2 Americans Share Economics Prize for Contrarian Work

- Share via

WASHINGTON — Two American academics won the Nobel Prize in economics Wednesday for applying psychology and experimental research to such conundrums as why stock markets form “bubbles” and why people think they can sell an item for more money than they will pay to buy it.

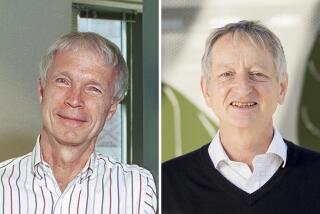

Daniel Kahneman, 68, a psychology professor at Princeton University, and Vernon L. Smith, 75, a professor of economics and law at George Mason University in Virginia, will share the $1.1 million that goes with the prize, awarded annually by the Swedish Academy of Sciences.

For the record:

12:00 a.m. Oct. 12, 2002 For The Record

Los Angeles Times Saturday October 12, 2002 Home Edition Main News Part A Page 2 National Desk 9 inches; 344 words Type of Material: Correction

Nobel--A story in Section A on Thursday about the Nobel Prizes should have reported that the prize in economics was established in 1968, not 1969. Also, economics prize winner Daniel Kahneman earned his undergraduate degree from Hebrew University in Jerusalem, not the University of Tel Aviv. And in some editions, the death of Alfred Nobel, who established the prizes in his will, was incorrectly reported as occurring in 1986. He died in 1896.

“He is more than deserving of it,” said Caltech economist Charles R. Plott of the award to Smith. “His work was a key step in transforming economics into a laboratory, experimental science.”

“It’s extremely well-merited,” said Brookings Institution economist Henry Aaron of the award to Kahneman. “Unlike a great many creative people, not only is Danny Kahneman smart, he’s a very sweet man.”

Economists have long thought both men were in line for a Nobel Prize. Asked Wednesday what it felt like to be chosen for one, Smith quipped: “Well, I’m glad my friends were finally right.”

Each man’s work represents a distinct challenge to classical economic theory, in which individuals always act rationally and there always is a single price on which buyers and sellers can agree.

Kahneman’s work, together with that of his longtime collaborator, the late Amos Tversky, focuses primarily on individuals and seeks to ferret out peculiarities in the way people make economic decisions.

In a demonstration inspired by their writings, University of Chicago economist Richard Thaler gave one group coffee mugs and a second group money, then offered to buy mugs from the first and sell mugs to the second.

Classical theory would predict that students selling the mugs would ask for about the same price as the buyers would be willing to pay. But, in fact, the sellers asked for twice as much.

“The willingness to accept payment is always greater than the willingness to pay,” Aaron said.

That might seem obvious to lay people. But such systematic divergences from classical theory are important when it comes to financial decisions. Kahneman and Tversky found that people make such decisions on the basis of hunches, shortcuts and rules of thumb, rather than a careful calculation of risks and rewards.

Smith’s work focuses on markets more than individuals and poses a double-barreled challenge to classical economics.

His method involves constructing controlled experiments to see how people behave, rather than advancing theories about how a whole nation’s economy functions. He is widely known as “the father of experimental economics.”

His experiments have led Smith to conclude that most markets for goods, services and labor can operate with far fewer controls and even fewer people than is generally supposed. But a few markets, especially financial ones, are nearly impossible to stabilize.

“I can show you bubbles and crashes in the lab, but it’s not clear what we can do about them,” he said in an interview.

Smith’s experiments have been used by companies such as IBM Corp. and Hewlett-Packard Co. to test changes in corporate policy before instituting them. They have been employed by agencies such as the Federal Communications Commission to organize spectrum auctions.

Smith said he now is out to show that electricity can be successfully traded, California’s recent disastrous experience not- withstanding.

Kahneman was born in Tel Aviv in 1934 and has dual citizenship in the U.S. and Israel. He has an undergraduate degree from the University of Tel Aviv in psychology and mathematics and earned a doctorate in psychology at UC Berkeley. He has been at Princeton since 1993.

At a news conference Wednesday, Kahneman singled out his old friend Tversky.

Speaking of the Nobel Prize, he said: “Such an award seldom reflects the contributions of a single individual. This is particularly true in my case, since the award is given largely for work that I did many years ago with my close friend and colleague Amos Tversky who died in 1996.

“The thought of his missing this day saddens me,” he said.

Smith was born in Wichita, Kan., in 1927, received a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering from Caltech in Pasadena and a doctorate in economics from Harvard. He spent years at the University of Arizona before being lured to George Mason last year with six colleagues.

Awards for achievements in physics, chemistry, medicine, peace and literature were established by Alfred Nobel, the Swedish inventor of dynamite, in 1896. The economics prize was added by the Swedish central bank in 1969.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.