Book Review: ‘Reading My Father: A Memoir’ by Alexandra Styron

- Share via

Reading My Father: A Memoir

Alexandra Styron

Scribner: 304 pp., $25

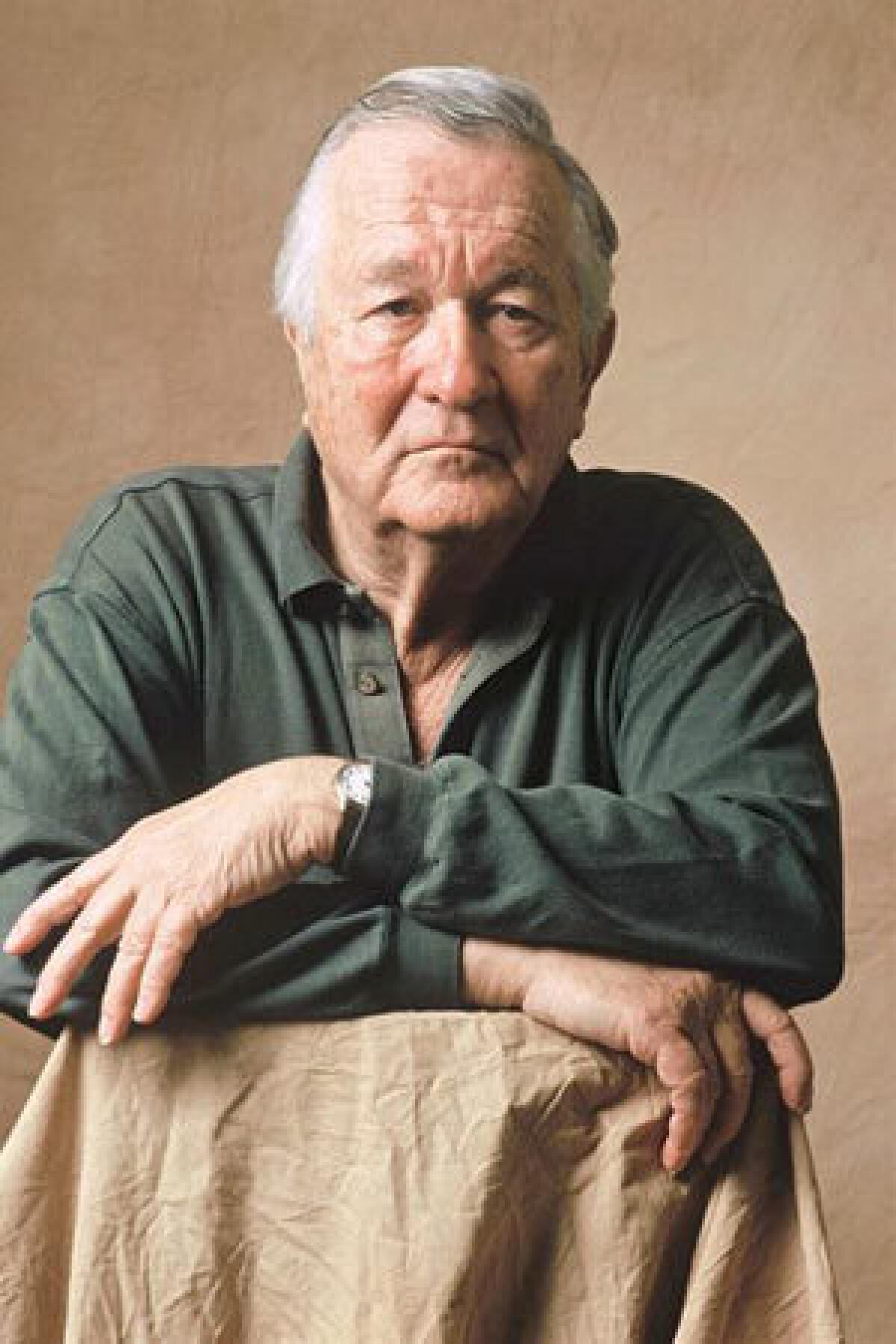

A Virginia boy who loved Proust and Dickinson, William Styron gave such heft and meaning to mid-20th century American fiction that, with a few other white male writers, he all but defined it. That he did so on the strength of only a handful of novels in 30 years, three of them extraordinary (“Lie Down in Darkness,” “The Confessions of Nat Turner” and “Sophie’s Choice”), testifies to the magisterial reach of his fiction as well as the Camelot-era longing for it. Those were the years when history could still be contained, or so we assumed, by the power of narrative, and the bigger the narrative the better.

