Fox oral history: Inside the legendary studio at the end of its run

- Share via

Fox star Shirley Temple trying to coax a china-dish hen to lay an egg so she can make an omelet, in the kitchen of Temple’s bungalow cottage on the Fox studio lot, 1934.

Twentieth Century Fox was once known as Hollywood’s dream factory. Soon, it will be a part of history.

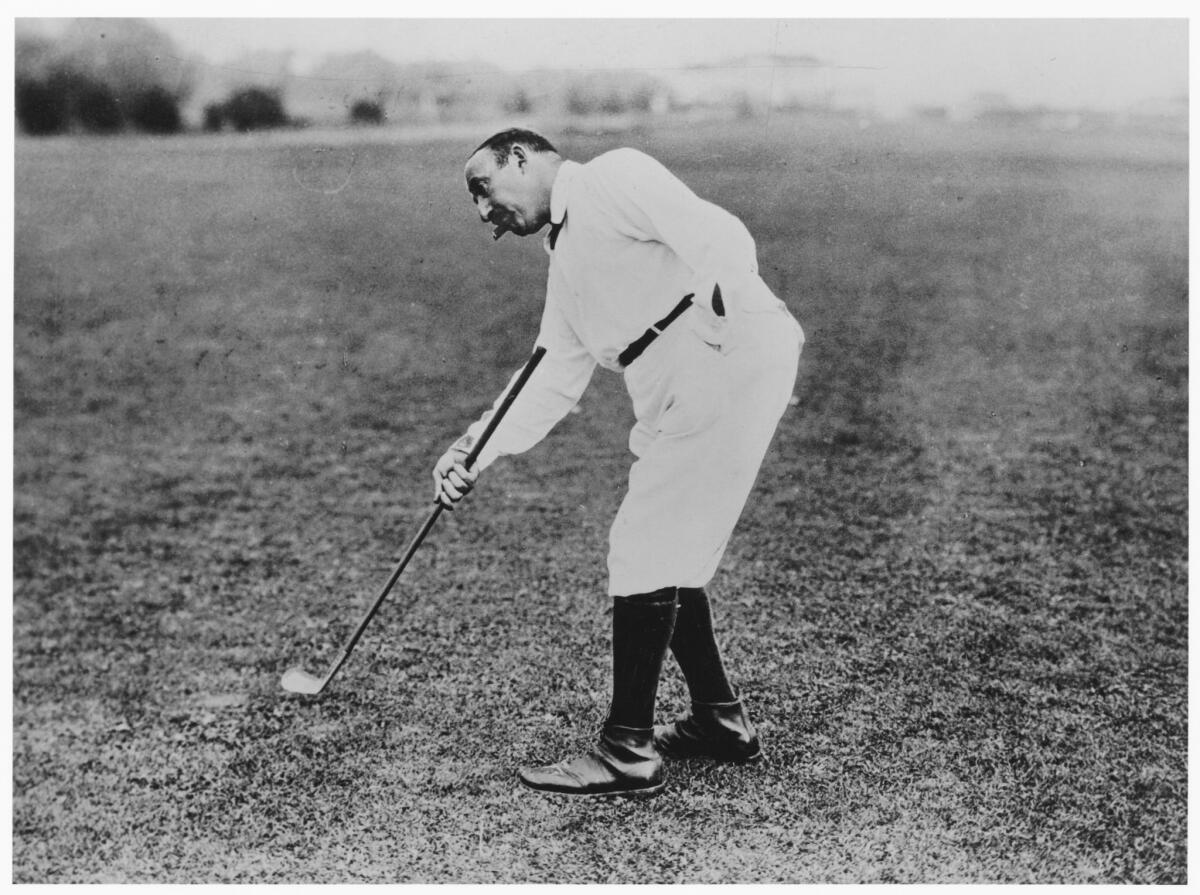

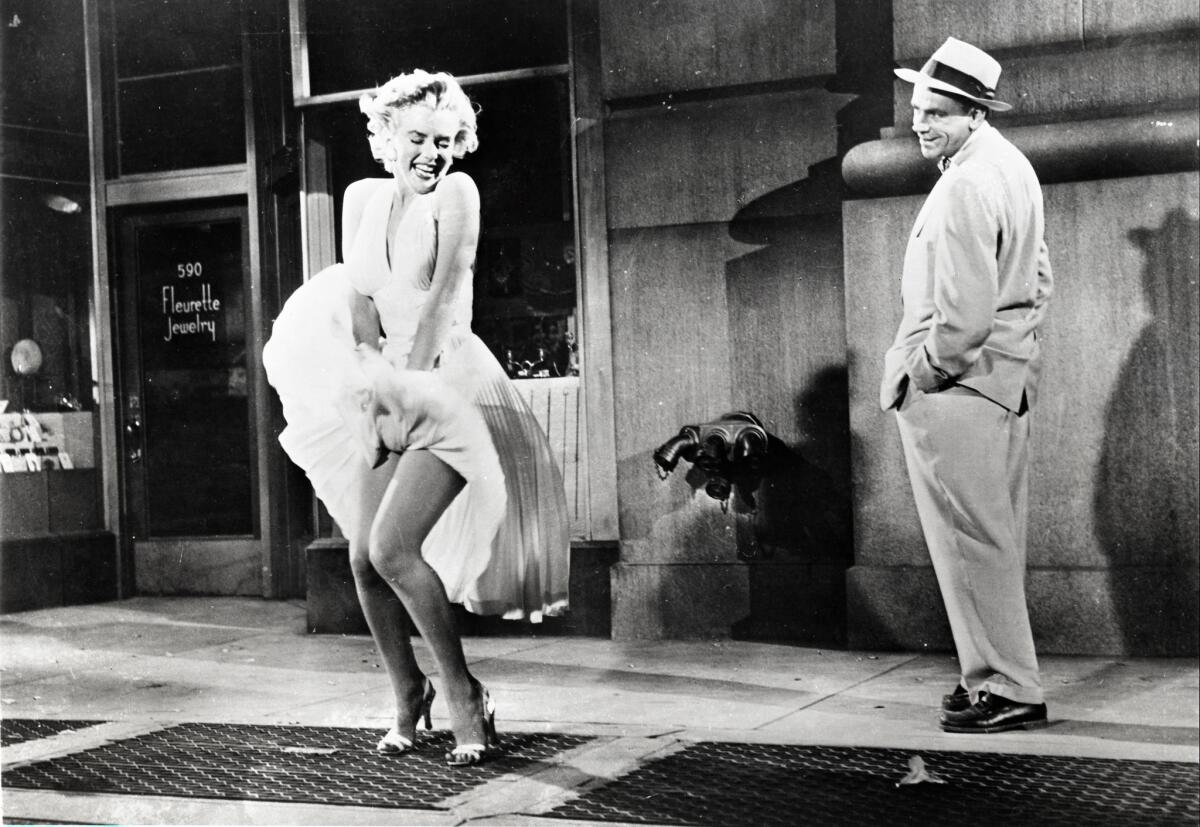

The studio produced some of the highest-grossing films of all time (“Avatar,” “Titanic,” “Star Wars”) and many enduring classics (“The Grapes of Wrath,” “Sound of Music,” “All About Eve”), and it catapulted actors (Shirley Temple, Marilyn Monroe, Will Rogers and Harrison Ford) into box office stars.

Over the years, the studio has been run by several owners and moguls and produced an impressive run of hits and expensive flops (1963’s “Cleopatra,” starring Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton, nearly sank the studio when its original budget of $4 million ballooned to $44 million). It helped pioneer home video, and launched a fourth TV network, cable channels and a boutique film studio churning out a slate of award-winning entertainment.

And then, in December 2017, the Murdoch family, whose company has owned Fox since 1985, agreed to sell Fox’s film and TV operation and several channels to Disney for $71.3 billion. The deal is expected to close in the coming days. Fox will retain ownership of the legendary lot and such businesses as the Fox Broadcasting network, Fox Sports and Fox News. But a chapter in Hollywood history will be over.

The Los Angeles Times spoke to dozens of actors, executives and other Fox veterans to reminisce about the studio’s 106-year legacy, its family atmosphere, its moguls, its filmmakers and the magic they made. Their comments have been edited for brevity and clarity.

