A writer’s gamble

- Share via

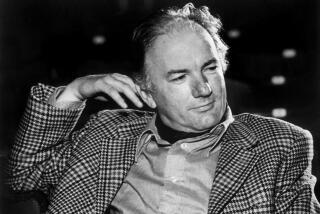

“AFTER ‘The Perfect Storm,’ I knew I didn’t want to write about the sea, meteorology or storms anymore,” Sebastian Junger said in a recent phone interview from his Cape Cod home. “I was done with that. I didn’t want to become trapped in a category where I was expected to write about only one thing.”

Following the success of his 1997 bestseller, Junger was eager to find new literary ground. He traveled overseas and started writing about war zones around the world. After the publication of these pieces in his 2001 book “Fire,” he again wanted to avoid being typecast, this time as a war correspondent. That’s when he turned to confessed Boston Strangler Albert DeSalvo’s story, which had long been a part of the Junger family’s private lore. He realized that writing about his connection to DeSalvo and a local murder posed the greatest challenge he had ever faced as a writer.

“I knew I wouldn’t be able to rely on 100-foot waves or West African civil war to carry the reader through the book,” the 44-year-old author said. “It was a supreme challenge. I had to test myself and use all of my skills as a journalist to make a quiet Boston suburb into something interesting for the average reader.”

Junger emphasized that making a story interesting doesn’t mean employing fictional techniques or resorting to the kinds of fabrications that got “A Million Little Pieces” author James Frey into a heap of trouble this year.

“For me, if there’s any fictional invention in nonfiction, then it becomes a novel,” he said. “If you have to fictionalize material, it means you can’t solve the structural problems of your story using pure journalism. If that’s the case, the writer should go back and do more research and then try again.”

Research for “A Death in Belmont” was nothing short of “a nightmare,” Junger said. Besides reams of court papers to sift through, he struggled to find anyone who remembered the killing of Bessie Goldberg 43 years ago.

One of his sources was Leah Goldberg Scheuerman, the victim’s daughter. She has since accused Junger of making factual errors and of attempting to exonerate the man initially convicted of Goldberg’s murder, Roy Smith. Junger said this is a misreading of his book. He and his publisher have offered a detailed response to her claims that can be found on the publisher’s website (www.wwnorton.com) in the entry for the book. If anything, Junger told The Times, researching the case made him less willing to argue for anyone’s guilt or innocence.

“I’m not trying to prove anything,” he said. “I found that I couldn’t do that. I couldn’t nail it down. So I decided to leave that decision to the reader. It’s a gamble, but I decided that it was an approach that had to work.”

Junger traces his skepticism with courtroom outcomes to a confusing jury duty experience he had in 2000. A New York City police officer was charged with selling stolen goods; as the trial started, the defendant’s guilt seemed clear, he said. Then the defense challenged the prosecution’s case -- and several jury members, including Junger, started second-guessing themselves about the officer (who later took a plea bargain).

“I realized that when you’re on a jury, your opinion about guilt or innocence largely depends on who is talking at the time -- the prosecution or the defense,” Junger said. “I found myself going back and forth several times a day on whether the accused was guilty or not. And that was the experience that I wanted to reproduce for my readers.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.