History 101 Lite

- Share via

“In human history, almost nothing is preordained.”

These closing words of Geoffrey Blainey’s “A Short History of the World” seem to have guided him in compiling its 31 chapters. Each chapter is an essay in itself, often slenderly connected to its fellows, and many chapters mingle familiar and unfamiliar information about different peoples in different parts of the world. The result is a sometimes interesting, sometimes disappointing miscellany about the human past.

Any attempt at writing world history obviously must somehow select from overabundant data. Blainey explains his approach, as follows: “I was conscious from an early stage of the danger of making the book too compressed, of trying to pack in too much. I began to realize that I was leading the readers on a long journey, parts of which had to be made with speed--otherwise the destination would never be reached. On the other hand the journey occasionally had to be slowed down so that readers could look about them and savor a scene or milestone in the history of the human race.

“By design,” he continues, “the book therefore is a mixture of fast movement and short periods of rest and meditation. Some of these pauses I wrote in advance.... Among such episodes are the European man who died about 5,000 years ago and was recently found in Alpine ice, still clothed and remarkably preserved; the way of life of the early Maoris of New Zealand; the influence of the Indian indigo plant on the color blue; the brides sacrificed in the rushing waters of the Yellow River in ancient China; Abraham Lincoln preparing to give his famous speech at Gettysburg; the strange death of the composer Tchaikovsky in tsarist Russia; the signing of the peace on the deck of an American battleship in Tokyo harbor in 1945.”

This list illustrates the range of Blainey’s interests and sensibilities and suggests the cabinet of curiosities with which he decorates his chapters. I for one did not know, for example, that Cardinal John Henry Newman wrote “Lead, kindly Light” after surviving a nasty Mediterranean storm; that Isaac Newton died at a ripe old age with all but one of his teeth and without needing to use spectacles; or that the Burmese drew petroleum for household lighting from shallow wells decades before 1859, when drilling in Pennsylvania inaugurated the modern oil industry.

Blainey is an Australian and, in an earlier book, “The Tyranny of Distance” (1966), he analyzed the influence of geographical isolation on Australian history. He remains acutely aware of geography in “A Short History of the World,” and he pays special attention to the diffusion of domesticated plants and animals, as well as diseases, together with human migration: All are factors of key importance for Australia’s history.

Blainey’s Down Under viewpoint also induces him to treat the history of Southeast Asia, Australasia and the Pacific Islands more fully than others usually do. Even so, he betrays occasional carelessness, giving two dates for the introduction of rice into Japan; claiming that maize “originated independently both in South America and in Mexico”; and saying that cotton found its way to India from Mexico, where it was cultivated as early as 6000 BC in one passage and later declaring that it was probably first cultivated (some 3,000 years subsequently) in India.

An attractive feature of Blainey’s book is his sensitivity to the sensory experience of pre-industrial, pre-urban populations. He devotes two persuasive chapters to this theme. In Chapter 4, “The Dome of Night,” he samples the portentous meanings attached to lightning, shooting stars, meteorites, stars, dreams and calendrical calculations by a miscellany of diverse peoples; and in Chapter 31, “No Fruits, No Birds,” he explains how artificial light and modern transport have conspired to diminish the sovereignty of the seasons, to blur night and day. They’ve caused the moon and stars to fade from everyday urban consciousness.

But when treating standard themes of ancient and medieval history, Blainey sometimes wobbles. Aegina was not the first place to mint coins; Pericles was not elected sole general of Athens for 15 years in a row; Hinduism did not arrive in India “with Indo-European migrants”; ancient Rome was not governed by “representative assemblies”; neither canal locks nor windmills were first invented in medieval Europe; and so on.

Such perhaps trivial errors of fact are enhanced by occasional observations that seem silly. Confucius, for example, “was a scholar of a kind more likely to be found in Athens than perhaps in any other state along the Mediterranean.” Or Blainey writes: “In 1206, however, Genghis Khan, the chieftain of the Mongols, miraculously united these riders of the steppes.” Or again: “The tragedy was that Western civilization, when at last it ceased to believe in witches, was also ceasing to believe in humankind’s immense capacity for evil as well as good.”

More generally, Blainey preserves strong traces of the Christian and British viewpoints that shape his mind. He devotes four pages to Jesus’ life and death, for example, while Buddha gets one page and Confucius is dismissed in a paragraph. Three chapters deal with Christianity; Islam gets one; and other world religions receive only casual mention. Similarly, Britishers and Americans play a preponderant role in his history of the last two or three centuries.

This is perhaps attractive for the Australian and, now, American readers he addresses in “A Short History of the World.” But it is not a good way to prepare for navigating the 21st century, as it tends to reinforce religious and national self-centeredness while relegating the overwhelming majority of humankind to marginality that they are sure to resent and may be about to alter.

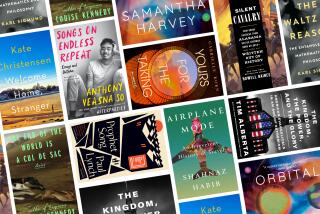

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.