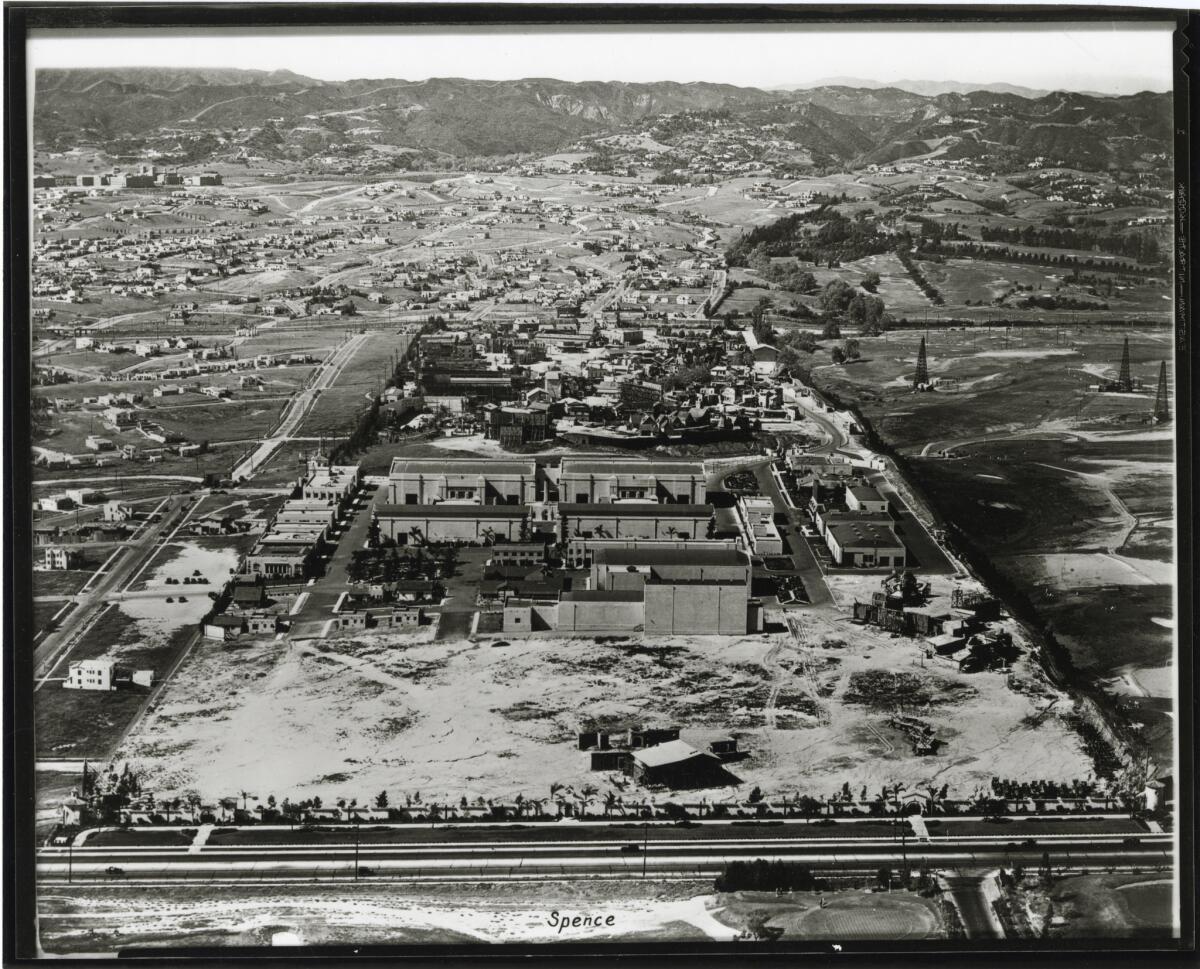

On the lot

The story began in 1915 when William Fox, a Hungarian émigré who owned a clutch of New Jersey nickelodeons, began producing and distributing films. A year later he decamped to Los Angeles and launched the Fox Film Corporation, eventually landing on 100 acres between Santa Monica and Pico boulevards. Fox’s 1926 purchase of Movietone, a company that successfully wedded sound to moving pictures and developed popular newsreels, led him to marvel that the Fox name could be found on screens across the globe. The studio, originally known as Movietone City, opened to great fanfare in October 1928 and was hailed as “the newest, largest, and most completely equipped plant for the production of motion pictures in the world.”

By 1930, however, Fox, who’d borrowed heavily to expand his empire, lost control of the studio. In 1935, Fox Film merged with Twentieth Century Pictures, founded by Joseph Schenk and Darryl F. Zanuck. The newly formed Twentieth Century-Fox ushered in a golden age of westerns, musicals, sweeping epics and the first movie filmed in proprietary CinemaScope, “The Robe.”

