The worlds of Pocahontas

- Share via

Pocahontas

Medicine Woman, Spy, Entrepreneur, Diplomat

Paula Gunn Allen

HarperSanFrancisco: 350 pp., $26.95

*

IN her new book, “Pocahontas,” Paula Gunn Allen tries to convey the spirit world of Native Americans by inviting the reader to inhabit it with her.

A retired professor of English and American Indian Studies at UCLA and author of “The Sacred Hoop,” Allen is no outsider, viewing Native Americans’ imagination and world view as a detached observer. The great-granddaughter of a Laguna Pueblo woman of New Mexico, she enters into it fully.

Borrowing concepts and terms from the late theoretical physicist David Bohm, Allen divides reality into “implicate” and “explicate” orders, or implied and explicit realities. In the explicate order, she writes in this new, thoroughly Native American look at the woman so famous in Colonial history, “events, people, objects, even planets and galaxies, take on the guise human brains recognize and consciously interact with,” she says. “A rock ... is a rock ... a mineral [is] constructed of measurable, definable molecules that hold to a definite pattern of organization.”

In Algonquin terms -- Pocahontas was an Algonquin -- there exists also the implicate order, a “subreality of energies before they take on shape or form as we recognize them,” she writes, a dimension analogous to a world “that can be both force and being, wave-form or particle, identity or surmise.”

Moderns reject this implicate world, which they regard as primitive (though Allen doesn’t use that word). Indians, she insists, are able to hold in balance the two conceptions at once. It is from this starting point that she reconstructs the familiar story of Pocahontas.

This is it in brief: Capt. John Smith, one of the English settlers who sailed to Virginia in 1607 and founded Jamestown, was captured by Indians serving Chief Powhatan. Smith was stretched on the ground and about to be executed by braining with stones when the maiden Pocahontas threw herself on Smith’s back and successfully pleaded for his life.

She later gave crucial aid to Smith and the Colonists, who subsequently captured and baptized her Rebecca. After Smith returned in England, she married John Rolfe, founder of Virginia’s tobacco industry, and went with him to England, where she was received by court society and where she died.

Upon this simple story Allen constructs her edifice of supposition and imagination. “While I am constrained and guided by Western conventions for biography,” she writes, “I have made every attempt to ‘nativize’ this work by structuring it to conform as much as possible to the narrative conventions of the American Indian Oral Traditions” and to place Pocahontas in the Algonquin Indian context in which she lived.

Allen says Pocahontas was not the daughter of Powhatan as Smith believed, but was indeed a princess as well as the “medicine woman, spy, entrepreneur and diplomat” of the subtitle. In doing the traditional work of highborn Native American women in a matriarchal society, Allen says, Pocahontas manipulated the encounter with the English as much as possible to her tribe’s advantage.

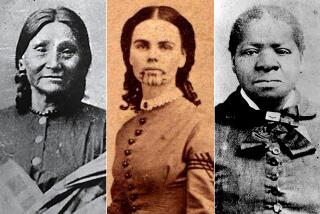

Allen finds striking comparisons between Pocahontas and two other fabled Indian women, Malinalli -- or Malinche, Cortes’ lover and mother of his son -- and Sacagawea, guide for Lewis and Clark’s expedition of the West. “Each occupied a leadership position among her own people,” Allen says, “and each acted as an agent of change, bridging worlds so that eventually harmony might ensue.”

She also asserts that Indian prophecies had foretold that the time of Pocahontas was to be the beginning of a time of renewal for the world -- “The Great Transformation” believed only now to be coming to an end.

Allen tells her tale in the circular Native American way, with many digressions and stops along the way to look at her story from several points of view, in keeping with tradition.

“Pocahontas, like her people, can never be known in terms of ‘facts,’ bereft of the spiritual tradition that defined her and her people, or understood outside the spirit-centered world they inhabited,” Allen writes. “A biography of Pocahontas must tell her life in terms of the myths, the spirits, the supernaturals and the world view that informed her actions and character.”

Allen’s effort commands respect, if not unquestioning assent at the dawn of the 21st century.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.