DISCOVERIES

- Share via

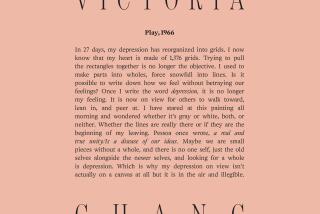

Written on Water

Eileen Chang

Translated from the Chinese

by Andrew F. Jones

Columbia University Press:

218 pp., $27.50

EILEEN CHANG, often called “the Garbo of Chinese letters,” was revered for her iridescent cultural criticism as well as for her fiction (“The Rice-Sprout Song,” “The Rouge of the North”). “Written on Water,” essays published in China in 1945 and translated into English for the first time, are set in Shanghai in the 1930s and ‘40s, during the Japanese occupation. Chang returned to Shanghai severely rattled after living through much of the war in Hong Kong, determined to record history from the margins. “I have always found myself wishing,” she wrote, “that [historians] would concern themselves more with irrelevant things. This thing we call reality is unsystematic, like seven or eight talking machines playing all at once in a chaos of sound.”

Chang took an apartment on the top floor of a building and wrote about her life, a departure for the notoriously private woman. She wrote to “let off some steam,” she explains, “so that I don’t become an insufferable chatterbox when I get old.” She liked the idea of writing on water, in the spirit of gossip. She considered herself firmly rooted in the petite bourgeoisie. “Whenever I see the term,” she wrote, “I am promptly reminded of myself, as if I had a red silk placard hanging from my chest imprinted with these very words.”

My favorite essays are those on her apartment -- with her unforgettably erudite elevator man, the hot water that bubbled up reluctantly from “the Nine Springs” deep in the earth, the sounds of daily life on the street -- and those on clothing, which contain thousands of shards of Chinese history and culture, struggle and beauty. Her descriptions of “scallion green brocade,” of collars, sleeves and the elaborate order of jackets and vests are dazzling. As are Chang’s sketches of people: “snobs looking at poor people,” “foreigners looking at Chinese,” and so on.

Chang left China in 1956 for the United States. She died in West Los Angeles in 1995 at age 75. It is the warmth and sophistication of her observations that fix her in literature. One settles in almost immediately for a chat that could last a lifetime.

*

Green Parrots

A War Surgeon’s Diary

Gino Strada, foreword by

Howard Zinn

Charta: 160 pp., $13.95 paper

As difficult as this may be to digest, the book title “Green Parrots” refers to antipersonnel mines resembling little plastic green parrots that curious children can pick up and be mutilated by. Author Gino Strada is referring to the Russian-made PFM-1 mine.

Here is what happens to children like 6-year-old Khalil in Afghanistan, when picking up a green parrot: “Traumatic amputation of one or both hands, burns on the chest and face, very often involving the eyes and resulting in blindness. Unbearable. I have too often seen children who wake up after surgery and find themselves without a leg or without an arm. They have moments of desperation, then, incredibly, they take heart again. But nothing is as unbearable for them as to wake up in the dark. The green parrots drag them into the darkness forever.”

Strada, a surgeon with a group called Emergency, writes with regret about a 12-year-old boy in Pakistan severely wounded by metallic splinters, with one eye totally destroyed, the other injured. The boy has been blind for three days without an explanation and so he tries to kill himself by wrapping a plastic bag around his head. Strada tells of children on the Iran-Iraq border being hit by a Valmara 69 land mine. Nashat, 8, and Raifat, 6, are dead on arrival; Farhad, 5, dies one hour later. (“The American people are not confronted with the daily horrors the Iraqi people have been enduring,” writes Howard Zinn in his foreword, “the dead children, the lost limbs, the burned bodies, whole families wiped out.”)

“Green Parrots,” first published in Italy in 1998, is Strada’s diary from his work around the world. “Can the civilized conscience endure this?” he asks. “I only hope that the conviction that wars, all wars, are repugnant will grow stronger in those who will decide to read these pages. And that we cannot turn our backs, to avoid seeing the faces of those who suffer in silence.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.