For Armstrong, Familiarity Breeds Respect in France

- Share via

Paris — A small boy, no more than 4 years old, held a French flag in his right hand, an American flag in his left. He was pressed close to a metal barrier on Avenue de la Bourdonnais on Saturday as, one by one, the cyclists whizzed by.

Fans could catch only a glimpse of the men, blurs of color leaving a breeze in their wake, and the small boy snuggled close to his father. But when the 198th rider came up the street, almost at the finish, father and son smiled and shouted “Lance!”

Without a common language to communicate, the man pointed to his heart, then toward Lance Armstrong. The little boy mimicked the gesture.

As the Tour de France began with a 4.03-mile prologue, a sprint that began at the Eiffel Tower and ended at the Champ de Mars, it’s clear that not all the French are rooting against Armstrong, the cocky American who has dominated the world’s most prestigious cycling road race.

The 31-year-old from Plano, Texas, is trying to become the first American and the second man to win the Tour de France five consecutive years, and become only the fifth man to win as many as five titles. And as Armstrong tries to make history in a race a Frenchman hasn’t won in two decades, it would seem understandable for the French to root hard against him.

Just about anything American is unpopular in France after the U.S.-led war in Iraq, and Armstrong, after all, is just about as red, white and blue as an athlete gets. Indeed, those are the colors he wears as a member of the United States Postal Service team, and he comes from the same state as President Bush.

Armstrong has survived cancer and then, after he won the Tour de France in 1999, two years of French-led investigations into whether he was using illegal, performance-enhancing drugs.

The investigations turned up nothing. And now, it seems the unpredictable French may be ready to embrace Armstrong in his quest for cycling history.

“Maybe we didn’t like him for a while,” said Alain Villiard, a 24-year-old amateur cyclist from Paris. “Of course we wish for a Frenchman to win this race and not an American. But I think we should admit right now that Armstrong is a great cyclist and if he wins again, we must applaud him no matter his nationality. He deserves it.”

Chris Carmichael, longtime friend and trainer for Armstrong, said, “I think Lance has earned the respect of the French fans. It’s not for me to say anyone deserves respect. But I can say that Lance has earned the trust and the admiration of racing fans everywhere.”

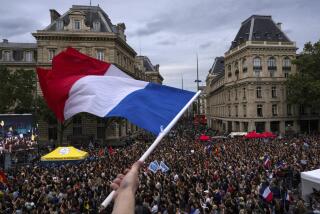

The festive crowds that came out to cheer all the cyclists Saturday seemed to save a special noise for Armstrong, who finished seventh, about seven seconds behind winner Bradley McGee of Australia in the first stage of the grueling three-week race.

This is the 100th anniversary of the first Tour de France and were it not for his nationality, Armstrong probably would be among the most popular athletes ever, said Villiard, who had stopped for a rest at the Eiffel Tower on Thursday after tracing the route of Saturday’s race.

With the courage he showed in overcoming testicular cancer in 1996, with the way he has shown sportsmanship during the race, with the strength he has ridden through the mountains and the dedication he has shown to understanding what mental and physical qualities it takes to win a three-week torture test, Villiard said, “I know that Lance Armstrong should be so popular here.

“But please,” Villiard said, waving his arms toward the Eiffel Tower, “understand that sometimes it is so frustrating when Americans win everything.”

Although the French soccer team is loved above all else sporting in this country and although tennis’ French Open offers the most glitz and glamour, it is the Tour that best captures this quirky, querulous place.

This year’s version began and will end at the Eiffel Tower. But it also travels more than 2,100 miles through big cities and small towns, through the Alps in the east and the Pyrenees in the west, up and down and around a country that considers itself the most beautiful in the world.

There is no charge for admission. Fans by the thousands line the sides of small, rural roads and busy highways reaching out to wish the riders well, standing close enough to smell the bodies and to be drenched in the sweat of the racers.

It is this very closeness, this connection between fan and athlete, even an athlete such as Armstrong who travels with bodyguards, that has made the Tour so special and also caused some private concern among some of Armstrong’s USPS teammates.

“The world is a difficult place,” said Dan Osipow, a USPS team leader. “We’ve heard catcalls and such through the years, yes. But, say, a Russian baseball team had come to the U.S. and won a World Series and then went on a barnstorming tour of the U.S.

“In most of the big cities throughout the country, the Russian team would be appreciated. But if the Russian team showed up in some small towns, there might be people who’d yell, ‘Go home.’ Same with us. We’ve been everywhere. We’ve heard everything. There will always be detractors. But there will always be many more people who appreciate Lance.”

Since March, Armstrong, who has considered himself a friend of President Bush but who also publicly expressed opposition to the war, has tried to end speculation about any fears he might have had.

Before winning the Dauphine Libere, the final Tour de France prep race last month, Armstrong said that competing “was much more of a concern six or eight weeks ago. I prefer not to mix sport with politics and I hope the French people along the road realize that as well.”

In an interview Saturday on French television, Interior Minister Nicolas Sarkozy said almost 24,000 police would be employed during the three-week race and that Armstrong had no need to worry.

“Lance Armstrong will be protected,” Sarkozy said. “There is no reason for things to go badly. We are friends of the Americans, the Americans are our friends. Lance Armstrong has won the Tour de France four times. He may win a fifth. There’s no reason to mix him into international debates or politics.”

Sarkozy also mentioned Armstrong’s recovery from cancer and said, “If we don’t support him, who should we support?”

For much of the two years after he won the first of his four consecutive Tours, Armstrong had a somewhat adversarialrelationship with the French public and its media.

After Armstrong became the surprise winner of the 1999 Tour and the world learned about his recovery from life-threatening cancer (13 tumors that had spread from his testicles to his lungs and brain had been surgically removed), he was greeted here more with suspicion than admiration.

Led by respected national newspaper Le Monde, Armstrong faced a barrage of questions in almost every news conference about whether he used illegal performance-enhancing substances.

Armstrong didn’t help his case with his association with Michele Ferrari, a doctor currently on trial in Italy, accused of administering banned substances to cyclists. Armstrong has said he taps into only Ferrari’s insights about diet and training at altitude.

And even though Armstrong has never failed a drug test, it wasn’t until last September that the French investigation cleared Armstrong and the USPS team of any use of performance-enhancing drugs.

Jean-Pierre Bidet, a cycling expert for the French daily sports paper L’Equipe, said it is more than Armstrong’s heritage that prompted the thorough investigation involving drugs and the coolness of French fans.

“French people love the tension and excitement of a close competition,” Bidet said. “But in the way Lance crushes the opponent, the way he starts so strong and hard from the beginning, there is now the feeling of boredom. For many of the fans, it seems as if the race is over before it starts.”

Indeed, Armstrong won his fourth Tour last year by more than seven minutes. The final week was more ceremonial victory tour than a race.

Nothing is ever certain, though.

“You can never take anything for granted,” Armstrong said. “I wish I could come into these races and have everybody say, ‘He can’t win.’ That tends to work better. When everybody talks about my victory, it gives me a bad feeling.... Anybody can win.”

But, if he does win, Armstrong told U.S. reporters in a conference call last week, he has no intention of quitting, despite suggestions on some cycling Web sites that seeking to become the first six-time winner of the Tour might be “disrespectful to past champions.”

“I intend on racing next year, 100%, win or lose this year. If I get through this year and am fortunate enough to win, and if I have the same fire and passion going into next season, I’m going for it. That’s for sure.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.