The man who redrew the world

- Share via

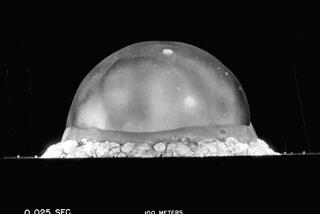

At Cold War’s end, we entered a new century to find a self-proclaimed unipower astride the globe. We seem quickly to have acknowledged the basic maxim of most geographers: All the world’s places are connected. But who rules? Who decides? After a century of total war, we have learned one lesson: There are no final victories. The world map gets redrawn: There are fluid frontiers, porous borders, shifting alliances. Today, as a U.S. president is poised on the brink of wars without end, concerned citizens must wonder: How did it come to this? Where will we go from here?

Neil Smith’s vividly written, brilliantly researched “American Empire” is profoundly illuminating for these dangerous, crescendo times. His 20-year immersion into private papers, government documents and various sources has resulted in a portrait of Isaiah Bowman (1878-1950), a leading American geographer, advisor to presidents and president of the Johns Hopkins University. The book is also, Smith writes, “a history of geography, but even more a geography of history.”

Because Bowman helped design the maps that heralded America’s rise to globalism, and because Smith writes with verve and audacity about politicians and visionaries from World War I through the Cold War, “American Empire” changes the substance of our perceptions -- especially regarding the goals of Woodrow Wilson, Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Harry Truman.

Smith’s two most stunning contributions concern Bowman’s influence on the geography of rescue during World War II (which developed out of his disdain for Jews and horror of communists and political refugees) and the evolution of geography into geopolitics and economics (from empire as territorial conquest to business investment). As a leading geographer, Bowman went from a discoverer of old worlds to a creator of a new empire.

World War I obliterated antique regimes: The Hohenzollern, Hapsburg, Ottoman and Romanov empires were history. New nations were created along lines of confused ethnicity and damaged shards of the rival past. A buffer of troubled states arose to strangle Russian and German ambitions. After 1919, new geopolitical realities emerged; everything changed. Smith describes the tensions, the “fiesta of egos and intrigue” within Wilson’s think tank known as the Inquiry and in America’s leadership class, from a fresh geographic perspective.

As director of the American Geographical Society and as geographic advisor and bridge between the War Department and the National Research Council, Bowman was disinterested in the more liberal aspects of negotiation -- native rights, the prohibition of forced labor, minorities treaties -- and preferred “forced assimilation and ethnic dilution.” The importance of the “war to end all wars” was the separation between economic expansion and direct military control of territories. The new geography promised permanent peace and fulfilled Wilson’s 1912 campaign slogan to “broaden our borders and make conquest of the markets of the world,” thus motivating Bowman’s future work. But it was immediately suspended by geography’s old realities: Germany’s territorial reduction and anguish, Russia’s upheavals and the Allied intervention against the new Communist regime.

Bowman fought valiantly for the covenant of the League of Nations, which he believed was the hope of the new world order. But the Senate rejected the League, and the U.S. entered an isolationist phase incomprehensible to Bowman. He spent the inter-war years on the board of the Council of Foreign Relations, working to craft a new political geography devoted to U.S. interests and world development. Smith’s chapter on the council and the future of economic and political power brilliantly illumines the trajectory of America’s half-century.

But Smith’s most astonishing chapters are those on Bowman’s work as president of Johns Hopkins University from 1935 to 1949 and as FDR’s geographer. Bowman was hailed as a democratic life-enhancer with a “planetary consciousness” when he was named Johns Hopkins’ fifth president. But the limits of Bowman’s democratic liberalism were stark: He had no use for much of the New Deal, disparaged the unemployed and uninformed, despised Jews and minorities, scorned his own faculty. Leading faculty members retired or decamped, horrified by his attitudes. Bowman unceremoniously fired a young historian, the now esteemed Eric Goldman, because he was Jewish -- unleashing a student and faculty protest. “There are already too many Jews at Hopkins,” Bowman bluntly told the history chairman. In 1942 he imposed a Jewish quota for students because, he said, “Jews don’t come to Hopkins to make the world better ... [but] to make money and marry non-Jewish women.” He opposed opening the university to students of color, despite several attempts by faculty members. Above all, Bowman worried about the genetic future, warning of America’s decline “unless we improve our human breed.... To support the genetically unfit and also allow them to breed is to degrade our society.”

