breathing devices were in their infancy. Reading Verne’s novels as they appeared must have been as exhilarating an experience as watching men land on the moon in 1969. But when hasty or sloppy translations turned the work of a major French novelist into boys’ adventure stories, not unlike those of Edgar Rice Burroughs or H. Rider Haggard, the English-speaking world was deprived of some of the best adventure novels ever written.

In addition to his better-known works, Verne wrote a series of novels that were (in his lifetime) classified as “voyages extraordinaires” and included “Five Weeks in a Balloon,” “Around the World in Eighty Days,” “From the Earth to the Moon” and “The Invasion of the Sea,” which sounds like another bathysphere novel but is instead about how the sea can be made to invade the Sahara Desert. Written in 1905 and based on fact (the French really did want to flood part of the eastern Sahara and turn it into an inland sea), “The Invasion of the Sea” now appears for the first time in English with an introduction by Verne scholar Arthur B. Evans.

Like all of Verne’s adventure stories, it is filled with scientific detail that lends verisimilitude to the narrative (if you want to know how to build a canal to flood a desert, this is the manual for you), but “The Invasion of the Sea” is also a rollicking tale of brave French soldiers and engineers, accompanied by their loyal servants (think of Conseil in “Twenty Thousand Leagues” or Passepartout in “Around the World”), who face searing heat, sandstorms, quicksand and, of course, treacherous Tuaregs. The villains of the novel are the poor nomads who object to having their ancestral homeland flooded, but their dastardly nature--the “fearsome natives” are described as “thieves by nature and pirates by instinct”--is so characteristic of the lower orders of humankind that one is happy to see the otherwise empty desert turned into another French Riviera. Verne accepted unquestioned the “white man’s burden,” which was to subjugate and improve those who had the misfortune to live in “uncivilized” parts of the world. Desert dwellers obviously needed water (whether they wanted it or not), which could be provided only by clever French engineers.

Verne’s novels were popular because they were often rousing adventure stories with a heavy infusion of science or at least scientific terminology. We might compare him today to Michael Crichton, who also has a gift for storytelling and a knack for weaving science into his novels. But just using “science” doesn’t automatically validate his work, nor does it elevate it to a higher plane of literature. Verne often gets the science wrong. In the beginning of “Twenty Thousand Leagues,” he has Professor Arronax declaim that the animal that has been sinking all those ships was a giant narwhal or sea unicorn that “often attains a length of 60 feet.” In fact, it wasn’t any sort of animal at all but rather Captain Nemo’s Nautilus, and narwhals don’t get larger than 16 feet and, despite the ivory tusk that projects from their mouths, are perfectly harmless.

But Verne was writing fiction, and there is no rule that says you have to stick to the facts. Just because 60-foot-long narwhals or submarine-attacking, man-eating giant squids do not exist, doesn’t mean that an author can’t use them in a work of fiction. (Was there ever a ship-attacking white whale? Or a 25-foot-long white shark that vindictively attacked everybody in sight?) Weaving science into his adventure novels made them that much more popular, and Verne’s readers probably wanted to believe everything he told them. The introduction to “The Invasion of the Sea” contains detailed notes about how the French planned to go about flooding the Sahara, rather as Ferdinand de Lesseps dug the Panama Canal, which is to say not very successfully.

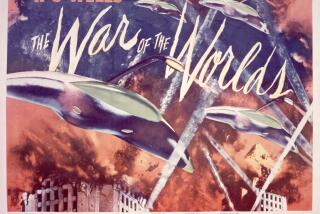

In 2002, a new edition of “The Mysterious Island” was issued by the Modern Library, translated by Jordan Stump and with an introduction by Caleb Carr. This novel, originally published in 1875, is a sequel to “Twenty Thousand Leagues” because Captain Nemo reappears, but Arronax, Conseil and Ned Land have been replaced by five escapees from a Confederate prison camp in Richmond, Va., who manage to ride in a balloon--how Verne loved balloons!--all the way across North America before landing on the mysterious South Pacific island of the title. (We know it is near Australia, because they encounter kangaroos, a koala and an echidna, a sort of spiny marsupial anteater, which they boil up for a tasty stew). They undergo a succession of life-threatening adventures (an attack by a troop of orangutans, an invasion of escaped convicts, the dog-eating dugong) but their pluck and fortitude, not to mention the indomitable Captain Nemo, see them through.

Verne was almost preternaturally productive. In addition to his novels, short stories and essays, he wrote books of geography and history, including a historical geography of France and the three-volume “Celebrated Travels and Travelers,” which included “The Exploration of the World,” “Great Navigators of the Eighteenth Century” and “Great Explorers and Navigators of the Nineteenth Century.” Anyone who questioned the science or history in his novels could always refer to his historical interpretations. These histories are minutely detailed and, as far as I can tell, fairly accurate. But the novels that I’ve read, with their hair’s-breadth escapes, man-eating cephalopods, loyal servants, trusty dogs and depraved, conniving natives (or pirates, convicts, Berbers or whatever), still suggest Boy’s Life adventure tales to me. I’m missing the intellectual subtleties of the new translations, but when I think of “Twenty Thousand Leagues,” I still think of the giant squid attacking James Mason aboard the Nautilus or Kirk Douglas playing the guitar to a sea lion. Verne’s stories are, in short, fun.

Although he predicted many things in his novels--including balloon travel, the helicopter, the electrical engine and interplanetary travel--it is, I think, safe to say that Verne, a man given to “scientific” extrapolation, could never have envisioned the Internet. Instead of the barrage of information now available to us, Verne had newspapers--it was said that he read 15 every day--and he was a compulsive taker of notes.

Imagine how this scientist manque would have delighted in the computer revolution, which has brought us among other delights a Web site devoted to him (www.jv.gilead.org.il). The site contains the full text of 17 of his 60 novels (in French, English and Spanish), frequently asked questions about Verne, a critical analysis of his work, an Internet mailing list, the Jules Verne virtual library, a chronology of Verne’s life, the complete Verne bibliography, the Verne virtual bookstore, links to the Societe Jules Verne and pictures of all 70 Jules Verne stamps, issued not only by France but also by Hungary, Nicaragua, Upper Volta, Cameroon, Grenada, Mali, Guinea, Togo, the Cook Islands, Israel and Cuba. The old man would have loved it.

*

From ‘The Mysterious Island’

It was nearly eight o’clock when Cyrus Smith and Harbert set foot on the upper crest of the mountain, at the very summit of the cone.

The darkness was now complete, limiting visibility to no more than two miles. Did the sea surround this unknown land, or was it joined in the west to some continent of the Pacific? They still could not say. A band of clouds lay over the western horizon, heightening the darkness of the night, and the eye could not determine whether the meeting of heaven and water was as straight and unbroken there as on all other sides of the island.

But on that horizon there now appeared a vague gleam, slowly descending as the cloud climbed toward the zenith.

It was the slender crescent of the moon, soon to disappear from view. But the meager light it cast afforded a clear glimpse of the horizon beneath the rising cloud, and the engineer could see its quivering form briefly reflected on the surface of the water.

Cyrus Smith grasped the boy’s hand, and, in a somber voice:

“An island!” he said, just as the lunar crescent sank beneath the waves.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.