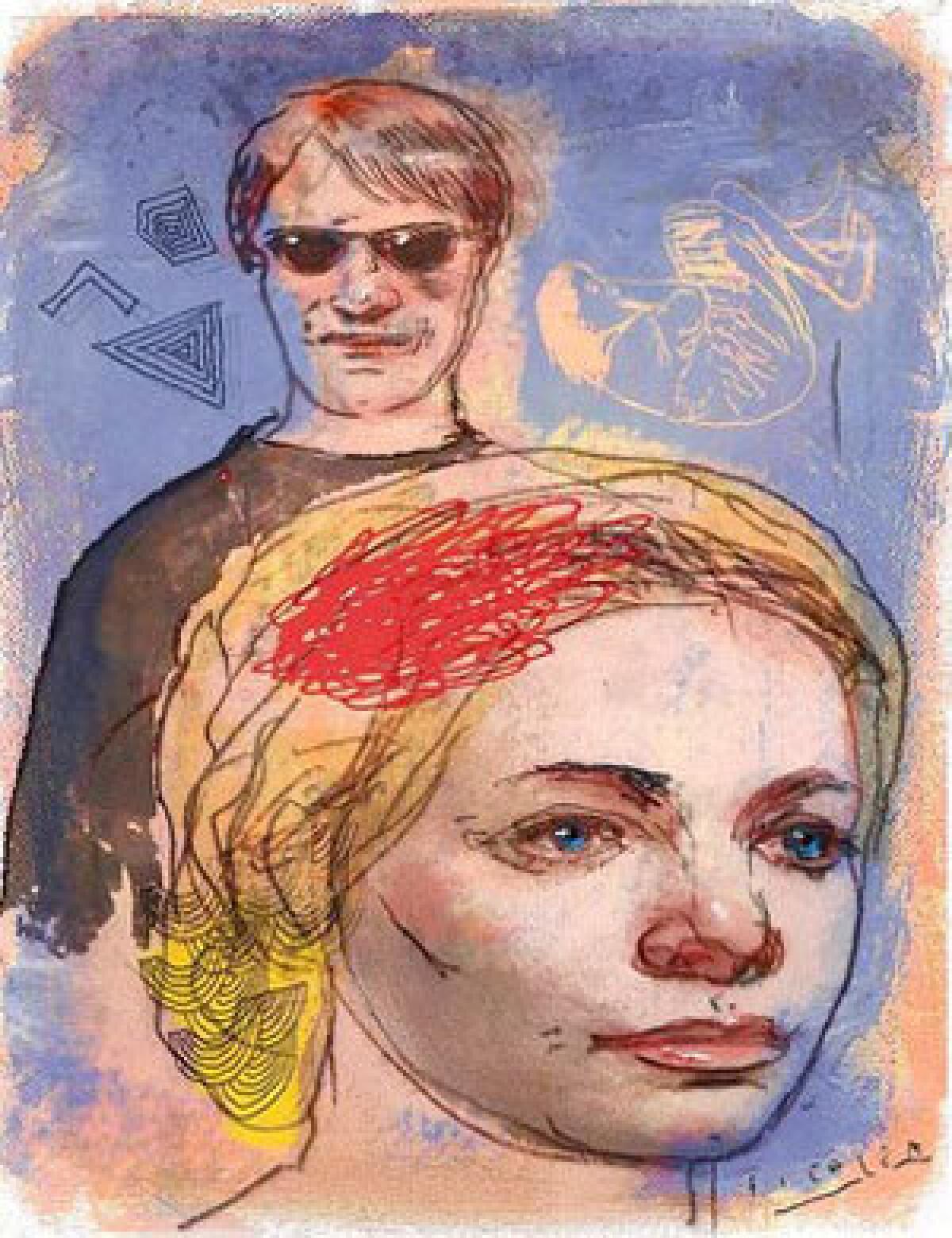

Book Review: ‘Stone Arabia’ by Dana Spiotta

- Share via

Stone Arabia

A Novel

Dana Spiotta

Scribner: 240 pp., $24

Is there a more electrifying novelist working than Dana Spiotta? Her first book, “Lightning Field” (2001) was a smart Hollywood satire about a restaurant manager who, even as her life unravels, seeks meaning in the interstices, the transition points, because such moments are the only ones that remain unobserved. Her second, the National Book Award-nominated “Eat the Document” (2006), uses the figure of Mary Whittaker, a former 1960s radical who has shed her past and gone underground, to examine the nature of identity, evoking a character who “would have lived her new life so long that the conjuring of the old life would seem like a dream, an act of imagination. Eventually it would almost feel as though it had never happened. This was the way it was supposed to go down. A secret held so long that even you no longer believe it isn’t really you.”

