Classic ‘Parade’ marches home

- Share via

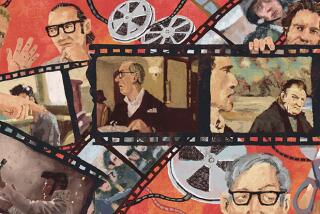

“The Big Parade,” King Vidor’s seminal World War I epic, is 80 years old this year, an occasion the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences will mark Friday with the West Coast premiere screening of a print newly restored by Warner Bros. The 19-piece Robert Israel Orchestra will accompany the silent film.

“The Big Parade,” made in 1925, two years before the creation of the motion picture academy, was envisioned by MGM simply as a low-budget programmer starring one of the studio’s young heartthrobs, John Gilbert. So the film, based on a war story by Laurence Stallings called “Plumes,” was shot on the cheap.

“It was budgeted at a quarter-million dollars,” says Richard P. May, vice president of film preservation, Warner Bros. Technical Operations. “But as they were making the film, they saw it was more than just an ordinary film.” MGM decided to promote the film heavily as a “John Gilbert special,” and it became a big hit with critics and audiences. In fact, it played 96 weeks at the Astor Theater in New York City. “The Big Parade” was the studio’s highest-grossing release until “Gone With the Wind” surpassed it 15 years later.

Not only did the film make Gilbert a superstar, it furthered the careers of Renee Adoree, who plays the young French girl who falls in love with Gilbert’s doughboy, and Karl Dane, a lanky Danish actor who nearly steals the film as Gilbert’s buddy, Slim.

After the sound revolution, MGM rereleased “The Big Parade” with a music and sound effects track in 1931.

For years, it was thought that the original nitrate negative of the film had decomposed -- nitrate film stock is unstable and combustible -- and been buried with several other disintegrated MGM nitrate negatives at the George Eastman House in Rochester, N.Y.

The only negative thought to exist was a copy MGM had made years before, when the studio copied all the nitrate negatives in its library onto safety acetate film stocks, which were nonflammable.

But “Big Parade” and several other original nitrate negatives of MGM films had never actually been buried. They were hidden in plain sight because of an inventory error.

A process of repair

Three years ago, historian and preservationist Kevin Brownlow saw the negative at the Eastman archive vault and told May of its existence. But before the fragile negative could be used for the restoration and preservation, it needed to be repaired.

As a first step, students at Eastman’s L. Jeffrey Selznick School of Film Preservation went through it, along with the 1931 duplicate negative with the soundtrack, and made meticulous notes about their condition. They did minor repairs on the negatives, then shipped them to the CFI Laboratory, the restoration division of Technicolor in North Hollywood. Preservation technician Jeff McCarty spent 200 hours in examining and further repairing the negatives so they would be able to go through a printer.

“What we did was make prints from both negatives,” says May. “The 1931 print jiggled all over the screen and had shrunk more than the 1925 negative. We would not have done a restoration with that negative. But the original one is rock steady, which was a relief.”

A few segments of the film, though, had disintegrated. “There were certain scenes that when we went through the printer you would cut from a good scene to a second scene and there was no image, just splotches. The emulsion had begun to bleach out because of decomposition. We could speculate that there was poor processing of the negative back in 1925. So those scenes were replaced with the [acetate] negative MGM had made back in the late 1960s.”

A cutting continuity from 1925 let CFI know what scenes in the black-and-white film were tinted either in blue, amber or night lavender hues to convey mood. It happened that Brownlow, a Briton, was in town during the tinting restorations and actually had examples of tintings from other films of the era with him. “CFI sent a driver [to his hotel] and we used them for a match so we know we have accuracy [in the tints].”

The technicians also relied on Brownlow’s knowledge of the film for a scene involving a Red Cross ambulance.

“He knew the cross on the ambulance was supposed to be red,” says May. That scene was scanned into the computer and a colorist digitally painted the cross red.

The original nitrate negative was sent back to Eastman, the archive has two new prints of the film and a safety negative, and Warner Bros. is storing two negatives made from the original.

The fate of the film contrasts with the lives of its three stars, all of whom met early ends. Gilbert had a difficult time making the transition to sound films -- his voice was considered weak -- and he drank heavily. He died of a heart attack in 1936 at age 36. Adoree’s career sputtered at the end of the silent era; she died of tuberculosis in 1933 at age 35.

Dane’s thick accent shut the door on his film career when sound arrived. In 1934, he bought a hot dog cart to make ends meet while studying to become a plumber. One day, after selling hot dogs outside the gate of the studio where he had once been a big star, Dane went home to his apartment and committed suicide. He was 47.

*

‘The Big Parade’

Where: Samuel Goldwyn Theater, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, 8949 Wilshire Blvd., Beverly Hills

When: 8 p.m. Friday

Price: $5

Contact: (310) 247-3600 or www.oscars.org

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.