A library for Little Rock

- Share via

Little Rock, Ark. — The William J. Clinton Presidential Center, which opened Thursday a few blocks east of this capital city’s quiet downtown, has plenty to recommend it architecturally. The main section of the library complex, by Polshek Partnership Architects of New York, is a sleekly contemporary glass box, three stories high, that cantilevers out toward the Arkansas River. Its form is derived from the half-dozen bridges that are among Little Rock’s best-known landmarks -- as well as by a certain bridge metaphor that the president was fond of repeating. Sunlight pours through the open, airy interiors, even reaching the full-size replica of the Oval Office on the third floor. The architects included a number of green-design features, including solar panels on the roof and radiant heating beneath bamboo floors.

Most significant, Clinton and the leaders of his library foundation made a farsighted choice for the 30-acre site of the $165-million, 165,000-square-foot project, building it in a languishing industrial section of town, crossed by old train tracks, on the south bank of the river. The library has begun to act as a catalyst for nearby construction, including a forthcoming $13.9-million headquarters for Heifer International, a nonprofit that funds anti-poverty programs.

What the building lacks, though, is some of the charisma -- the voracious, imperfect vitality -- that made Clinton himself such a maddeningly fascinating president. Many of its spaces, covered in aluminum panels, stone or cherry wood, have an ever-so-staid, even corporate feel. Its missteps are not the result of reaching too far but simply of having failed to resolve a few tricky design problems.

There’s no requirement, of course, that a presidential library match, or even evoke, the personality of its main client. It has a number of other constituents to answer to, from locals to tourists to visiting scholars, most of whom will expect a building that is museum (or archive) first and architectural landmark second. Nobody wants a Clinton library in the shape of a saxophone, or with a gift shop selling pork rinds, Gap dresses and books on urban empowerment zones on the same shelf.

Architectural radicalism wouldn’t have made sense either -- not for a president who so relentlessly charted a course to the political middle. Still, a little Clinton-style impulsiveness might have done the place some good: The architecture is, on the whole, more crisply sensible and not nearly as daring, or even as satisfying, as a first glance at its bold silhouette might suggest.

In that sense, the library has something in common with the Polshek firm’s most acclaimed project to date, the Rose Center for Earth and Space at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. Finished in 2000, the Rose Center suspends a spherical planetarium inside a 95-foot-high glass cube and is modeled after Etienne-Louis Boullee’s 18th century, unbuilt monument to Newton; it’s also said to be among Clinton’s favorite buildings.

Like the new library, the Rose Center looks fantastic at night, glowing like a lantern. (If you had to come up with a ranking of architectural excellence based solely on the appearance of buildings seen from 100 yards away an hour after sunset, it would be pretty close to the top of the list.) But once you get a closer view of either building, walking through it, examining its details and palette of materials and how it works at human scale, the appeal fades -- not completely, but enough to leave a nagging sense of disappointment.

The library joins 11 others around the country -- every former president since FDR has one, as does Herbert Hoover -- in an odd architectural club. Presidential libraries are planned and built as private ventures. Once they’re finished, they’re handed over to the government and operated by the National Archives (with the exception of the Nixon library in Yorba Linda, which is privately run). The architectural heavyweights of the library group include John F. Kennedy’s, designed by I.M. Pei and finished in 1979 on a site overlooking Boston Harbor, and Lyndon B. Johnson’s, a 1971 concrete building in Austin, Texas, by Gordon Bunshaft of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill that is unfailingly described as “monolithic.” Clinton’s library is the biggest and most expensive of the bunch. It holds an avalanche worth of what’s been dubbed Clintoniana -- 80 million documents, for starters, and 79,000 artifacts, including more than 18,000 gifts.

Its architecture is best appreciated from the circular drive at the foot of the main building, where an arc of white-painted bollards offer a reminder that Little Rock is now home to a world-class security risk. The site dips as it gets closer to the river; to keep the main volume level, the architects have propped up its waterfront end on a single support. Because this wide column also includes emergency exit stairs, it looks bulky, even a bit clumsy.

