Existence Was Relative to Einstein

- Share via

He stopped traffic on Fifth Avenue like the Beatles or Marilyn Monroe. He could’ve been president of Israel or played violin at Carnegie Hall, but he was too busy thinking. His musings on God, love and the meaning of life grace our greeting cards and day-timers. Fifty years after his death, his shock of white hair and droopy mustache still symbolize genius.

Who else could it be but Albert Einstein?

Einstein remains the foremost scientist of the modern era. Looking back 2,400 years, only Newton, Galileo and Aristotle were his equals.

Around the world, universities and academies are celebrating the 100th anniversary of Einstein’s “miracle year,” when in 1905 he published five scientific papers that fundamentally changed our grasp of space, time, light and matter. Only he could top himself about a decade later with his theory of general relativity.

Born in the era of horse-drawn carriages, his ideas launched a dazzling technological revolution that has generated more change in a century than in the previous two millenniums.

Computers, satellites, telecommunication, lasers, television and nuclear power all owe their invention to ways in which Einstein peeled back the veneer of the observable world to expose a stranger and more complicated reality underneath.

And he launched an intellectual quest for a single coherent law that governs the universe. Einstein said such a unified super-theory of everything, still unwritten, would enable us to “read the mind of God.”

“We are a different race of people than we were a century ago, utterly and completely different, because of Einstein,” said astrophysicist Michael Shara of the American Museum of Natural History.

Yet there is more, and it is why that Einstein transcends mere genius and has become our culture’s grandfatherly icon. He escaped Hitler’s Germany and devoted the rest of his life to humanitarian and pacifist causes with an authority unmatched by any scientist today, or even most politicians and religious leaders. He used his celebrity to speak out against fascism, racial prejudice and the McCarthy hearings. His FBI file ran 1,400 pages.

His letters reveal a tumultuous personal life -- married twice and indifferent toward his children while obsessed with physics. Yet he charmed lovers and admirers with poetry and sailing. Friends and neighbors fiercely protected his privacy.

And, yes, he was eccentric. With hair like that, how could he not be?

He stuck out his tongue at photographers -- that is, when he wasn’t wearing a Native American war bonnet or other get-up. Cartoonists loved him.

He never learned to drive. He would walk home from his office at Princeton University, sockless and submerged in the pursuit of the “eternal riddle,” letting his umbrella rattle against the bars of an iron fence. If it skipped a bar, he would go back to the fence’s beginning and start over.

In those solitary moments, he unconsciously demonstrated the traits -- intense concentration, disregard for fashion and innate playfulness -- that would rescue him when, inevitably, he would be interrupted by both presidents and passers-by to explain the universe.

“Once you can accept the universe as matter expanding into nothing that is something, wearing stripes with plaid comes easy,” Einstein once said.

*

Today, there are curiously few statues of the man. The most notable is a 12-foot bronze at the National Academy of Sciences in Washington depicting the wrinkled old sage gazing at his famous E = mc2 formula. Tourists climb into his lap for snapshots.

Rolf Sinclair despises it. “It’s one of the worst pieces of public sculpture,” said the retired National Science Foundation physics program officer. “It makes him look like one of the Three Stooges reading his horoscope.”

The Einstein that Sinclair and others would prefer immortalized is circa 1905, when he was 26 and about to rock the world. By day, he worked in the Swiss patent office in Bern. He called it his “cobbler’s job,” but for seven years, he analyzed a stream of inventions dealing with railroad timekeeping and other matters of precision that raised cosmic possibilities in his fertile mind.

After hours, he would work furiously on his “thought experiments” that smashed through the limits of established physics.

“Imagination is more important than knowledge,” Einstein said. “The important thing is to not stop questioning.”

In 1905, he published five landmark papers without footnotes or citations. It marked the beginning of an unrivaled, two-decade intellectual burst.

Here is a brief chronology of his miracle year:

* March 1905: Conventional physics described light as a wave and could not explain how light can knock electrons off metal. Einstein showed that light is made of tiny packets of energy, or quanta, that can behave like individual particles too.

This duality is the basis of quantum theory, a pillar of modern physics so paradoxical that even Einstein didn’t entirely buy into it. His explanation of this “photoelectric effect” won him the Nobel Prize in 1921.

* April: Based on conversations over tea, Einstein submitted a paper determining the size of sugar molecules by calculating their diffusion in the liquid.

* May: He showed how particles that appear to be independently moving in water are being jostled by atoms that are moving chaotically. Known as Brownian motion, Einstein’s calculations confirmed the atom’s existence and, by extension, the makeup of chemical elements.

* June: Einstein’s paper on “special relativity” separated him from the mainstream physics crowd. Newton considered gravity to be absolute -- mass attracts mass. It’s what makes gas and dust form stars and debris form planets.

