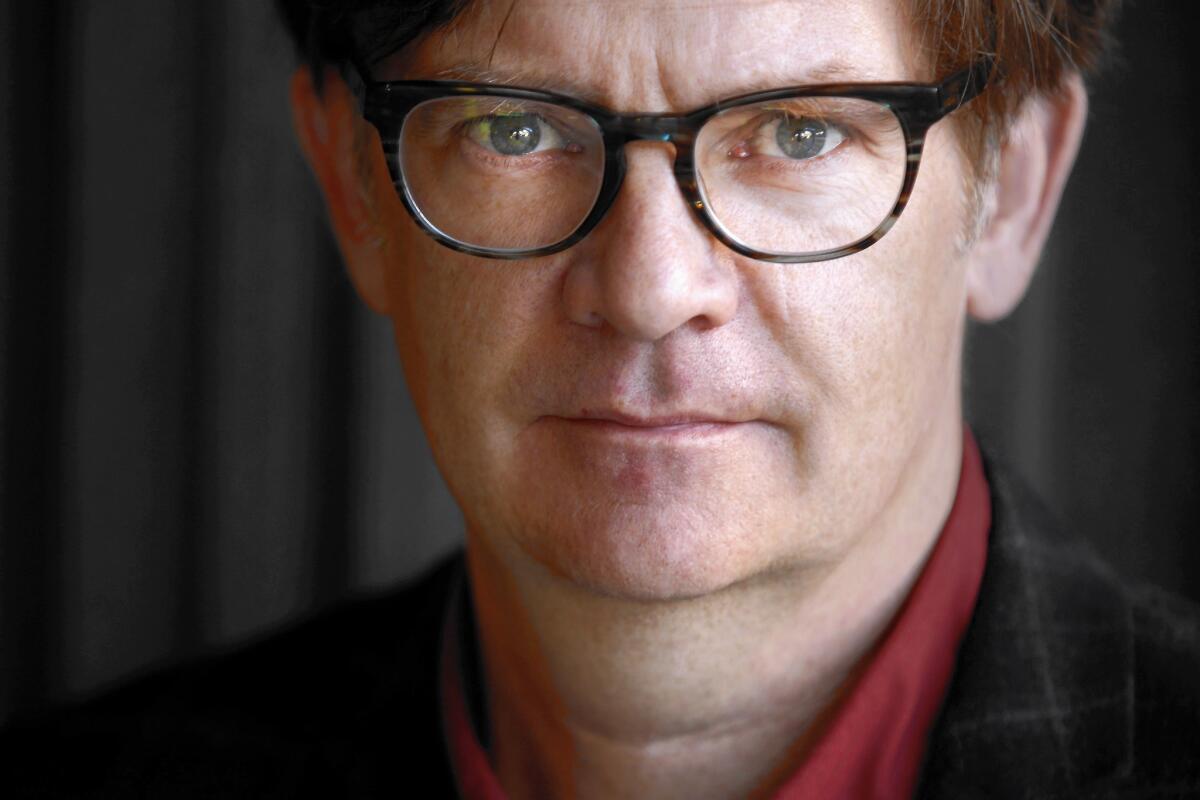

Rob Spillman on remaking himself amid the rubble of the past in ‘All Tomorrow’s Parties’

- Share via

For a memoir that ends quite well — Rob Spillman’s first 25 years see the writer triumph over multiple car crashes, titanic drinking and the dicier corners of urban neighborhoods to go on and co-found Tin House, one of America’s most influential literary magazines, with an associated publishing mini-empire — it sure has a dark title. An aching dirge sung by Nico on the Velvet Underground’s first album, “All Tomorrow’s Parties” epitomizes art rock’s rejection of easy beauty. The book is Spillman’s account of his own search for the psychic equivalent, a place that will act as a whetstone for creativity’s blade.

We talked by phone the day his crosscountry tour for “All Tomorrow’s Parties” (Grove Press: 400 pp., $25) was kicking off in New York City — “30 events in 30 days,” he said with mingled incredulity and anticipation. It’s a day that had been 10 years coming, the length of time he wrestled with the raw material of an artist’s emblematic youth, wandering from dark into shots of light and back into shadow, finally to emerge into sunshine of his own manufacture. It’s the light of self-knowledge.