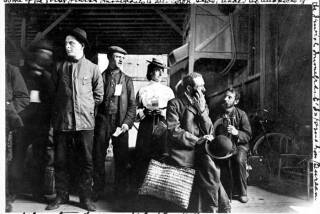

Curiously, FDR appointed Bowman to direct his studies of rescue and refugee resettlement. Attracted by Bowman’s work on frontiers, FDR was also grateful for Johns Hopkins University’s role in military research and preparation. Between 1938 and 1942, Bowman and his team scouted the Earth to find usable spaces along “pioneer fringes” for resettlement. This assignment revealed Bowman’s prejudices. When the Refugee Economic Corp. purchased 50,000 acres in Costa Rica, hope emerged. But progress ended when Bowman suggested that our Latin American allies were needed for larger purposes. All urgency was replaced by delay.

But in 1939 FDR announced publicly that 10 million to 20 million refugees would be rendered homeless by war, and financier Bernard Baruch offered to fund a study of postwar reconstruction and resettlement. FDR urged Bowman to meet with Baruch and direct the program. This resulted in 93 reports but did nothing for refugees. Between 1940 and 1942 little was done. Then came word of widespread extermination and flight, and the super-secret “M Project” (for Migration) emerged. From 1942 until Truman ended funding in 1945, the M Project yielded 650 documents and much other memoranda. Reported by Smith in full for the first time, the daily reality of Bowman’s efforts makes for harrowing but essential reading.

Ultimately, the M Project was a limited, troubling decoy: Mass slaughter initiated no sense of urgency for rescue or resettlement. Bowman had presided over “a scholarly investigation of land settlement.” Concerning Palestine, the conclusion was: There were too many Arabs, and it was out of the question. According to Smith, Bowman’s report was both bigoted and prescient: In 1944 the population of Palestine was 1.7 million, of which 61% were Muslim and 30% were Jewish. Unless Palestinian Arabs agreed, a Zionist state would result in endless warfare. Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt challenged Bowman, who insisted that supporting such a state would come “at great cost in blood and money.”

Bowman spoke most bluntly to Arthur Hays Sulzberger of the New York Times, warning that 90 million Arabs would mobilize against a Zionist state. This “is a ghastly alternative.” He compared it with German Lebensraum: “Is it not putting power behind a nationalist program in such a way as to take land occupied by one people and give it to another?” Nevertheless, FDR announced in October 1944 that he favored a Jewish homeland in Palestine. Regarding North America, Bowman argued for Jewish exclusion, because of growing U.S. “prejudices.” Elsewhere he considered resettlement only if refugees possessed significant capital. His basic conclusion was that refugees should be spread as thinly and quietly as possible “all over the world.”

Bowman’s influence on FDR’s legacy is complex. Though horrific regarding refugees, it became basic economic policy at the Bretton Woods Conference in 1944 and during the deliberations concerning the United Nations at Yalta and San Francisco. The International Monetary Fund and the World Bank were globalism’s contribution to Wilson’s post-colonial vision of empire. Bowman, present at each step of the creation, was again presiding over the world’s re-mapping. Bowman’s geographers and other allies systematically considered a postwar world beyond “chaos and hunger,” provided that the U.S. was in control. The details are crisply and spectacularly presented by Smith, especially the long argument between FDR and Churchill over colonies and between FDR and Stalin over the structure of the U.N.

To the bitter end, as Smith concludes, the facts presented are powerful and relevant to our world. Bowman was for many an arrogant, best forgotten, much-despised man who presided over the destruction of geography as a discipline and ruined much else that he had built. But his legacy survives in our ongoing effort to modify the geopolitical world he helped craft. For one brief moment, after the Soviets crumbled, the first President Bush remembered the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, passed by the U.N. in 1948, and ushered the long-neglected bright hope for humanity through the Senate in 1992. Little has been written about that and how it was quickly eclipsed by renewed warfare and heightened terror. Now the world proceeds to dicker with its future through bombs and occupation -- the old, pre-Bowman way. A “contested global geography” goes on. Ultimately, it will be an empire -- with or without walls -- or a wasteland, or a world neighborhood, with security, justice, fair market prices for all. Citizens of all persuasions will want to read this book for its many profound alternatives to occupation and conquest. *

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.