Review: The existentialists come alive (over cocktails) in Sarah Bakewell’s ‘At the Existentialist Cafe’

- Share via

In 1946, jazz-loving existentialists in Paris would leave the cafés and hit the dive bars, where, according to one bon vivant, they’d refuse entry to those who didn’t look right but “would admit anyone ‘so long as they were interesting — that is, if they had a book under their arm.’”

Bibliophiles will feel equally welcome arriving “At the Existential Café,” Sarah Bakewell’s vivid and warmly engaging intellectual history. It is an exemplar of the notion that “books come from books.” This is a text that sings the writing life — of the existentialists, of their critics and of their biographers.

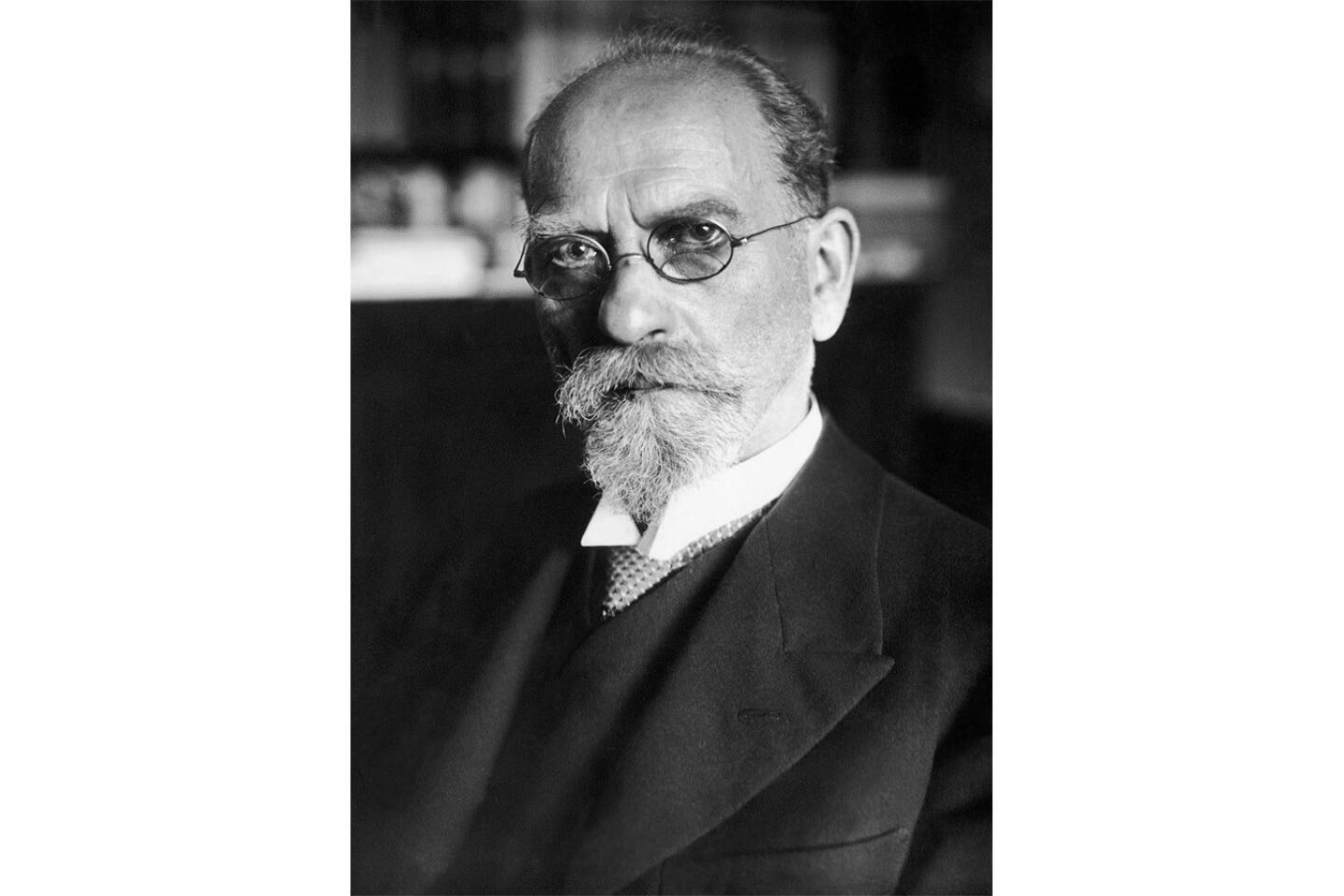

Bakewell, a former London book curator who studied philosophy at the University of Leeds, likes wordy subtitles. Here she plunks one on her fourth work of nonfiction: “Freedom, Being, and Apricot Cocktails with Jean Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Albert Camus, Martin Heidegger, Edmund Husserl, Karl Jaspers, Maurice Merleau-Ponty and others.” She isn’t kidding about the others —- the book finishes with a roll call “Cast of Characters” that runs 79 names long. Even the screenplays of Terrence Malick, with their heavy doses of Martin Heidegger, swing briefly into view. She draws on each one, symphonically, to make a case for existentialism as more pertinent to the 21st century than a nostalgia for black turtlenecks, booze, cigarettes and rebellious alienation.