Nearly a match for Styron’s towering talent was his persona, adorned with copious amounts of booze and machismo and Southern charm. With his wife, Rose, he maintained a glittering social arena between their homes in Roxbury, Conn., and the island of Martha’s Vineyard. And yet all that would recede in the public’s imagination with the appearance, in 1990, of “Darkness Visible,” Styron’s searing account of the suicidal depression that struck him at age 60. The book not only dispelled the myth of the lion-hearted writer; it also hauled clinical depression into the light of day where it belonged. Behind the international laurels and two-fisted drinking was a story that rivaled those of Peyton Loftis and Nat Turner for its unhinged terrors — only this one wasn’t fiction.

Of course, tragedy is ironic only when it’s happening to someone else. Styron’s was a tough act to shadow, as Alexandra Styron, the youngest of the four Styron children by several years, makes bracingly clear in “Reading My Father.” Struggling to reconcile public myth and personal truth, she puts it somewhat less delicately: “How could a guy whose thoughts elicit this much pathos have been, for so many years, such a monumental {jerk} to the people closest to him?”

Oh, those sins of the father. You may not be able to libel the dead, but you can sure make them look bad. By turns riveting and heart-rending, “Reading My Father” had, according to its acknowledgements, the blessing of the rest of the Styron family. And certainly its author displays her share of compassion, despite her occasional lapses into crudeness. The portrait that emerges is one of a withholding, sometimes cruel father who preferred the sanctuary of work to the messier realm of family. Alexandra was the daughter who opened the wine for her parents at dinner, the one whom Styron liked to call Albert, who got all his jokes and shared his particularly mordant sense of humor. (And suffered from it: When he tired of her equestrian phase, he told her that her beloved horse was headed for the glue factory. She was 8.) After his death in 2006, she immersed herself in his papers at Duke, talked to his biographer and editor and legions of friends. But the most compelling part of this memoir-cum-biography is the primary source of Styron herself — a girl who lived for the glow of her father’s limelight, yet fled the household and its tensions as soon as she had the chance.

“Reading My Father” revisits the “unexamined but corrosive” sorrows that haunted Styron throughout his life: his mother’s death from cancer when he was 14, his father’s subsequent “rest” in the hospital for a few weeks. Trying to make sense of her father’s past through the lens of her own, Alexandra Styron shifts between nostalgia and the incongruity of memory; she describes some of the high-flying days of the Styrons as though they were magical, though once you’re aware of what lurks behind those A-list dinner parties, they come off sounding rather awful. A poet and activist, Rose had family money that allowed her some flight and independence, which she would need to endure the years of her husband’s hypochondria, infidelity and depressive rages. “Melancholy when he was sober and rageful when in his cups,” writes Alexandra Styron, “he inspired fear and loathing in us a good deal more often than it feels comfortable to admit.” Rose’s notes for her husband’s medical history are more succinct but no less sad: “often angry, down on world and/or me, pattern over yrs, when not in middle of a book.”

Despite the recovery outlined in “Darkness Visible,” Styron’s depression would return, horrid and mostly unrelenting, for the last decade of his life. And the reams of unfinished pages that Alexandra found at Duke only underscored the creative chaos that went hand-in-glove with the despair. Throughout Styron’s fiction was a protagonist who knew too well the territory of Dante’s dark wood; the most autobiographical of them was a young soldier — like Styron, a second lieutenant in the Marines — preoccupied with suicide. It was a story he would never finish. The daughter tries to play critic to the father’s work, postulating that he wrestled for years with the elusive subject of war, but she is on shakier ground here than on the terrain of memory.

A story told by the smallest child in the room, “Reading My Father” can’t help being ambivalent: proud, angry, mournful of the father Alexandra Styron couldn’t have, who worshiped above all else the great god of art. Or maybe that’s another myth, too fine and gauzy, for a far less romantic tale — that of a man who loved plenty but not well, who hurt his family and drank too much and had a vast talent. On the other side of his first breakdown, in 1990, I spent two days interviewing Styron at his home on Martha’s Vineyard. Because of what he told me about the legacies of depression, I think it’s fair to give him the last word.

“There’s a kind of victory involved,” he said. “And you know, I don’t think it changes your character radically; you still have all the faults and dark sides that you had before. You have sharper insights about some things, perhaps. But you’re not turned into a saint because you’ve been through a crucible.”

Caldwell is the author of two memoirs, “Let’s Take the Long Way Home” and “A Strong West Wind,” and the former chief book critic of the Boston Globe. She was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for criticism in 2001.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.