Jury Urges Execution for Stayner

- Share via

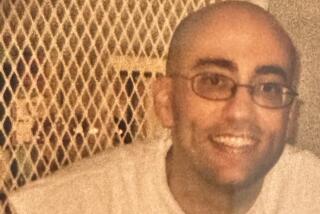

SAN JOSE — A jury declared Wednesday that Yosemite murderer Cary Stayner should be executed for the slaying of three women tourists, killings that rattled the serenity of the Sierra woods in 1999.

The jury pushed aside arguments that Stayner, 41, should be spared a trip to death row because of dogged mental health problems and a loveless childhood rife with dysfunction and family tragedy.

Stayner faces a Dec. 12 sentencing before Santa Clara County Superior Court Judge Thomas Hastings in the murders of Carole Sund, 42, of Eureka, her 15-year-old daughter, Juli, and Silvina Pelosso, 16, a family friend visiting from Argentina.

Jurors avoided eye contact with Stayner as they stepped into a packed courtroom after less than six hours of deliberations over two days. As the verdict was read, Stayner sat motionless and the courtroom remained hushed.

His attorney, Marcia Morrissey, said afterward that she would request a new Superior Court trial in addition to the appeal automatically filed in capital punishment cases. Morrissey, who jousted repeatedly with Hastings throughout the trial, had hoped even more evidence of Stayner’s troubled past might be presented.

“This fight won’t be over for Cary Stayner until he gets a fair trial,” Morrissey said. “Obviously I’m very disappointed.”

But the family of Carole and Juli Sund countered that a mountain of evidence had been presented--and a just verdict reached.

“Condemning Cary Stayner to death is not happy for anybody,” said Carole Carrington, whose daughter and granddaughter died at Stayner’s hands. “But it’s justice.”

The Sunds and Pelosso vanished in February 1999 from the Cedar Lodge in El Portal, a tiny community in a deep river gorge outside Yosemite National Park.

One of the biggest searches in state history ended four weeks later and a county away when the torched hulk of their rental car was discovered on a forest logging road with the charred remains of two victims in the trunk.

Note Led to Body

An anonymous note--Stayner later admitted to sending it, even asking someone else to lick the stamp--led authorities within days to the shore of a nearby lake, where they found the nude body of Juli Sund, her neck sliced open.

Initially, the FBI focused on a group of methamphetamine addicts in Modesto, and by summer felt solid enough about the case to publicly announce that it was safe again to return to the woods.

But five months after the tourists disappeared, Joie Ruth Armstrong, 26, became Stayner’s fourth victim. Her beheaded body was found near the Yosemite nature guide’s cabin in a remote corner of the park in July 1999.

Within days of the gruesome killing, authorities caught up with Stayner. He pleaded guilty in federal court to Armstrong’s murder to avoid the death penalty.

State prosecutors refused to budge in the killing of the tourists, a case tried in a state Superior Court because it occurred outside the national park. The trial was moved from Mariposa County to San Jose because of pretrial publicity in the Sierra foothills.

George Williamson, the lead prosecutor, described Stayner as a methodical killer who carefully hatched a plan to hunt down young women like prey, sexually assault them and kill them.

Stayner, he noted, even left wet towels in the motel room to make it look as if the three women had showered and left, hardly the moves of a mind clouded by mental illness.

In a taped confession played at the trial, Stayner admitted that he used the ruse of a leaking pipe to get into the motel room of his victims. He strangled Carole Sund and Pelosso, then took Juli Sund on a winding journey that ended on the shore of Lake Don Pedro.

Stayner confessed to FBI agents that he carried the high school cheerleader from the car like a “groom carried a bride across the threshold,” then sexually assaulted her. Stayner told Sund that the gun he wielded at Cedar Lodge never was loaded. Then he slit her throat.

The 12-week trial played out in three parts, with the jury in August finding Stayner guilty and in September declaring that he was sane during the killings. The penalty phase stretched over 12 days, as jurors weighed whether Stayner should die by lethal injection or live out the remainder of his life in prison.