Esmé Perry-Trueheart (senior archivist at 21st Century Fox, October 2008 to January 2018): It was one of the best jobs I ever had. The collection goes back to the days of Fox Film and 20th Century Pictures. You are just unearthing these treasures all the time, creating access for film buffs and preserving film history. The Shirley Temple photography included production shots and promotion shots in a file called the “Star-Head.” The contract players had them too. They contained all the publicity shots, and Shirley’s Star-Head took up several boxes. There was a portrait of her playing with her puppies at her bungalow.”

Susan Perkins (“Permanent Temp” 1967-1968, 1973-2008): I started in the script department in 1967, taking dictation. When I turned 40 they wanted me out of the [temp] pool and in a permanent job, but I said no. It was so much more fun to wander. I worked with writers, producers and directors. I went to the backlot. In one year I had 48 jobs. The only department I never wanted was legal. I wanted to be with the creatives.

Marc Wanamaker (film historian and archivist): I was at Los Angeles City College’s music department. I was in a marching band when “Hello Dolly” was casting for extras that would be in the final scenes. The casting people went to area high school and junior colleges’ music departments, they needed 50 drummers. I was one of the drummers. All of the talk among everyone was what an honor to be in this epic film on this historic lot.

John Candreva (executive director, Studio Facilities Operations, 1989 to present): I came here in 1989. None of the fire systems on the lot worked. Factory Mutual, the insurance underwriters, gave them a mandate to fix every fire system on the lot within 30 days or they would lose their insurance. So I got hired to come in by the facilities department. And we basically lived here for 30 days, me and my crew. And we did such a good job they just kept us.

Suzy Mamann-Greenberg (co-executive producer, “How I Met Your Mother,” 2005-14): The lot was just full of movie history. I remember one of the first things I saw going to the soundstage was a “Sound of Music” mural with Julie Andrews. You would see things like this all of the time, but it never got old.

Bill Mechanic (chairman and CEO of Fox Filmed Entertainment, 1993-96): When I got to Fox it was probably the weakest studio or close [to it], and it was sort of in decay; they were considering selling off the property at the time. I had my final meeting with Rupert Murdoch, who was then in the administration building. I thought it would be immaculate. I walked in and the sign said FOX FI Corp. That was the state of the studio; no one fixed it. If you wanted to screen a movie you had to rent it back from Sony. The commissary was decrepit.

John Landgraf (Chief Executive Officer of FX Networks and FX Productions, joined FX in 2004): I am a cinephile, so the legacy of 20th Century Fox is meaningful to me. I love the fact that my office looks out on New York Street. Ryan Murphy’s office is in the building where they painted the scrims, back when we didn't have green screens.

There’s no business like show business

At its peak, the backlot encompassed 285 acres and had a western town, a harbor and Mulberry Street — better known as New York Street, originally built for “Hello Dolly” in 1968. Over the years much of the backlot was sold off, but the 53 remaining acres are drenched in history. What’s left of Sonja Henie’s original ice skating rink is under Stage 15, and James L. Brooks’ offices were once Frank Sinatra’s bungalow, and before that it was Will Rogers’.

