Playing Through

- Share via

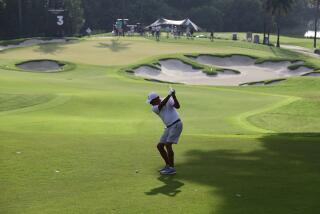

DOHA, Qatar — The Doha Golf Club seems like an oasis, a swath of green across otherwise starched desert at the edge of the Persian Gulf. Out on the course, amid rustling palms, it is easy to forget about the rest of the world.

So Kevin Na has done his best to think only of golf.

The 19-year-old from Diamond Bar has paid scant attention to fighter jets and military cargo planes growling overhead. He hasn’t watched much news on television.

Most of all, he has ignored Iraq’s being only a few hundred miles north, a proximity that prompted dozens of veterans on the PGA European Tour to withdraw from the $1.5-million Qatar Masters tournament, which ends today.Struggling to make it as a professional golfer, Na jumped at the chance.

“They’re not going to start fighting until Monday, right?” he said, relaxing outside the clubhouse. “I’ll be out of here by then.”

Informed that conflict could erupt at any time, Na abruptly sat forward, eyebrows raised from behind wraparound sunglasses.

“Really?” he asked. “It could?”

Here in the Middle East, rumors of war are encroaching on the normally insular world of sport. Athletes and organizers find themselves drawn into a historically uncomfortable quandary: In troubled times, should the games go on?

Concerned about player safety, FIFA has postponed the World Youth Soccer Championship, scheduled for later this month in the United Arab Emirates.

The Dubai World Cup -- the richest day in horse racing -- will go on as planned March 29, but at least one prominent United States trainer, Bobby Frankel, has decided not to send his horse, Medaglia d’Oro.

For Americans, fears reverberate beyond the Gulf.

NFL executives are watching carefully as they approach the start of the NFL Europe season in April. Cyclist Lance Armstrong has wondered about trying for a fifth consecutive Tour de France title in July.

“As an American abroad, it’s scary to think of being over there in a big public event with a war going on,” he told The Times last month.

Beyond matters of safety, there is the question of appropriateness.

“It might be difficult for people to justify going to a sporting event and having fun while, at the same time, soldiers are hunkered down in the desert preparing to fight,” said Peter Roby, director of the Center for the Study of Sport in Society at Northeastern University.

Pete Rozelle, the late NFL commissioner, openly regretted not canceling games the weekend after President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in 1963. The Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks sparked arguments over when to resume play.

“It’s a tough decision,” Roby said. “All kinds of things have to be taken into consideration.”

The current debate heated up in early March at another golf tournament, the Dubai Desert Classic, when Tiger Woods withdrew.

His competitors initially dismissed it as a special circumstance. “He’s a little more high-profile and probably a little more worried,” American golfer Stephen Sokol said.

As the days passed, however, the mood shifted. Rumors began circulating on the driving range. Players would hear that war had begun and hurry to the clubhouse to check the television, Scottish golfer Simon Dunn said.

A week later, and hundreds of miles closer to Iraq, the Qatar Masters seemed a riskier proposition.

In fact, life in this tiny nation, a thumb of land jutting into the gulf, seems relatively normal. People congregate in the streets at night to enjoy a cultural festival. Superstar tenor Luciano Pavarotti performed here last week.

Even high-ranking American military officers have ventured from their compound on the outskirts of Doha -- war would be directed from here -- to visit the golf club. Gen. Tommy Franks, chief of the U.S. Central Command, recently played an early morning round, course executives said.

Still, there are worries about what could happen. During the Persian Gulf War in 1991, Scud missiles landed in Qatar, and residents now wonder if the prevailing northerly winds might blow poisonous gas into their country.

British golfer Greg Owen spoke out in favor of canceling the tournament.

“Is it worth risking a lot?” he asked. “I have a baby girl and I want to see her grow up. A golf tournament is not the be-all and end-all.”

There is precedent for halting play. The Olympics went on hiatus during the World Wars. Baseball suspended its games on D-day.

College and professional leagues temporarily shut down after Sept. 11.

But the decision becomes trickier when left to athletes, said Andrew Parker, director of the Warwick Centre for the Study of Sport in Society in Coventry, England.

“There is no certain protocol or procedure,” he said. “We’re asking them to make a moral decision on an individual level, and some athletes don’t seem to want that responsibility.”

In Boston, Roby sees at least one argument for continuing with events like the Qatar Masters.

“With this war, we’ve been talking about it for several months and it’s not like a shock that throws people off their equilibrium,” he said. “I guess the way you should approach it is: The reason our troops are over there getting ready to fight is so we have the right to live our lives in ways we see fit.”

Tournament organizers agreed. The decision was especially personal for Chris Myers, the club’s general manager, who in 1990 worked at a hotel in Kuwait and was taken hostage for five months by Iraqi invaders.

“If I thought it was time to go,” he said of the current situation, “I’d be the first one on the plane.”

Myers hired extra security, smartly uniformed officers visible throughout his club.

There has been talk of providing a chartered jet or ground transportation to whisk players south to Dubai should war break out.

Ian Woosnam decided to play at Doha. So did Padraig Harrington, the 10th-ranked golfer in the world, though he acknowledged that, coming from Ireland, political turmoil and violence are nothing new to him.

“As somebody said, it’s more dangerous at Heathrow Airport [in London] and that’s probably the truth,” he said. Then he added, “Hopefully I’m not too blase about it.”

Other players did not feel as comfortable, especially after the British and German governments issued advisories against “non-essential” visits to Qatar. Darren Clarke, Nick Faldo and Seve Ballesteros were among the 50 who withdrew.

“A lot of the guys, their wives said, ‘I don’t want you to go,’ ” veteran British player Roger Chapman said. “So they didn’t.”

Sokol, a 23-year-old from Connecticut, heard the same thing from his mother but could not pass up his first invitation to a European tour event.

“Obviously you watch the news and you get more and more worried,” he said. “The opportunity just outweighed any fears I might have had.”

The pleasant atmosphere in Doha came as a surprise.

“From what CNN tells you, you expect bombs going off and troops running down the 10th fairway,” he said.

But the proximity of a potential war is not lost on the golfers. Before the tournament, Chapman and several others were playing a practice round when a military helicopter thundered past.

“You look up,” he said. “You think, ‘What’s going on?’ ”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.