Review: Lori Roy’s skills impress in ‘Let Me Die in His Footsteps’

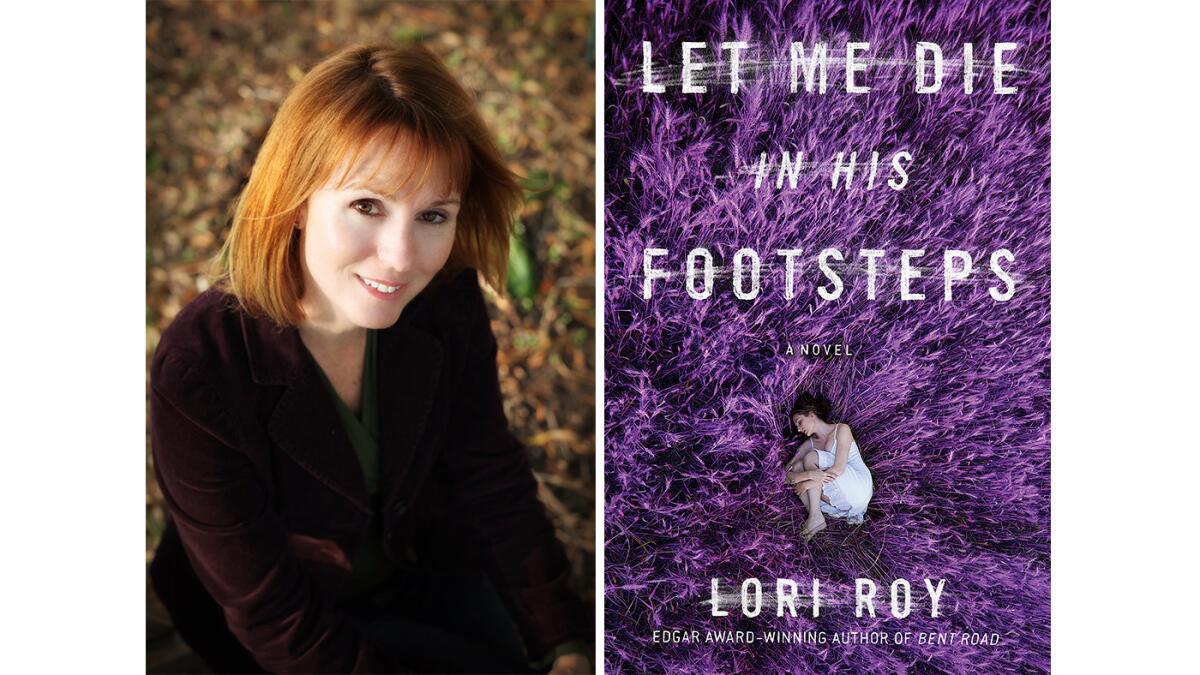

Author Lori Roy and the cover of the book “Let Me Die in His Footsteps’

- Share via

Lori Roy’s first two novels were nominated for Edgar Allan Poe Awards, with “Bent Road” taking the prize — the mystery equivalent of an Oscar — for best first novel. Her third novel, “Let Me Die in His Footsteps,” is a hybrid of mystery, coming-of-age and Southern gothic literature, inspired by the last lawful public hanging in the United States. It continues her track record of dark, creepy excellence.

Annie Holleran has the know-how, a gift and curse that passes from mother to daughter. The know-how is an unstructured, nonspecific sort of clairvoyance, a sharpened awareness that’s more country mystic than fantasy. She “feels things that aren’t hers to feel” and “has a way of knowing how things will end before their end has come.” She has inherited this gift not from her Mama Sarah but from Sarah’s sister Juna Crowley, whom she and the rest of her town know to be her birth mother.

In 1952, she turns 151/2, the age of ascension in her rural Kentucky town, with a sense of premonition — “All these many days, there’s been something in the air, a spark, a crackle, something that’s felt a terrible lot like trouble coming.” That night, she and her sister Caroline stumble on the dead body of their elderly neighbor, Cora Baine.

Sixteen years earlier, Baine’s son, Joseph Carl, was hanged on the basis of accusations levied by Juna, who disappeared from town shortly afterward. Despite Carl’s conviction and execution, it is Juna’s legacy that contains the whiff of evil — “[She] isn’t the good kind of a legend, but the kind that has wrapped itself around the Holleran family and hung there for almost twenty years.”

Juna has inspired schoolyard chants and left the townspeople uneasy about Annie, who shares her blond hair and black eyes, and maybe, as Annie has feared all her life, her taint of evil. With another Baine dead, Annie dreads and anticipates the return of the mother she has never met.

The narrative alternates between 1952 and 1936, relating the events of those years from Annie’s and Sarah’s points of view. Though the novel follows two timelines, the story is very much unified, the voices and motifs echoing each other, the past sprouting up in the present, the present providing resolution to the past. “Our histories root themselves right where we stand, and they lie in wait until they can soak up into the next generation and the next,” Annie learns from her grandmother. “It’s what feeds us.”

The secrets of 1936, their accompanying love, rivalry, deceit and evil — all of this colors the happenings and relationships that make up Annie’s life. Roy does wonderful work weaving her complementary narratives into a naturally cohesive novel, and the central mystery — of what happened between Juna and Joseph Carl — unravels in a way that is simultaneously elegant and unexpected.

Though this mystery provides its engine, the novel demonstrates an undeniable literary bent. The language is easy to read, but it’s taut and evocative — things simmer and tickle and sizzle underfoot, and the book practically smells like a lavender field. The characters are vividly drawn, the women in particular (I got a chill from this line: “Ever so slightly, she turns folks in the direction of her liking”).

Even the town has a developed personality, every denizen complicit in the hasty execution of Carl, despite uncertainty about his guilt. They’re poor and desperate and stagnant, and they want to see someone punished. “They’ll rid themselves of something evil, and their lives will be good again.”

If the novel has a major failure, it’s largely one of omission. Roy was inspired by accounts of Rainey Bethea’s hanging in Owensboro, Ky. Bethea was a black man. Roy doesn’t pretend to tell his story, but for a novel that engages with the American South (and focuses on a hanging, of all things), “Let Me Die in His Footsteps” is almost obstinately white, the burdens of difference and marginalization visited on blond girls with black eyes. There are many decent excuses for this decision, but the result feels a bit incomplete.

The novel is impressive nonetheless, carefully crafted with a compelling vision and well-honed prose. Scenes between sisters are as rife with tension as sequences played out with cigarettes glowing in the dark; not a sentence or detail is wasted. For those of us without the know-how, there’s shock and satisfaction when “the truth starts pushing its way up and out.”

Cha is the author, most recently, of “Beware Beware.”

Let Me Die in His Footsteps

A Novel

Lori Roy

Dutton: 336 pp., $26.95

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.