Spillman grew up in Berlin, the son of expatriate musicians who eventually separated, trading him back and forth between professional postings in places as diverse as Aspen, Colo., Chautauqua, N.Y., and Baltimore. He spent his young adulthood trying to find his way back to a place that felt like home. For a moment — an indelibly exciting one — it was Berlin again, just after the Wall came down, and East Berlin was fully open to the West again after almost three decades. Spillman and his new bride, writer Elissa Schappell, knew they were present “on the cusp of something weird and quite possibly wonderful.”

Music is the beginning of his story, literally and structurally; each chapter is given its own soundtrack, a collected playlist of personally meaningful work heavy on the restively avant-garde (Lou Reed, Public Image Ltd., Joy Division, Sonic Youth).

“Music has a primal effect, I think,” Spillman said. “When I heard punk, it was like, ‘Is anyone else hearing this?’ It was everything the classical music I grew up with was not. I have visceral problems with opera” — notwithstanding the backstage perks he enjoyed as a precocious youngster given bit parts in his father’s productions — “mainly its aspect of social privilege.”

Spillman cites the Talking Heads as being transformative. “Hearing ‘Psycho Killer’ for the first time, it was as if this strange, tense, weird voice came into my room to speak to me alone.”

The 1977 song spoke to those who burned with inchoate rage, who developed a youthful taste for nihilism that new wave and post-punk met head-on. Spillman allows that now, almost 40 years later, what he feels is more a rage to instead of rage against, except where inequality is concerned: “I still rage at that, gender, racial, inequality of any kind.” In general, though, “I try to channel it more productively now.”

His chosen method is the rigorous practice of art, both his own and the work he seeks for Tin House magazine. “I absolutely love what William Gass said about his motivation: ‘I write because I hate. A lot. Hard.’”

Now that Spillman has become something of a vizier of the literary world (with the jewel in the turban to show for it, the 2015 PEN Nora Magid Award for Editing), he aims to use his stature to right publishing’s traditional imbalance toward the white and financially secure. He heads the membership committee of PEN, has long striven to “give a platform to underrepresented voices,” is working with Brooklyn College to bring greater diversity to the ground floor of the publishing complex and has just returned from story exchanges in Israel and Palestine.

There and in places like Nairobi, he finds the same sort of creative ferment he found in Berlin 25 years ago. “Artists are good at scenting out opportunity in the ruins. It happened in the Bombay of Salman Rushdie’s time, it happened in the East Village of the ‘70s, it’s happening now in Africa. Throw in revolutionary politics and you have the perfect conditions for very engaged, energetic art.”

Spillman had a magnetic attraction to the fervor of a culture that was remaking itself out of the joyfully destroyed rubble of the old — and there was no more promising or ominous rubble than that of East Berlin in 1990. “It seemed like our generation’s Spanish Civil War,” he said. “I heard a call to action, felt a sense that if I didn’t get there then, I’d kick myself later.” Creature comforts were hard to come by in the squats, but that is not what Spillman was looking for; indeed, it was a point of pride to live off discards. In return, he got to experience the transporting ecstasy of being where history was being made.

We come next to the inevitability of what happens after artists have colonized a desolate neighborhood and figured out how to do without hot water (though never without beer, even if they had to convoy it in). After a place is made safe again, the hard way, it becomes safe for money. When it arrives, the artists go. Having lived in Brooklyn for 18 years with Schappell and their children and having witnessed a couple of cycles of the transformation, he says, “New York does feel like home, though I worry about it.” No longer is Berlin or New York what it was, a thrilling “ground zero in the battle between commodification and artistic utopia,” as he writes.

Spillman’s daughter, of college age, has just visited Berlin. The places her father described in his book are all but unrecognizable. The Prenzlauer Berg district where her parents and their compatriots lived on the edge of destitution is now pricey, “like Park Slope, sidewalks filled with double-wide strollers,” he says with sad resignation.

Once a member of a band of outsiders, Spillman become the consummate insider. It’s a time-honored process, one his book allows us to witness in its formative stage. He went to the edge to find the center.

The book charts the first part of his effort to remake himself, from an impossibly restless youth to one more or less settled in a paradoxical commitment to remaining creatively unsettled. If the first theme of “All Tomorrow’s Parties” is that peculiar power of music to collar the young and pull them into the embrace of their tribe, then the second is reinvention — personal, geographic and artistic. “My favorite thing in the world is to read something I’d thought couldn’t be done. When I find a writer who can do that, everything feels new again.”

Pierson is a critic and the author of five books, including “The Place You Love Is Gone” and 2015’s “The Secret History of Kindness.”

Spillman will appear at the Los Angeles Times Festival of Books on Saturday.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.