The trauma and slaughter of World War I is examined in a new LACMA show

- Share via

World War I is something of a blank spot amid the general American habit of forgetfulness. The epic bloodbath has almost disappeared down the memory hole. It returns now as the focus of an exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, where its representation as perhaps the first “media war” gets examined.

The 1914 assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, in Sarajevo was long ago and far away, its participants and empires now a hazy history. Perhaps the recollection lapse has something to do with the delay in American entry into the brutal conflict, which didn’t come for almost three years, contravening an early declaration of determined neutrality. Or maybe the gruesome clash has just been shadowed beneath the grandiosity that grew around American power after World War II — what oral historian Studs Terkel called “the good war” — an era that split the 20th century into halves, a “before” and an “after.”

When 2023 began to unfold, pandemic-induced art museum cancellations and postponements seemed to be behind us, as programming mostly caught up. Here are 10 memorable exhibitions from the year.

Whatever the reason for neglect of the “before,” World War I was nonetheless a defining episode in global events. Some scholars even regard it as a virtual engine for many of the horrors that were to unfold over the next 100 years — up to and including the current atrocities roiling the Middle East. The battle, begun on horseback and finished with tanks and planes, killed more people (an estimated 14 million military and civilians, according to the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History), cost more (in excess of $337 billion) and involved more countries (28) than any other in all of human history. Colonial revolts, the eruption of an influenza epidemic that claimed more than 25 million lives worldwide, lasting alterations in international economic rankings — sometimes it seems that World War I changed everything.

In acknowledgment of the Treaty of Lausanne centennial, noting the last gasp of violent repercussions generated by the transformational hostility, which largely concluded in 1918, LACMA has organized “Imagined Fronts: The Great War and Global Media.” Timothy O. Benson, curator of the museum’s Robert Gore Rifkind Center for German Expressionist Studies, has pulled together about 200 objects — mostly posters, photographs, rotogravure graphics from books and newspapers, prints and film clips, plus a small number of paintings and drawings — to look at how the war was presented to an international public through emerging mass media.

Two of the few media exceptions are at opposite ends of the painting spectrum. Italian Futurist Gino Severini, who was living in Paris during its bombardment, was virtually obsessed with the industrialization of war. Belle Epoque French-Swiss painter Félix Vallotton, best known as a printmaker associated with the symbolist group Les Nabis, took on Verdun — an epic, nearly yearlong battle in eastern France.

Verdun got the better of Vallotton, painting-wise. Estimates of between 700,000 and 1 million casualties would barely be guessed from the relatively bland image in his extensively restored 1917 canvas, on loan from the Army Museum in Paris. Dense clouds of black and white smoke billow from behind a hill and beneath intersecting wedges of crisscrossed pale blue, gray and red, while flames flicker at the edges of a barren forest at the right. Rain pelts down opposite.

Weirdly, the scenery of conflagration opens in the distance to blue sky, lending a manipulative celestial touch of spiritual optimism to a landscape defined by horrors. The distant vista seems almost pretty, the resulting composition less grim than emotionally creepy.

More incisive is Severini’s well-known “Armored Train in Action” (1915), a vibrant vertical abstraction that he based on a static, high-contrast documentary photograph. It’s worth seeing the show just for this: At once explosive and claustrophobic, pressing in on itself while thrusting outward in multiple directions, the artist’s inventive, sharp-edged graphic design in blacks, grays and greens smacks of metallic violence intruding on natural landscape. A phallus merges with a cathedral. Futurism was not short on grandiose posturing, and Severini later embraced fascist politics, but the technical brilliance of his reconfiguring of fractured Parisian Cubism cannot be denied.

More common is John Armstrong Turnbull’s stylized adaptation of Cubist painting for a jazzy if conventional 1918-19 illustration of an airplane dogfight, an aerial novelty of the just-concluded war. Rather than examine painters whose work was inspired by an unfathomable conflict, it might be more productive to ponder why so few artists engaged the subject — save primarily for the antic Dada artists in Zurich and Paris, whose contrarian embrace of irrationality and nonsense as protest falls outside this show’s mass-media purview. The mechanical techniques of printmaking, photography and film may simply have been a better fit than painting for the subject of war newly defined by industrialization.

Commentary: LACMA has transitioned to a de facto contemporary art museum. But not a very good one

LACMA might be a de facto museum of contemporary art, but frankly it’s not a very good one.

Benson has organized the “Imagined Fronts” display into four sections. “Mobilizing the Masses” focuses on often-official, pro-war propaganda; “Imagining the Battlefield” includes photographs manipulated in the darkroom to intensify scenes; “Facilitating the Global War” looks at imagery beyond European subjects, including pictures of colonial African soldiers and American First Nations cryptologists; and, finally, “Containing the Aftermath” is a small survey of generally futile efforts to control repercussions from the extraordinary damage.

Individual items stand out, such as Harry R. Hopps’ “Destroy This Mad Brute! Enlist!,” a shrieking poster whose roaring gorilla sporting a German helmet and clutching a helpless damsel in distress predates by more than a decade Hollywood’s King Kong and Fay Wray. Frank Hurley’s “Death the Reaper” layers multiple photographic negatives to create a monstrous black cloud rising over the battered corpse of a soldier in a ruined field. In the adept lithograph “Angels and Airplanes,” Russia’s Natalia Goncharova gives her blessing to the erupting conflagration by entwining unearthly militarism and Orthodox religiosity.