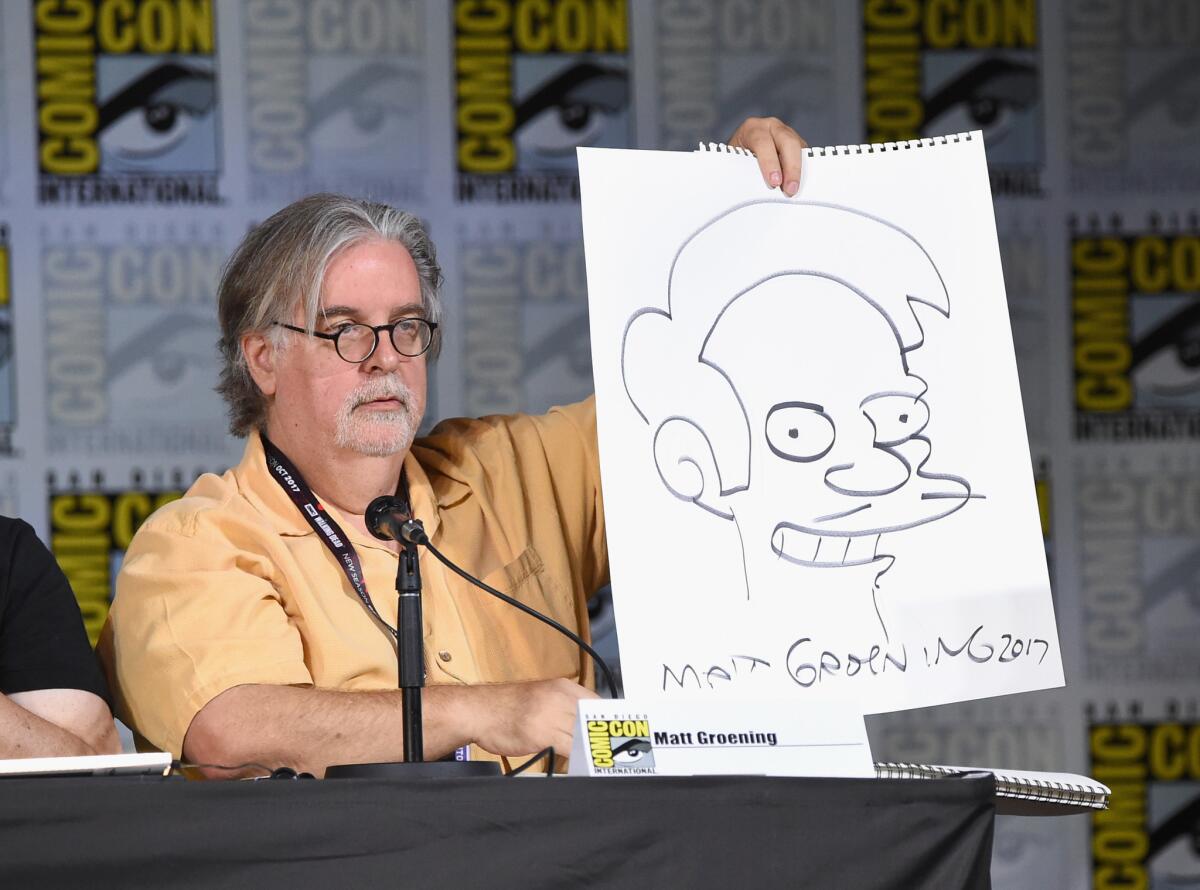

Matt Groening (creator of “The Simpsons,” debuted in 1989):You know, it's really fun to drive on to the Fox lot; it's like an old-fashioned studio lot and you see those giant soundstages. It feels like, “Oh, my God, I'm in Hollywood.”

Schawn Belston (executive VP Media and Library Services, 1996 to the present): The fun part of the job was working with filmmakers. We were going to restore the “Seven Year Itch.” After like the fourth time I called Billy Wilder, his secretary said, “He will never call you back.” I said, “That’s too bad, can you tell me why?” She said, “Yeah, if you want to get a response, write him.” So I wrote him a letter. Then he called. I’ll never forget hearing, “Please hold for Billy Wilder.” He told me, “Do whatever you want. I don’t care for that picture.”

Candreva: Mel Brooks had his office here for years. Fantastic man. Funnier than crap. You could just go in and sit in his office and talk to him. I used to test fire alarms late at night. I'd always do my work at 2 or 3 in the morning, right? And Mel was always in his office. And, boy, he'd call you in and he would bounce jokes off you, and he was a riot.

Perkins: One guy I worked for was the producer Stan Cherry. He asked me for plywood boards to put on his desk. I said, “What do you need those for?” He said, “Tap dancing.” I took dictation while he tap-danced.

The Commissary

In 1930, two of the studio’s biggest stars, Will Rogers and Fifi D’Orsay, opened the Café de Paris. It was built on part of the semi-permanent French restaurant set, hence the name. The studio’s scenic painters created the famous murals of world capitals and Hollywood stars that adorn the walls. During World War II, Berlin was painted over, replaced by Athens in a nod to then studio chief Spyros Skouras. The restaurant still serves an average 225 lunches a day.

Sherry Lansing (former president of 20th Century Fox Studios, 1980-83, the first woman to head a Hollywood movie studio): I remember we had a board meeting in the commissary after Marvin Davis bought the studio. The board was very distinguished. There was former President Gerald Ford, Henry Kissinger and Grace Kelly. Walter Matthau and Jack Lemmon came to the lunch, they must have been filming. We sat at a round table and there was silence, and then Walter said, “President Ford, I have something that I’ve always wanted to ask you.” He said, “Of course, Walter, what is it?” He said, “Could you please pass the cookies?”