Still, raising the library allows the riverfront parkway to flow underneath it and gives some breathing room to the excellent landscape design by George Hargreaves. On the far side of the building, a spot has been selected for Clinton’s grave -- a site that one of the Polshek architects, Arkansas native Kevin McClurkan, calls “the site not spoken of.”

The library gains energy from its relationship with two striking structures that were already on the site: the red-brick Choctaw railway station, now renovated and home to the Clinton School of Public Service, and a rusting, skeletal bridge that used to deliver trains across the river. The station building is well-proportioned and traditional, with delicate ornament, whereas the bridge, which will soon be reopened as a pedestrian walkway, is pure engineering, leaping the river in three arcing bounds. The Clinton library, clearly, is meant to resemble both: Sleek and refined, it also goes out of its way to express its structure nearly as honestly as the bridge does.

A 12-foot-wide, double-height veranda separates the interior of the box from the glass screen that makes up its western facade, helping to mitigate the intensity of the light, particularly in the afternoons. The outer layer of glass is covered by tiny dots, and it reads almost as pure white instead of clear, particularly in the morning and evening. Tucked away on the roof is a private apartment for the Clintons -- designed in onyx, drapery and buttery pastels that clash with the floor-to-ceiling glass walls -- by the family’s favored interior decorator, Kaki Hockersmith.

Below, the main exhibition space, designed by Ralph Appelbaum Associates of New York, which also collaborated with Polshek on the Rose Center, traces the Clinton presidency through a series of shallow alcoves, made of cherry wood, on two levels. The design is inspired by the library at Trinity College in Dublin, which Clinton visited while a Rhodes Scholar. The exhibits on the lower floor trace the president’s political record, and those above focus on the Clinton family and life in the White House.

A particular alcove has been drawing lots of attention, of course: The one that describes l’affaire Lewinsky and the impeachment proceedings that followed. Like many other depictions of scandal in presidential libraries, it is not exactly impartial. Under the heading “The Fight for Power,” it includes sections on the “politics of persecution” and “culture of confrontation.” Still, this jab at the president’s adversaries has nothing on the one at the Nixon library, which compares anti-Vietnam protesters to terrorists and tries to make the case that every smoking gun in the Watergate case was firing blanks.

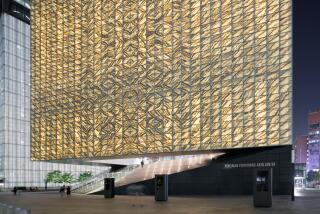

The final part of Polshek’s composition is an archives building, a small but impressive design that includes a three-story cube covered on its upper levels by perforated, corrugated metal panels. Pushed back from the river, the archive is joined to the exhibition spaces by a low connecting building and walkway. Although the archive includes roomy, technologically up-to-date study areas for presidential scholars, it’s essentially a gigantic file cabinet. One of the rooms buried inside, its compact shelving nearly bumping up against the ceiling, contains a mind-boggling 50 million documents.

Until now, Little Rock’s biggest tourist attraction has been one with a dark history: Central High School, which stood at the center of a fierce desegregation battle in 1957. Whatever the residents of Little Rock thought of the Clinton presidency, they are clearly proud to have a bright new landmark to show visitors from out of town. Still, isn’t there something slightly pessimistic about a building in the shape of a bridge that doesn’t go anywhere? Imagine the Ponte Vecchio stopping partway over the Arno, or a Golden Gate Bridge that allowed drivers to go only halfway from San Francisco to Marin. In Little Rock, we are left with a monument to a young, idealistic president that, however bold its forms, feels incomplete.

Given the rumors flying around Arkansas (and Washington) about the 2008 race for the White House, though, there exists one potential, if fantastical, solution: A Hillary Rodham Clinton presidential library, which could begin on the other side of the river, loop over, and join her husband’s. The linked buildings would provide an irresistible metaphor for this particular couple: They might draw some criticism as an architectural marriage of convenience, but they’d make a pretty formidable combination nonetheless.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.