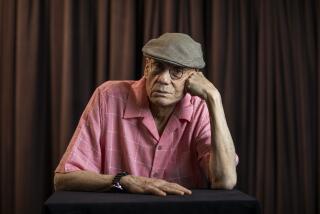

Steve Earle Hooks Into the Beat

- Share via

The road makes sense to Steve Earle. He’s spent time there as a traveling musician, and he has been drawn to the romance of escape since his first comical attempts at riding the rails of Texas at age 13. “I don’t believe in cruise control,” the singer-songwriter declared Tuesday at the Knitting Factory, reading from a poem that name-dropped Jack Kerouac and celebrated old-school driving skills.

Earle was there to headline the fourth day of the club’s Beat Fest, an appreciation of the lasting cultural impact of the writers and artists of the Beat Generation. The night also included veteran rock rebel Simon Stokes, who painted vivid, demented imagery with the help of a six-man band led by guitarist Wayne Kramer. And Wanda Coleman offered intense readings of several poems dedicated to “all those who still have the spirit of the rebel angels.”

Stokes and Coleman have an obvious connection with the Beat legacy. But it was Earle who underlined the impact of that history with unlikely force. For more than two hours he stood alone on stage, mingling his best songs with tales of personal misadventure before joyfully reading an excerpt from Kerouac’s “On the Road” during his encore.

He began the show by joking, “I used to be a folk singer; now I’m a recovering folk singer.” But despite time served in the Nashville establishment, Earle has always been a folk singer. Which made Tuesday’s performance a lot more Woody than Hank, opening with Bob Dylan’s 1962 take on Eric Von Schmidt’s “Baby, Let Me Follow You Down.”

In the same way that Dylan was inspired by the rootless introspection of the Beats, Earle crafted songs of biting emotional depth, blending humor and hurt, along with the occasional moment of social commentary. Either strumming broad strokes or picking delicate patterns on his acoustic guitar, Earle played material that spanned his career, singing gravely of lost love and death row.

He dived into the brutal work of Lightnin’ Hopkins with an edgy reading of “Limousine Blues.” But whether he was assaying ancient blues or his own recent work, Earle sang as the restless traveler, often in a voice suggesting a man beaten down by broken dreams, but still able to feel the pain.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.