‘The Border’ is Don Winslow’s final chapter in a chilling, timely and seminal drug war trilogy

- Share via

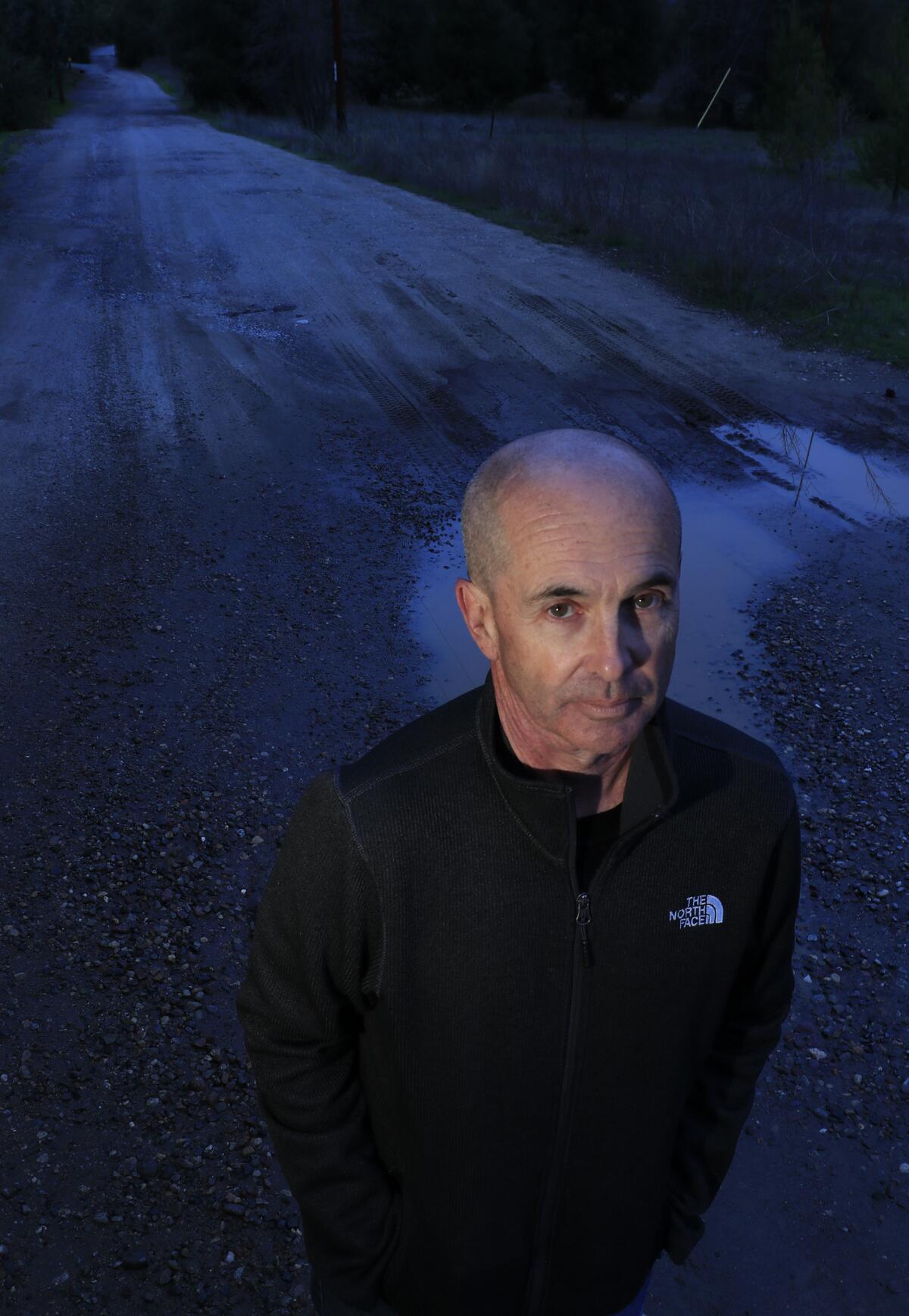

Reporting from Julian, CA — A car stops on a hilltop. A man gets out. He walks a few paces and stands at the ridge. The desert valley stretches to Scissors Crossing, where tiny armies of migrants and drug mules once slipped through box canyons in summer swelter and winter frost. They don’t come so much anymore, but when the man sees them he thinks of night whispers and lost things.

He scans south toward Mexico and then to the Santa Ana Mountains. Clouds clamp the horizon; snow glints in the distant north. The meth labs are pretty much gone, the tweakers too. But drugs, like seasons, run in cycles. The land is what grabs you, though, the way it scrunches and wrinkles and spreads out ancient and flat. Full of stories and violent souls that slither through the books of Don Winslow, a parish kid from Rhode Island who never took to the stink of the fish factory and became one of the country’s best crime novelists.

