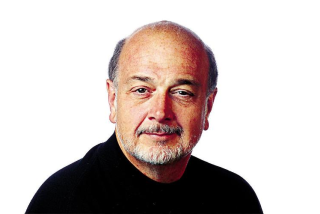

Sidney James, 97; Guided Sports Illustrated From Obscurity to Success

- Share via

Sidney James, whose stewardship of Sports Illustrated as its founding editor saved the then-struggling magazine from a premature demise, has died. He was 97.

James died Thursday at a nursing home in Alameda of cardiopulmonary arrest and prostate cancer.

Sports Illustrated, a staple of every professional sports clubhouse and a centerpiece of coffee tables across America, would not have moved into the nation’s consciousness were it not for James’ persistence and unflagging optimism.

Selected personally by Henry Luce to head the general-interest sports magazine, James shielded the publication, titled “Project X” upon its launch in 1953, from critics who contended that it could not attract a viable audience and would serve only to drain the considerable resources of media giant Time Inc.

“James midwifed his magazine through such journalistic shot and shell, it’s a wonder it ever got out of the hangar,” Los Angeles Times columnist Jim Murray, a former colleague at Sports Illustrated, wrote in 1994.

“James never let a discouraging word or a negative thought creep into the procedure. He was the most indefatigably optimistic editor I’ve ever met. Whenever one of us would show up for work that fateful summer of ‘53, shaken and uncertain, reeling from overnight votes of no confidence from our own colleagues, James would remind us that they called the invention of the steamboat ‘Fulton’s Folly.’ ”

The magazine did not turn a profit until 1964 and by then James had become publisher. Now in its 50th year and with a circulation of 3.15 million, Sports Illustrated is widely considered a powerhouse of American journalism. Over the years, the magazine with a literary bent has featured such acclaimed writers as John Steinbeck, William Faulkner, Red Smith and George Plimpton.

Sports Illustrated under James wasn’t always a commercial or critical success. The inaugural issue, dated Aug. 16, 1954, ran a feature titled “You Should Know: If You Are Going to Buy a Puppy.” Not exactly the kind of hard-hitting news one would expect to find in today’s magazine.

“The magazine wouldn’t decide under James what the most important sports to cover were,” said Michael MacCambridge, author of “The Franchise: A History of Sports Illustrated Magazine.” “It hadn’t made a distinction between spectator sports and participatory sports.

“But without his enthusiasm, the magazine would have had a great deal of trouble surviving to find itself. He was somebody who, at a time when the magazine was losing money and a lot of people were saying it was on its deathbed, had this Mister Magoo-type optimism and kept marching forward.”

As James himself put it years later, Sports Illustrated “wouldn’t be a sports magazine, it would be the [sports magazine] with the best color, the best writing, the best everything.”

The magazine was topical and went beyond the nuts-and-bolts coverage provided by most newspaper sports sections. Sports Illustrated exposed the shady dealings of boxing promoter Jim Norris, leading to his expulsion from the sport, and suggested comprehensive rules changes in football later adopted by the Big Ten Conference.

Born in St. Louis, James briefly attended Washington University in his hometown before going to work for a local newspaper, where his father had reviewed theater.

He liked to tell the story of reporting for duty and being told to go see the city editor. Immediately surmising that the editor was a menace to the newsroom, James went home and waited six months until that editor left before returning for work.

James joined Time magazine in 1936 and managed Time Inc.’s West Coast editorial operations during World War II.

James’ accomplishments transcended his work with Sports Illustrated. While an assistant managing editor at Life, James was responsible for the magazine’s publication of Ernest Hemingway’s “The Old Man and the Sea” before its release as a novel.

“He was a much better reporter than a writer,” recalled Otto Fuerbringer, 93, a former managing editor at Time who had known James since they worked together at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch in the 1930s. “He discovered personalities, he discovered trends. Wherever he was, he was all over the lot covering everything.”

James spent six years as managing editor of Sports Illustrated and served as publisher for four years. After retiring from Time Inc., James was chairman of WETA, the public broadcasting station in Washington, D.C. He was instrumental in arranging the public television broadcasts of the Watergate hearings.

Years earlier, James had directed the first televised broadcasts of the Democratic and Republican national conventions in 1948 in Philadelphia. In 1979, he won the George Foster Peabody Broadcasting Award.

James, who lived in Laguna Hills for more than 25 years, had been in declining health over the last year, necessitating the move to a nursing home in Alameda near his son Christopher. James had been mostly confined to home since a car accident in 1991 forced him to give up golf and prevented him from using the electric typewriter he preferred to a computer. His first wife, Agnes, died the same year. His wife, Donna, died last July.

“He was a sunny personality despite the difficulties,” his son Timothy said. “He was a guy who could cope with almost anything. He always saw the positive side of things.”

In addition to Timothy of New York City and Christopher, James is survived by a daughter, Sidney Kistin of Corrales, N.M.; eight grandchildren; and two great-grandchildren. Services are pending.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.