From the trial’s first day, defense lawyers conceded that Stayner killed the three women. But they said he suffered mental health problems that should keep him off San Quentin’s death row.

Asking Jury for Mercy

Morrissey, the defense attorney, noted that Stayner had shown remorse and pleaded with jurors to “overcome the cruelty of Cary Stayner’s acts with understanding, mercy and love.”

Morrissey said a lethal mix of mental health issues--obsessive-compulsive disorder, depression and sexual dysfunction--boiled over in 1999. Visions and voices Stayner experienced for years--ranging from Nazi death camps to beheadings--took over, she said. The man who had been a passive and kind presence for 37 years turned into a killer.

During the penalty phase, the defense called on more than 50 character witnesses: Stayner’s parents, sisters, former girlfriends, classmates and co-workers. All portrayed him as the antithesis of the coldblooded killer.

Blown-up photographs showed a gaptoothed boy with freckled face. Stayner, friends said, was the kid who sat at the end of the bench in Little League, the high school cartoonist caught up in his own little world, the teenager who didn’t retaliate when other kids picked on him. He refused to hunt, one relative recalled, rationalizing that the birds had never done anything to harm him.

But the Stayner family was deeply troubled, a clan that considered the display of emotions taboo, friends said. Their lives were torn asunder when Stayner’s younger brother, Steven, was abducted in 1972 at the age of 7 by a pedophile and held hostage for seven years before escaping with another young boy. Their return out of the mists of time caused a national media stir in the family’s hometown of Merced, culminating in a book and TV miniseries.

During his brother’s absence, Cary Stayner and his three sisters were virtually ignored, the parents testified. Delbert Stayner, the father, said he mostly just yelled at Cary. The children endured family vacations devoted to following up one crackpot tip after another about Steven’s alleged whereabouts.

When the brother returned, life didn’t improve much for Cary, relatives said. Affection was showered on Steven, but the others were still ignored. Later, Steven Stayner died in a motorcycle accident, sending Cary spinning into depression.

Psychiatrists who examined Stayner said he had experienced vivid imagery of sex and violence since an early age. His family tree, they said, is laden with relatives suffering from mental illnesses, including depression and pedophilia.

As a child, Stayner pulled out his own hair. In grade school, he was molested by an uncle, the jury was told.

As an adult, Stayner had a fixation with Bigfoot and the apocalyptic prophesies of the 16th century astrologer Nostradamus. Though he was tall, burly and handsome, friends said he rarely dated or even flirted. One former girlfriend testified their romantic life had been troubled by his sexual difficulties.

Defense experts contended during the trial that Stayner’s brain may have been damaged in the womb, probably in a region that controls emotional impulses, an assertion that a prosecution expert discounted as unfounded.

Described as a Predator

Prosecutors said Stayner was a predator, not a man driven by mental health problems. During final arguments, Williamson told jurors there was no compelling evidence demonstrating that at the time of the murders Stayner was “mentally or emotionally screwed up.” He questioned whether Stayner’s life, though troubled, was “so tragic that he’s deserving of your sympathy and forgiveness.”

To drive the point home about Stayner’s deeds, the prosecutor displayed photos of Armstrong’s headless body and played Stayner’s confession of the murder’s brutal details. Stayner, Williamson also noted, slept soundly the night after he killed the three sightseers.

While incarcerated after the killings, Stayner was asked by an FBI agent to write a letter to the families of his victims. Instead, he penned a note to Juli Sund that was read to the jury.

He expressed his sorrow to the teenager, and talked of the years she would miss. He said she was in a good place, and that he would be going somewhere far worse.

“I know right from wrong, and I don’t think that I am insane,” the letter concluded, “but there is a craziness that lurks in my head, thoughts I have tried to subdue as long as I can remember. I’m just sorry that you were there when the years of fantasizing my darkest dreams became a reality in the flesh.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.