Winslow steps away from the ridge and slides into his Mustang. He starts the engine; jazz plays soft in the speakers. He checks the rear view, taps the gas. It’s a time of saying goodbye to made-up men and women.

The central question of crime fiction is how do you live decently in an indecent world.

— Novelist Don Winslow

The last book in his trilogy on America’s drug wars — a seminal work that spirals from cartel towns to the White House — will be published Feb. 26. “The Border” is intricate, mean and swift, a sprawling canvass of characters including narco kingpins, a Guatemalan stowaway, a Staten Island heroin addict, a kinky hit woman, a barely veiled Donald Trump and DEA agent Art Keller, who over the arc of the trilogy has been noble and merciless, a conflicted wanderer who makes America face the transgressions committed in its name.

“With the exception of my wife and son I’ve spent more time with Keller than any other person in my life,” says Winslow, a onetime private investigator who specialized in arson cases. “Keller and me. Five-thirty a.m. every morning. He’s kind of a sad guy I think. I don’t know if I like him or not. He’s gone. I’m not mourning him but it’s a little weird. Keller and I have a lot in common. We both come from that Catholic thing. That guilt-driven moral absolutism.”

Winslow is 5 foot 6 and weighs “a buck thirty.” He has the smooth, inviting voice of a confessor, a man who listens for revealing cracks in things. He runs on exactitude and resilience; 12-hour writing days, a punching bag in his office and a view of a roadside sign that reads: “1 cord oak $300.” He roams a 30-acre ranch and is attuned to the odd fact: the lady who makes pies in the Gold Rush town of Julian, he says, will not hire left-handed helpers because they can’t get the crust indentations right. Seriously.

Granular detail and sharp dialogue have made his drug war trilogy propulsive and compelling. Comprising “The Power of the Dog” (2005), “The Cartel” (2015) and “The Border,” the books, spanning nearly 2,000 pages, are fiction bolted to real life. They pierce and illuminate our times and draw on Winslow’s research into government policies, criminal investigations, autopsies, murder videos, newspaper stories, pharmaceutical companies, diaries of addicts, the potency of fentanyl and how 1930s gangster Bugsy Siegel opened the drug conduit from Mexico.

The stories unravel broken lives caught in a mesmerizing mosaic fueled by addiction and haunted by bloodshed. The trilogy traces how the drug trade streaked from provincial to global, defying and outflanking Mexican authorities and a string of U.S. presidents who, despite tougher laws, bigger jails and militarized police forces, could not curb the seething cunning of cartels and America’s perpetual need for a fix from the poppy fields. That led to a brutality that killed at least 100,000 Mexicans and built empires for drug lords like El Chapo, who was convicted this month in New York.

In a review of “The Cartel,” Janet Maslin wrote in the New York Times of the book’s “gasp-inducing knowledge of true crime’s brutal extremes, and for its unflinching awareness of what Mr. Winslow calls ‘evil beyond the possibility of redemption.’ Even tougher than the outright violence is the slow destruction of idealists ... who think they can escape the long shadow of this ugliness, and who one after another are proved horribly wrong.”

The border — he lives about 40 miles north of Mexico in San Diego County — is personal to Winslow. Trump’s calls for a border wall, he says, won’t stop major traffickers. “It’s so foolish. It makes me crazy,” says the author who over Twitter last week challenged Trump to a debate: “Any show. Any anchor. Any time,” he tweeted. “I’d pay $10,000 to see that!” author Stephen King added over Twitter.

“Ninety-five percent of illicit drugs come through 52 legal points of entry. Build a wall, but it will always have gates and the trucks will go through them, one every 15 seconds,” Winslow says. “What the wall could potentially do is force the little guys to go to the cartels and enrich the cartels.”

I don’t think there’s any other genre that is so intertwined as the crime genre with film and novel. You can’t separate them.

— Novelist Don Winslow

A traveler and military historian, Winslow, who has written 19 books, spent five years leading photographic safaris in Africa (He speaks Swahili). His days as a private investigator taught him about human nature and how “memory is constructed more on present needs than past reality.” He found a voice in the twisted tales of men and women facing corruption from within and without. They spin as if morality parables, dodging bullets, wisecracks, unmarked graves and killers like Belinda in “The Border” who craves sex as much as she enjoys pouring acid on a betrayer’s feet and hanging him from a yacht’s mast.

“The central question of crime fiction is how do you live decently in an indecent world,” he says. “I’ve had the great joy of reading people who are really great at it. From the poetry of Raymond Chandler to the realism of James Ellroy to what Michael Connelly and Dennis Lehane do. They show us humanity in extremis.”