Both books trace the process by which politics or lifestyle can become an existential condition, making us rethink ourselves. Who are we? these novels ask. What is the relationship between our most private longings and the face we show the world?

Spiotta’s third novel, “Stone Arabia,” traffics in similar material: memory, identity, the tenuous bonds of family, the fragility of everything we hold close. It is also a meditation on celebrity and stardom, although like “Eat the Document,” it frames its big themes less as cultural phenomena than as a set of philosophical terms.

The story of Nik Worth, nearly 50, a former rock ‘n’ roll wunderkind who dropped out of sight but continued to make music, “Stone Arabia” is a novel of obsession — although whose obsession is not always clear. There’s Nik but also his sister Denise, who narrates much of the book and offers a necessary counterpoint to his interior fantasies, as well as their mother, a septuagenarian in the midstages of dementia, sloughing off the stuff of personality like so many desiccated skins.

“Pay attention to this,” Denise reminds herself as she embraces the older woman. “Hug tight, this could be one of the last hugs.” It is her sense of tenuousness, her belief that the best we can hope for is a temporary respite from the loss of living, that underlies the novel, investing even the most mundane gestures with a tragic inevitability. As Denise observes of her mother: “I grew accustomed to the idea that things would not improve and at some point I hoped to grow accustomed to the idea that they would not even maintain.”

The same is true of Nik, who also relies on Denise to prop up his sense of self. For 25 years, he has been making records on a four-track in a garage studio, creating covers and label art, and sending them to his sister and some friends. At the same time, he has developed a self-referential narrative called the Chronicles: dozens of scrapbooks filled with clippings, articles, reviews. That none of these artifacts are, strictly speaking, real is beside the point — or, more accurately, it is the point, the point at which fantasy and reality merge.

“Nik’s Chronicles adhered to the facts and then didn’t,” Denise explains. “When Nik’s dog died in real life, his dog died in the Chronicles. But in the Chronicles he got a big funeral and a tribute album. Fans sent thousands of condolence cards. But it wasn’t always clear what was conjured. The music for the tribute album for the dog actually exists, as does the cover art for it.… But the fan letters didn’t exist. In this way Nik chronicled his years in minute-but-twisted detail.”

Here, Spiotta makes plain the terms of her narrative, which has to do with the way we all chronicle our years in minute-but-twisted detail, rendering and re-rendering our experience until we can get it to cohere. That this is an inherently conditional process makes it no less essential or universal; it just bestows another sort of grace. Nik, after all, is not delusional: He knows the difference between reality and fantasy.

And yet, just look at his reality: middle-aged, awash in booze, cigarettes and other substances (“He wouldn’t call it an addiction,” Spiotta tells us. “He would call it his consolation”), still possessed of a younger man’s charm as it begins to fade. He works as a bartender, has lived in the same studio apartment for more than 20 years. Against such a backdrop, it’s no leap to suggest that his life as a fantasy rock star is the very thing that keeps him sane.

If nothing else, this makes for a sharp character study: A portrait of the artist as middle-aged never-was. Yet Spiotta’s genius is to recognize that Nik’s journey is representative not just for his sister or his mother but for every one of us. The issue is authenticity, which in a society such as this one, saturated with images and trivia, becomes perhaps the most elusive grail.

Denise is a perfect example, fixated on the effluvia of the culture: news feeds, celebrity gossip, terror scares. “This is the thing,” she admits, “the shame: my memory is dominated by events external to my actual life. These events, for whatever reason, stick in my mind and become secondhand memories.”

On the one hand, Spiotta is drawing a parallel between Denise and Nik, with his invented history, and between both of them and their mother, whose memory has disappeared. But her real point is not to frame a parallel but an opposition, since for Nik, the internal world “was his own exclusive interest now and had been for years.” It is imagination that is the driving force here, and if Spiotta’s too smart to suggest that it might save us, she does see it as the source of a futile reverence. “No one,” she writes, “— not me, certainly — could deny that this was a form of purity.”

In the end, “Stone Arabia” is about just this form of purity, the idea that life and meaning are what we make of them, even (or especially) when the connections have broken down. “It wasn’t fake; it was real,” Nik explains late in the novel. “Imagine being freed from sense and only have to pursue pure sound. Imagine letting go of explanations, or misinterpretations, of commerce and receptions. Imagine doing whatever you want with everything that went before you.” This is the aesthetic of Spiotta’s novel, and it sounds entirely genuine to me.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.