The alcohol figures on the first page, “near the turn of 1932-3 when three young philosophers were sitting in the Bec-de-Gaz bar on the rue du Montparnasse in Paris, catching up on gossip and drinking the house specialty, apricot cocktails.” De Beauvoir was 25, her boyfriend Sartre was 27 and his school chum Raymond Aron was describing a new train of thought, “phenomenology,” which demands a close scrutiny of the elements of everyday life, “the things themselves.” As Beauvoir recounted it, Aron — just back from Berlin — exclaimed, “If you are a phenomenologist, you can talk about this cocktail and make philosophy out of it!” Sartre reportedly went pale — intoxicated by the potential in wedding philosophy to normal, lived experience instead of dusty, dead tomes.

This exchange, Bakewell says, was the birth of modern existentialism. One might argue, but it’s more fun to be swept up in her crisp, biography-powered history in which Sartre escapes a prisoner-of-war camp by making an ophthalmology appointment and walking out the front gate, and a young Hannah Arendt becomes the only individual in Heidegger’s wide orbit to confront him before World War II about his cozying up to Nazism.

Like Jim Holt’s superb and jaunty 2012 philosophical exploration, “Why Does the World Exist?” (sporting a nighttime cover photo of the existentialist haunt Café de Flores), Bakewell’s book offers an autobiographical hand to hold through a parade of big ideas. She tucks in a picture of herself at 17, beguiled to discover Sartre’s breakout novel “Nausea.” She mentions her pleasure that a Charlie Chaplin comedy may have triggered a key existential epiphany about the necessity of freedom in art. And she reads alongside her reader, revisiting Heidegger to exclaim, “half of me says ‘what nonsense’ while the other half is re-enchanted.”

De Beauvoir would approve of this approach. She wrote four autobiographical books whose details soak into the fabric of “At the Existential Café.” Bakewell argues that the close observations and deep discontents of Beauvoir’s “The Second Sex” (1949) is the towering achievement in existentialist literature.

Further, Bakewell writes, this masterpiece should have entered the modern canon alongside the books of Karl Marx, Charles Darwin and Sigmund Freud. It exploded deeply cherished cultural myths, not in relation to economics, biology or the unconscious but in our lives as gendered beings.

What went wrong? Bakewell suggests the fault lay in a gutted English translation, a soft-porn-ish paperback cover and generic sexism. There is also the fact that “in philosophy, as in many other fields, applied studies tend to be dismissed as postscripts to more serious works.”

“At the Existential Café” anchors itself in the harrowing particulars of 20th century European history. It follows Bakewell’s “How to Live,” a celebrated and unconventional bestseller about the Renaissance genius Michel de Montaigne. That book rewarded its readers with a seat at a 4-century-long dinner party at which the essays of Montaigne are bowdlerized by the Catholic Church, then rescued and taken up Rene Descartes, Blaise Pascal, Friedrich Nietzsche and Virginia Woolf.

When Bakewell started reading philosophy, the ideas lighted her up. “Thirty years later, I have come to the opposite conclusion,” she writes. “Ideas are interesting, but people are vastly more so.” Cannily, she marries the life of the mind with the contradictory, ornery, embodied individuals carrying these ideas around even as they fight and flirt, circle one another and fall out. It makes the pages fly.

As Bakewell notes, people still struggle to lead authentic, free and ethical lives. “That is why, when reading Sartre on freedom, Beauvoir on the subtle mechanisms of oppression, Kierkegaard on anxiety, Albert Camus on rebellion, Heidegger on technology and Merleau-Ponty on cognitive science, one sometimes feels one is reading the latest news,” she writes.

All of it — the news and the philosophy — no doubt goes down better with an apricot cocktail. The complex world certainly make better sense “At the Existential Café.”

Long manages the Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards for the Cleveland Foundation.

::

At the Existentialist Café: Freedom, Being and Apricot Cocktails

Sarah Bakewell

Other Press: 448 pp., $25

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.