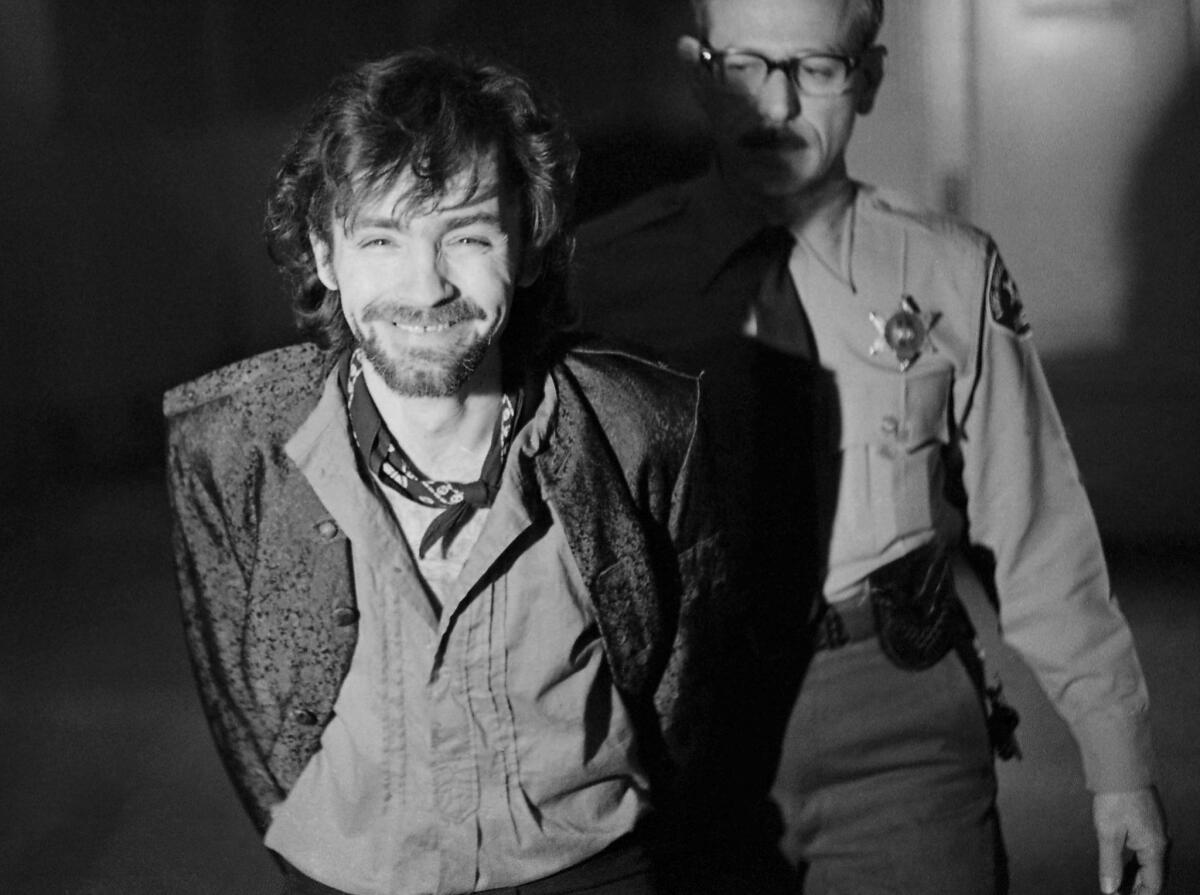

Will the real Charles Manson stand up? A new book retraces his steps.

- Share via

Early in Jeff Guinn’s “Manson: The Life and Times of Charles Manson,” the first full biography of the infamous mass killer, there’s a moment of unexpected and discomforting empathy. It’s 1939, and Manson — 5 years old, living with relatives in West Virginia while his mother is in state prison for armed robbery — has embarrassed himself by crying in a first-grade class. To toughen him up, his uncle takes one of his daughter’s dresses and orders the boy to wear it to school.

“Maybe his mother and Uncle Luther were bad influences,” Guinn writes, “but Charlie could benefit from Uncle Bill’s intercession. It didn’t matter what some teacher had done to make him cry; what was important was to do something drastic that would convince Charlie never to act like a sissy again.”

That’s a key moment in “Manson” — both for what it does and for what it cannot do. On the one hand, it opens up our sense of Guinn’s subject, establishing him in a single brush stroke as more than just a monster, as a broken human being. On the other, it ends so quickly, without revealing what happened once he got to class, that it never achieves the necessary resonance.

If, as Guinn appears to be saying, we can only understand Manson by knowing where he came from, then we need to see, in full detail, those roots. Yet despite his access to Manson’s cousin Jo Ann (whose dress the boy was forced to wear) and his half-sister Nancy, neither of whom has previously consented to be interviewed, Guinn can’t overcome a basic problem of construction: that before 1967, when he was released from Terminal Island and moved to the Bay Area, there’s just not enough hard information available to bring the 1960s psycho poster child to life.

