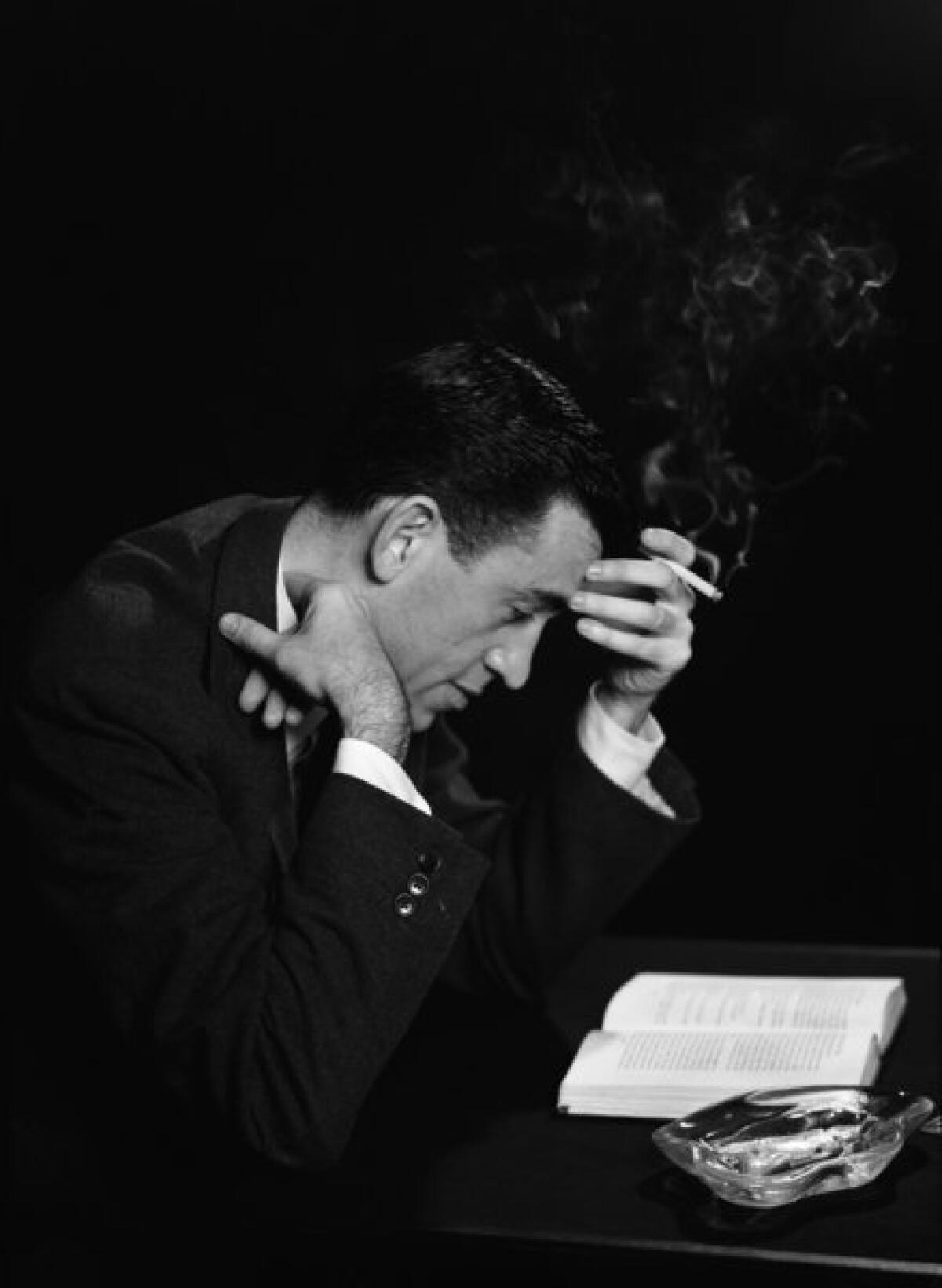

Throwback Thursday: Our 1963 review of J.D. Salinger

- Share via

Fifty years ago, J.D. Salinger was a bestseller.

