Hit with decision overload

- Share via

Starbucks offers consumers up to 87,000 drink combinations. Comcast, the nation’s largest cable provider, offers up to 1,000 channels. Sirius offers 140 different satellite radio stations for your listening pleasure.

Americans have come to expect a wide array of choices, and most companies, be they car companies, clothiers or coffee shops, have been more than willing to pony up. But more choices do not always equate to happier consumers.

In fact, some studies show that having to make too many decisions can leave people tired, mentally drained and more dissatisfied with their purchases. It also leads people to make poorer choices -- sometimes at a time when the choice really matters.

The notion that choice is always good for people -- the more choices the better -- seemed intuitively wrong to Kathleen Vohs, an associate professor of marketing at the University of Minnesota. “Clearly there are costs to having too much choice,” she says -- and she set out to find what they were.

Vohs, who has studied the effect of choice on consumers for many years, found in a recent project that even making pleasant choices can deplete one’s mental resources, making a person less able to concentrate later.

Students in her study who were asked to make decisions later spent less time preparing for a test, gave up more quickly when trying to complete various tasks and performed worse on math problems than those not asked to make choices.

Vohs’ group also studied the “decision fatigue” that can occur at a shopping mall. They asked random shoppers at a Utah mall questions such as how many decisions they had made that day, the importance of those choices and the length of their deliberation. The researchers found that the more choices the shoppers had made, the worse they performed on simple math problems they were then asked to complete on the spot.

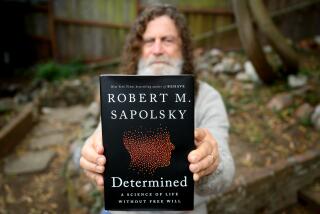

Making decisions takes work, says Barry Schwartz, a professor of psychology at Swarthmore College and author of the 2004 book, “The Paradox of Choice: Why More Is Less.”

“The mere act of thinking about whether you prefer A or B tires you out,” Schwartz says. “So if I give you something else that takes discipline, you can’t do it -- you’ll quit faster. If I have lifted weights in a gym, later trying to lift a 30-pound weight is impossible.”

Schwartz says that one of three things is likely to occur when people have too many decisions to make -- consumers end up making poor decisions, are more dissatisfied with their choices or become paralyzed and don’t choose at all.

And as the complexity of a decision increases, a person is more likely to look for ways -- often erroneous -- to simplify the choosing process. If there are 100 kinds of cereal, instead of looking at all of the characteristics, people will evaluate a product based on something familiar, such as brand name, or easy, such as price.

Even when we choose well, we are often less satisfied because, with so many choices, consumers are certain that somewhere out there was something better. “They think about attractive things they’ve passed up and missed opportunities,” Schwartz says.

Schwartz recently fell victim to this when purchasing a pair of jeans. He went to the Gap and tried on all the available styles. He walked out with jeans that fit well, but he was still not happy with his purchase, he says. With so many different varieties of pants, he was left thinking, “One of them should have been perfect -- and none were.”

Most marketers are aware that consumers succumb to the idea that more options means we’re more likely to find the perfect product.

And most companies use this fact of human psychology to their advantage. Because creating a new brand of shampoo or laundry detergent is expensive, companies often save money by marketing products that differ only slightly from their competitors’ products or other brands of their own. Then they spend time convincing buyers that the products are, in fact, very different, says Sheena Iyengar, a professor at the Columbia University Graduate School of Business.

“How different are 400 types of bottle water?” Iyengar asks. (The answer to her rhetorical question: hardly at all.)

“More and more choice does not guarantee better options, just more of them,” Iyengar says. “If customers wise up to the idea that marketers and retailers are using tricks of differentiation, retailers will stop creating the fluffy options.”

The final problem with decision-making is that it can overwhelm people to the point of their making a default choice or no choice at all.

A 2000 study by Iyengar and colleagues in an upscale California grocery found that consumers were 10 times more likely to purchase jam when offered six kinds instead of 24. In other words, faced with too many choices, some threw up their hands and opted to buy no jam.

And in another study in 2007, employees who were offered a large variety of options for a 401(k) were more likely to allocate their savings into less complex money market or bond funds rather than select among the many stock mutual funds, which are more lucrative over the long run.

“This potentially is quite detrimental,” Schwartz says. “You are debilitating yourself making inconsequential decisions” -- such as which jam to buy or which jeans to buy or what kind of coffee beverage you’ll have to drink that morning. “Then,” he says, “something important arises and that machinery is not working at optimal capacity because you wasted it doing all this choosing.”

Of course, you can always opt to purchase from a grocery store that offers fewer choices (Trader Joe’s and Fresh & Easy, for example). But there’s no getting away from the fact that a plethora of consumer choices is likely to remain around to tantalize and torture us. (See our tip box on a few ways to minimize decisions.)

“I don’t think we have the option to reduce choices so that we go to a world where we only have seven of everything,” Iyengar says. “As a society, we just need to be given better tools on how to choose.”

--

--

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX)

How to deal with all the options

Choices, choices. What’s an inundated consumer to do? Experts have a number of tips.

* Sometimes it’s good to rely on habit -- “put the blinders on and get the same toothpaste you always get,” says Barry Schwartz, a professor of psychology at Swarthmore College.

* If you want to purchase something new, call a friend who has one already and get his or her recommendation.

* You can sometimes delegate decision making to others; for example, if you are going to dinner, let your spouse decide where to eat.

* Accept that a good option is almost always good enough. When you find something that meets your standards, stop looking, buy it and be happy.

* People can also learn to make decisions by understanding their own preferences and creating a structure for decision making, says Sheena Iyengar, a professor at the Columbia University Graduate School of Business. For example, instead of taking your 4-year-old to a grocery store and asking which of the myriad kinds of cereal she wants, give her some structure. Break them into smaller categories -- such as chocolate, whole grain or ones with fruit added -- and take the rest out of consideration. By putting them into a couple of categories, and then determining from there which she would like best, you simplify her decision.

-- Tammy Worth

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.