Itzhak Perlman wears the years like a master

- Share via

Attending a recital by violinist Itzhak Perlman isn’t too different from hearing the Rolling Stones live. You’re not buying tickets for technical perfection. You’re mindful that the decades have made their mark but still want to enjoy the results. There’s no substitute for the original -- not in the case of musical heroes.

And at his seasoned age, Perlman, 60, has maintained his indelible blend of virtuosity and charm. Classical musicians, like great rockers, keep developing complexity despite a roughening of the edges.

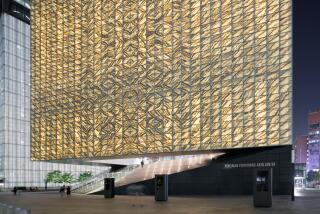

Monday night at Walt Disney Concert Hall, Perlman displayed as much pyrotechnic fire, sonic sweetness and hearty melodic shape as he did flat and uneven playing. The take-home memory was patriarchal maturity, a grand recitalist’s presence redolent of Fritz Kreisler and Jascha Heifetz.

Joined by pianist Janet Goodman Guggenheim, who played more as an accompanist than a collaborator and lagged behind her partner’s fleet tempos, Perlman opened with an everyday Mozart sonata, the F major, K. 377. The work was a clear warmup piece, but Perlman’s punky offbeat accents and nuanced textures captured its composer’s impetuous spirit.

The program’s meat was Beethoven’s “Kreutzer” Sonata, a turbulent warhorse that Perlman has owned since his intense 1973 Decca recording with pianist Vladimir Ashkenazy. On Monday, however, his rendition faced a jarring interruption from Disney Hall’s emergency alarm. “I’ve had many signs from Beethoven over the years,” Perlman half-joked as frightened listeners rose, looking for cues to evacuate. “We will try harder.”

Indeed. After calming the audience without word from Disney personnel, Perlman showed powerful command of the work’s manic energy.

Curmudgeons could have complained about his questionable intonation. But the “Kreutzer” is Perlman’s anthem. Innocuous human error could never corrupt his interpretation.

The remaining music was less challenging and engaging. Perlman doused Dvorak’s “Four Romantic Pieces” with his trademark golden tone, mensch-y musical smiles and velvet bow changes.

But by the time Smetana’s nostalgic “From My Homeland” arrived, it was clear that the second half had been designed as a mere intro for Perlman’s trademark encores: Gluck’s “Melodie” from “Orfeo ed Euridice,” Heifetz’s arrangement of Ibert’s “The Little White Donkey” and Bazzini’s “Dance of the Goblins,” a sonic carnival of double trills, down-bow staccatos, unison tones and harmonic slides that came off mildly phoned-in but exciting nonetheless.

In the end, a true artist is remembered for his character, and Perlman, as he continues to advance as a conductor and a violin teacher at Juilliard, isn’t in the game for single-game scoring records anymore. His contribution to music is about humanity.

That’s why Disney Hall didn’t have to tell its listeners to sit after the false alarm. All Perlman had to do was remain firmly in place and nod with natural fatherly strength at each section of the crowd.

Everything was going to be OK.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.