In June 1963, Salinger was making top 10 lists with his book “Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters,” which also included “Seymour: An Introduction.” That the two long stories (or short novellas) had previously been published in the New Yorker -- in 1955 and 1959, respectively -- didn’t quell readers’ eagerness to buy the book.

For Throwback Thursday, we’re sharing our 1963 review -- back then the hardcover, published by Little, Brown, cost $4.

L.A. Times book critic Robert Kirsh wrote that Salinger, “in a homey note,” explained the purpose of pairing the two pieces together. Kirsch quotes Salinger’s note, which read, in part: “Whatever their differences in mood or effect, they are both very much concerned with Seymour Glass, who is the main character in my still-uncompleted series about the Glass family. It struck me that they had better be collected together, if not deliberately paired off, in something of a hurry, if I mean them to avoid unduly or undesirably close contact with new material in the series. There is only my word for it, granted, but I have several new Glass stories coming along -- waxing, dilating -- each in its own way, but I suspect the less said about them, in mixed company, the better.”

In 2013, it’s fascinating to see Salinger fanning the flames of his own mythology. He promises new material! He’s got it close at hand! It’s coming very soon! And yet he never published a Glass book. There was only ever one more Glass story -- “Hapworth 16, 1924,” published in 1965 in the New Yorker -- and after that, Salinger ceased publishing completely. No wonder people have speculated that Salinger had file cabinets full of complete, unpublished works stashed away when he died in 2010 at age 91.

All this was before that, though, when Salinger was engaging with the world. In his introducion, Salinger continued, “Oddly, the joys and satsifaction of working on the Glass family peculiarly increase and deepen for me with the years. I can’t say why, though. Not, at least, outside the casino proper of my fiction.”

Kirsch picked up from there. “We continue to wait in anticipation like the man living next to a vacant lot on which a new house is being built by an eccentric do-it-yourselfer who comes from season to season, doing a little work at a time. We have not yet seen the whole shape of the house. This time the builder brought with him some bits and pieces and a strange blue print.

“Neither one of these pieces is very impressive except in the odd conversational mode employed by Buddy Glass, who still sounds vaguely like a junior philosophy major sounding off at a table in the Student Union. This, though he is much older, 40 in ‘Seymour.’

“ ‘Seymour’ is not really a story at all; it is notes on a character, a catalogue of oddments, told confidentially to Glass’s ‘old fair-weather friend of the general reader.’ He adds some airy comments on writing itself. ‘In the way of anything as large and consuming as happiness, he necessarily forfeits the smaller but, for a writer, always rather exquisite pleasure of appearing on the page serenely sitting on a fence. Worst of all, I think, he’s no longer in a position to look after the reader’s most immediate want; namely, to see the author get the hell on with his story.’ True, true.

“His credo stated, he goes on to Seymour, who you will remember is Buddy’s late, eldest brother, who committed suicide while vacationing down in Florida with his wife. Now we are finding out what Seymour meant to the Glass family. We could not know from that story in which he died. He seemed to us a very mentally disturbed fellow, who ended his life for what seemed good and sufficient reasons to him at the time.

“But to the Glass family, ‘he was all real things’: ‘Our blue-striped unicorn, our double-lensed burning glass, our consultant genius, our portable conscience, our supercargo, and our one full poet ... also our rather notorious ‘mystic’ and ‘unbalanced type’.’ He was ‘a mukta, a ringding enlightened man, a God-knower. At any rate, his character lends itself to no legitimate sort of narrative compactness.’

“Buddy apologizes for the panegyric but he can’t help himself. ‘Seymour once said that all we do our whole lives is go from one little piece of Holy Ground to the next. Is he never wrong?’

“I am tempted to ask the same question,” Kirsch writes dryly. “I am beginning to be sorry I ever started reading about the Glass family in the peculiar way, I mean, finding these fragments scattered around like torn parts of a Tibetan praying wheel, there is mystery here. There is symbolism. I hang around waiting for the next New Yorker. I can’t help myself. I’m hooked.”

ALSO:

A.M. Homes wins Women’s Prize for Fiction

Jennifer Lawrence to star in adaptation of ‘Rules of Inheritance’

A rare-book bonanza in the digital age? ‘Common Sense’ says yes

Carolyn Kellogg: Join me on Twitter, Facebook and Google+

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.