But Einstein sought to explain anomalies in this rule. Scientists had concluded that light was just one of many kinds of electromagnetic waves moving through an unseen medium they called ether, and the speed of light is always the same.

Einstein recalled a teenage daydream of racing a light beam. According to the physics of his day, if he moved as fast as the light, then the beam would be stationary in space. Einstein said the speed of light is constant at 186,282 miles per second. But it appears different depending on where you are and how fast you are traveling. For example, clocks on orbiting satellites run a bit slower because the satellites are orbiting at 17,000 mph. They have programs that help them align with clocks on Earth.

Or suppose you were to “witness” a star exploding into a supernova. The explosion occurred thousands of years ago, but it has taken that long for the light to reach the Earth.

* November: Einstein published an extension of special relativity regarding the conversion of mass into energy, noting the “mass of a body is a measure of its energy content.” In 1907, he abbreviated it to what would become science’s most famous equation: The amount of energy equals mass times the speed of light squared, or E = mc2.

C2 is such a huge number that even small amounts of mass pack big power.

This became the theoretical basis for both atomic explosions and atomic energy.

“Each of these papers is a landmark in physics,” said S. James Gates, University of Maryland physicist. “And yet all of his work in 1905 is a prelude to his greatest composition -- the theory of general relativity.”

Special relativity was incomplete because it did not deal with gravity. To Newton, gravity was a constant, absolute force. Drop an apple and it hits the ground. A planet traces a curved orbit because the sun’s gravity tugs at the planet. In Einstein’s relative world, matter warps the time and space around it. So, the sun’s mass dents and distorts the space-time fabric, curving the planet’s trajectory.

He reasoned that even particles of light, which have tiny mass, should be affected in this way.

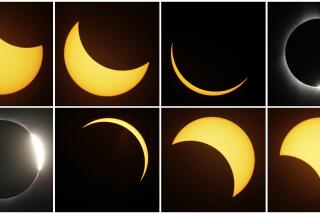

In 1919, astronomers watching a solar eclipse observed the light from a distant star being deflected by the darkening sun’s mass -- by a few hundredths of a millimeter.

General relativity laid the foundation for all kinds of theories and discoveries, such as the Big Bang, expansion of the universe and black holes.

Yet relativity is both so profound and confounding that even other physicists have trouble grasping its nuances.

Einstein described relativity this way: “Put your hand on a hot stove for a minute, and it seems like an hour. Sit with a pretty girl for an hour, and it seems like a minute. That’s relativity.”

*

In a lifetime that coincided with Rudolph Valentino and Clark Gable, it’s hard to imagine Einstein as a lady’s man. With that hair? And rumpled clothes?

He had a passionate personality that drew admirers. But physics always was his first love and that was the trouble.

The young Einstein’s indifferent, even ruthless, nature is evident in his dealings with his first wife, Mileva Maric. She and Einstein were students at the renowned Swiss National Polytechnic in Zurich. In effusive letters and poetry, he called her Dollie and himself Johnny.

She gave birth to an out-of-wedlock daughter at her parents’ home in Hungary. The baby either died or was adopted. Einstein never saw the child.

The episode ended Maric’s career before it began. She appears to have been a sounding board for his ideas, but historians doubt that she was a true collaborator. They married in 1902 and she bore two sons, but their passion soured as Einstein’s reputation grew. He complained that he had no time for marital “chatter.”

They separated in 1914.

“You make sure ... that I receive my three meals regularly in my room,” he wrote in his cold list of conditions. “You are neither to expect intimacy nor to reproach me in any way.”

But eight years later, he gave her the $32,000 from his Nobel Prize for physics.

Einstein had an affair with his German cousin, Elsa Lowenthal, who nursed him back to health when he collapsed from nervous exhaustion in 1917. They married two years later, but she soon found herself tolerating his girlfriends. They immigrated to Princeton in New Jersey, where she died in 1936.

Until his death from heart disease on April 18, 1955, relatives and his secretary kept house for Einstein at 112 Mercer St. He also developed attachments to several women who shared his love of music, sailing and world affairs.

One was an alleged Soviet spy, Margarita Konenkova, a Russian married to a Greenwich Village sculptor. Another was Johanna Fantova. She and her husband had met the scientist in Prague’s intellectual circles, which included the novelist Franz Kafka. She immigrated to the United States alone in 1939. She cut Einstein’s hair and he telephoned several times a week. In her diary, she included this charming line of verse from the physicist:

Exhausted from a silence long

This is to show you clear how strong

The thoughts of you will always sit

Up in my brain’s little attic.

As an old man, he revealed to Fantova a melancholy side.

“The physicists say that I am a mathematician, and the mathematicians say that I am a physicist,” he said. “I am a completely isolated man and though everybody knows me, there are very few people who really know me.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.