Before novels, when he was a boy in Rhode Island, where he won only one of 73 hockey fights, he read stories about the New England mob wars. Newspapers ruled then, stacked on corners, intriguing, snapping open in morning light. He discovered New York columnist Jimmy Breslin, whose grit and sparse vernacular brought grifters and working stiffs to life. The son of a librarian and a sailor, Winslow had an inkling he might become a writer, notably after his father hauled him to a fish factory and told him that was his fate if he didn’t study. He started paying attention to what to words could do.

Keller. He’s kind of a sad guy I think. I don’t know if I like him or not. He’s gone.

— Novelist Don Winslow on his trilogy’s character DEA agent Art Keller

“Bruce Springsteen I think is the poet of the American era,” he says, a sliver of reverence seeping in. “There’s a lyric that ends ‘Darkness on the Edge of Town’ that I think is the crime fiction writer’s creed. ‘Tonight I’ll be on that hill ’cause I can’t stop. I’ll be on that hill with everything I got. With our lives on the line where dreams are found and lost. I’ll be there on time and I’ll pay the cost. For wanting things that can only be found in the darkness on the edge of town.’ That’s the crime novel. Bam.”

Winslow’s stories are sweeping and cinematic. Oliver Stone turned his “Savages,” the misadventures of two Laguna Beach marijuana growers who collide with drug lords, into a movie. Ridley Scott is developing “The Cartel.” Winslow’s visual sense was instilled when he was a boy buying $26 train tickets from Providence to New York to watch movies on Broadway. “The French Connection” — Gene Hackman as Detective Jimmy ‘Popeye’ Doyle caught in the grip of the international heroin trade — left a mark.

“I don’t think there’s any other genre that is so intertwined as the crime genre with film and novel. You can’t separate them,” Winslow says. “They have been informed by each other from the time they started rolling the camera. Noir particularly. Look, I never sat in my office as a PI where a trumpet started and a long-legged blond walked into the room. It was my wife and I was home with a jazz record on, but that soundtrack of noir informs me when I sit down to write.”

You can hear it in this passage from “The Border”: “Drunken, undisciplined, underperforming, wonderful Pablo, dizzy with love for his child, for (hopelessly) his ex-wife, for his beloved, shattered city. Pablo wasn’t so much a Mexican as he was a Juarense; his world began and ended within the limits of the border town, on the edge of both Mexico and the United States, its location simultaneously its reason for being and the reason for its destruction.”

So many crime fiction novels, TV series and films portray Latinos as scrambling across borders or trafficking drugs. They are caricatures easily demonized in our politically divisive era. Winslow’s depictions of such nether worlds are woven with deeper portraits, including journalists in “The Cartel” who lead the reader into the art, music and nightlife of Mexico, and Keller’s wife, Marisol Cisneros, in “The Border,” a doctor with a steely moral compass.

It’s lunchtime. Winslow stops at his favorite place for tacos. A woman calls him “the nicest man in the world.” A guy in a cowboy hat talks to him about baseball, and another hurries by disheveled and out of sorts. Winslow asks how he is. The man shakes his head and turns away. Winslow finishes lunch and walks to Orchard Lane, mentioning that sometimes a migrant, skimming the edge of town like a breeze, will freeze to death in the twilight.

He gets into his car. The road ascends and curves, looping skyward. There are cougars up here, he says. Memories too. Like the 2003 wildfires that left people shoeless and wandering fields, and then, as if a healing vision, Buddhist nuns appearing out of the gray mist with coats and blankets. He has dreams about those days. Black soil, trees slanted like battered totems from a war. That’s what happens when you live in a place for 22 years; the land takes part of you and you take part of it. A writer becomes his geography.

“You know,” he says, “after the fires children were afraid of clouds because they thought it was smoke.”

The car crests the hill. Stops. A gust kicks and dies. The sky is metal and splintered with winter light. He gets out stands on the ridge, pointing here and there, close and far away, to the things he’s seen, hidden people scurrying over unknown terrain, carrying things, stripped of things; drug mules winding to points north and east to feed a nation’s vast addiction. You can see where “The Border” trilogy came from, rising and twisting like a vicious hymn from the earth.

“I’m done writing about it, but I’ll never make peace with it,” he says.

It’s quiet, the air cold.

“You ready?” someone asks.

“Yeah,” he says.

He gets in the car. The rain has held off, but a storm is coming.

ALSO

‘Vice’ and ‘Leave No Trace’ expose the sins and casualties of the Iraq war

See the most-read stories this hour »

Twitter: @JeffreyLAT

ALSO

‘Vice’ and ‘Leave No Trace’ expose the sins and casualties of the Iraq war

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.