Guinn is not the first writer to come up against these limitations: In his 1971 portrait “The Family,” Ed Sanders manages one brief chapter tracing Manson’s evolution from check-kiter and car thief to “peripatetic collector of walking wounded war children,” while in the still-definitive “Helter Skelter” (1974), Vincent Bugliosi and Curt Gentry largely avoid the subject other than to wonder, “What happened to transform a small-time hood into one of the most notorious mass murderers of our time?”

Neither “The Family” nor “Helter Skelter,” however, is a biography, so the burden of expectation is not the same. Guinn promises a life story rather than a history of the killings that plunged Los Angeles into panicked frenzy when, in August 1969, Manson family members murdered actress Sharon Tate and four others on Cielo Drive in Benedict Canyon and on the following night Leno and Rosemary LaBianca at their home in Los Feliz.

Of course, there was always more to Manson than Tate-LaBianca — more craziness, more self-deception and more death. Born in 1934 to a teenage mother, he was apparently manipulative and violent from the start. Guinn fleshes out his early existence with choice anecdotes: In addition to the one about the dress, he offers a chilling recollection from the late 1940s, in which the then-13-year-old stole a gun while pretending to take a shower. (He used the sound of running water as cover.)

And yet, despite these flashes, Manson’s early years remain sketchy — until he lands in prison and his life as we have come to know it begins. It was during his first stint at Terminal Island, in the 1950s for car theft, that Manson picked up a key bit of information, gleaned from talking to pimps.

As Guinn explains, “You had to know how to pick out just the right girls, Charlie learned, the ones with self-image or Daddy problems who’d buy into come-ons from a smooth talker.... You wanted girls who were cracked but not broken. The trick was to make them love you and fear you at the same time.”

Such a strategy would enable him to build the Family, collecting lost souls (there were plenty in late 1960s Los Angeles and San Francisco) and slowly bending them to his will.

Guinn — who was a 2010 Edgar Award finalist and has written more than a dozen books, including “Go Down Together: The True, Untold Story of Bonnie and Clyde” — does a workmanlike job of taking us through the basic plot: Manson’s meeting Mary Brunner in Berkeley in 1967, his recruiting of Squeaky Fromme and Patricia Krenwinkel and then the others, his obsession with becoming a rock star who would put the Beatles to shame.

This is among the weirdest aspects of the story, his collaboration with Beach Boy Dennis Wilson (the band’s 1969 song “Never Learn Not to Love” grew out of Manson’s composition “Cease to Exist”) and the access Wilson offered to producers such as Terry Melcher, for whom the future killer auditioned. At the same time, Guinn can’t keep himself from overstatement, framing music as the central motivation when it was just one face of a tangled psychosis, in which for both Manson and the Family the line between reality and fantasy grew irrevocably blurred.

As “Manson” progresses, this becomes increasingly problematic, as Guinn seeks to explain the inexplicable. In his view, Manson was nothing but an opportunist, turning on “the ‘Crazy Charlie’ act that he’s performed to perfection” while remaining shrewd and controlling underneath. To his credit, he’s dug up some new information — including the way Manson and co-defendants Krenwinkel, Susan Atkins and Leslie Van Houten orchestrated supposedly spontaneous courtroom outbursts during their 1970-71 murder trial — but his portrayal gives Manson too much credit and paradoxically not enough.

That’s particularly apparent when it comes to the Tate-LaBianca killings, which were less planned acts of savage chaos than spur-of-the-moment reactions to events that had gotten out of hand. Here, we see Manson at his least effective, sputtering about race war (his dream of Helter Skelter depended on all-out conflict between whites and blacks) while conceiving of these gruesome murders to throw police off the trail of Family associate Bobby Beausoleil, who had been arrested for killing music teacher Gary Hinman in an extortion/robbery gone wrong. It’s a complex mix of motivations, and it reveals Manson as both more ruthless and less manipulative than he wanted his followers to believe.

Ultimately, this brings us back to that first-grade classroom and the humiliation that we never fully see. To what extent did his early experiences turn that boy in the dress into the architect of Helter Skelter? This is the challenge Guinn has undertaken, and it’s a valiant one, if unachievable in the end.

Why does Manson continue to compel us? Not because he reflects the dark heart of the 1960s but because he exemplifies a more far-reaching darkness, the one inside ourselves. As he said at his trial, “I am only what you made me” — like every persuasive liar, nurturing his deceptions from a kernel of truth.

Manson

The Life and Times of Charles Manson

Jeff Guinn

Simon & Schuster: 496 pp., $27.50

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.