Germany’s great Otto Dix, who enlisted in 1914 (and survived), fused an X-ray-like jumble of skulls with ghostly, shell-shocked faces featuring blank eyes and gaping mouths rendered in liquid black and gray watercolor. It might be the show’s most beautiful object — if that’s an appropriate word for such a forbidding spectacle.

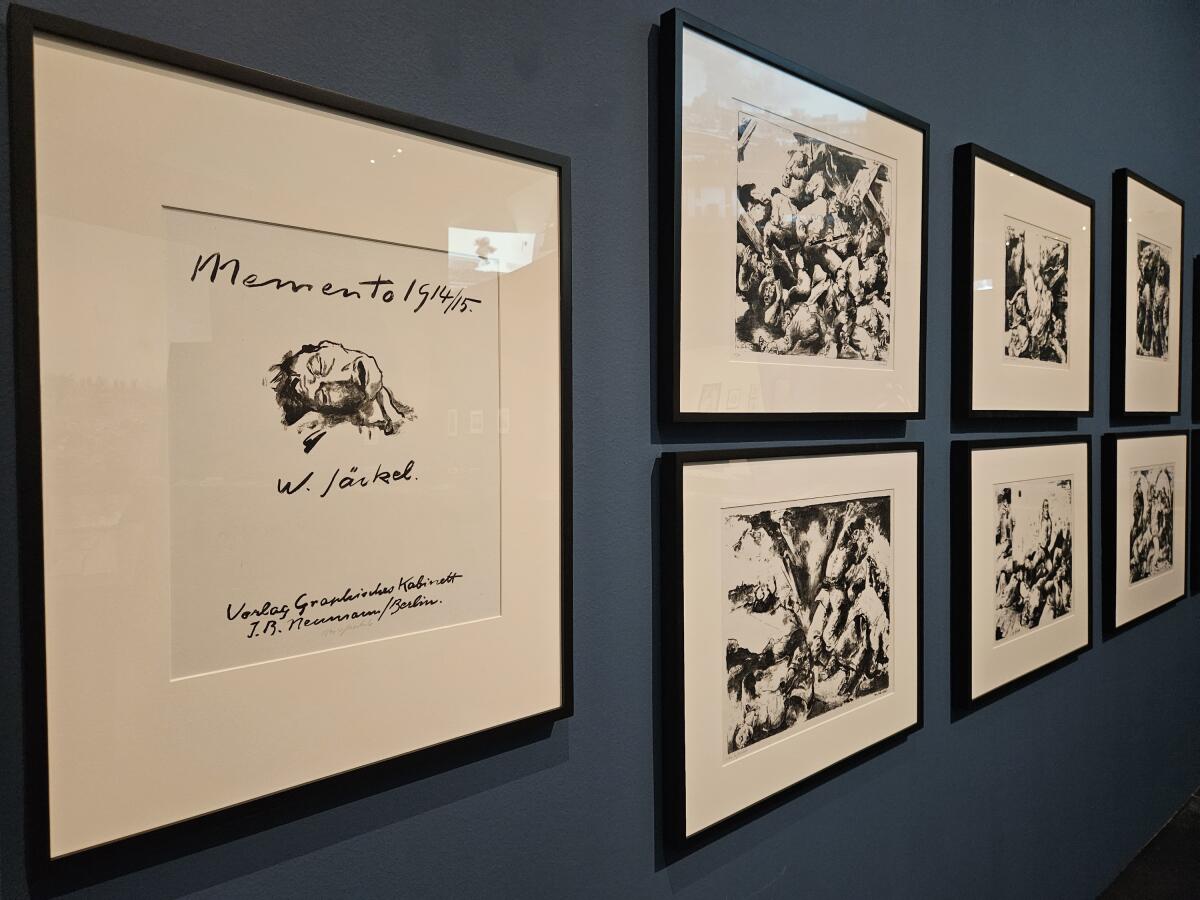

One especially riveting piece is “Memento 1914/15,” a blistering portfolio of 10 lithographs by Willy Jaeckel, made in 1915 when he joined the Berlin Secession to oppose artistic suppression by bellicose Kaiser Wilhelm II. (Jaeckel was just 27.) Inspired by Goya’s “The Disasters of War,” it features a reclining severed head on the cover page — the “sleep of reason” made permanent, its unleashed monsters manifold in subsequent sheets.

The show’s primary drawback is its selection of film clips — not because they aren’t relevant; much of the astounding German Expressionist cinema of the 1920s, for example, grew from devastating wartime trauma and military defeat. (“Nerves,” a 1919 silent film directed by Robert Reinert, presented the wartime ruin as a “nervous epidemic.”) But these, along with Hollywood productions and documentary snippets, are shown in 17 projections, most of them up at the ceiling edge overhead, above the graphics hung below. They’re simply difficult to see, especially with just two benches at opposite ends of the show.

The skied design, I suppose, means to imply that film is on the rise as a new power medium. Tablets placed on tabletops would have been friendlier, even if less suitably chaotic for the films’ battle-connected references. Prepare for a stiff neck.

Imagined Fronts: The Great War and Global Media

Where: LACMA, 5905 Wilshire Blvd., Los Angeles, CA 90036

When: Through July 7, 2024. Closed Wednesdays

Info: (323) 857-6000, www.lacma.org

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.