Groening: I love going to the classy old Art Deco-style commissary, sitting there and seeing big stars and Fox executives. Rather than bothering people for a meeting, I often just waited in the commissary until somebody I wanted to talk to walked by.

Neil Patrick Harris (actor, starred on “Doogie Howser, MD,” 1989-93 and “How I Met Your Mother,” 2005-14): Oh, the commissary was very exciting. It was a quintessential who’s who of the Hollywood backlot. Producers had certain tables. I remember sitting with Steven Bochco once at lunch and up walked Henry Winkler. He was so effusive and so kind and complimentary and I just couldn’t believe he was so nice. Seeing someone who I literally grew up thinking was the coolest man to have ever been on TV. I mean, the Fonz’s leather jacket is in the Smithsonian; to acknowledge your existence is cool enough, but when he acknowledges your talents too, ayyyy.

Mechanic: I’m a vegetarian and that’s where the veggie burger at the commissary came from, it gave me something I could eat.

Kyle Nelson (Commissary executive chef, 2017 to present): The great thing about this place is that it’s for everybody. We have a very diverse population from the Murdochs on down. On Friday, the backlot guys come in for breakfast and get a NY steak and eggs and a pile of potatoes and it costs $9 or $10 and they’re good for the day. The dining room is not exclusive.

Family business

Long before the Murdochs moved in, Fox was described as a “family,” which was reflected in the collegiality of the lot, the meritocracy of rubbing elbows with everyone on the entertainment spectrum and the number of multi-generational employees who’ve worked at the studio for years.

Jason Perkins (prop maker, 1998 to present): My grandfather ran the mill [in the prop department]. My father ran the mill after that and my brother and I worked on the sticker machine. When the mill closed down, I moved over to the cabinet shop. This studio, it keeps my family employed. [He points to a decades-old photo of a woman during a family day on the lot.] See, I’m in my mom’s stomach right there, so I was even on this lot before I was born. And my wife works here. I met her at a Christmas party. She works in domestic distribution.

Perry-Trueheart: Randy Newman and his son came down, and his uncles [Lionel and Alfred Newman] scored music. We were looking at some photos, and Randy Newman pointed to a man and said, “That’s my dad.”

Danny DeVito (actor, “Romancing the Stone,” and director, “The War of the Roses”): I love going to that lot, it’s just a comfortable place to be. The nice thing, the great thing about it is it’s like a family, tight knit, and once in a while there’ll be a bump in the road and with people you can rely on, it’s a lot easier to navigate them.

The Moguls

From the days of Darryl F. Zanuck, the studio has had a number of colorful studio chiefs that have each made their mark, not just on movies but Hollywood.

Alan Ladd, Jr. (head of creative affairs 1973, president of Fox’s film division 1976-79; green-lit such films as “Alien,” “Star Wars,” “Silent Movie” and “The Rocky Horror Picture Show”): Fortunately, I was in a position where they really let me do what I wanted to do and make pictures I wanted to make. It was not corporate in any way. Quite frankly I don’t think anybody would’ve made “Star Wars” again if it had been by committee. Now it’s become a business of, how much do you think it will make domestically as well as foreign? People are making all kinds of decisions of what to do with films. And I didn’t have that problem. It was a very nice time when I was there.

Michael Gruskoff (producer, “Young Frankenstein,” 1974): One of the biggest tributes to Laddie [Alan Ladd, Jr.] was that he hired female executives: Paula Weinstein, Sherry Lansing and Cheryl Boone Isaacs. I asked him once why the majority of the executives were becoming all female. He said that he discovered on Friday that each executive had scripts to evaluate. He found out on Monday mornings that when he went to discuss the project the female executives had read all five of the scripts while the males maybe read three and the females had made synopses on each one and they were more detailed.

Lansing: When I started, Marvin Davis asked to see the head of the studio and I went in to see him. He said, “No, no, no, honey, I don’t need any coffee.” I said, “No, I’m Sherry Lansing.” He said, “I want to see Jerry Lansing, head of the studio.” I said, “No, I am Sherry Lansing.” He said, “Oh, a girl.” After that he was fine.

Tom Rothman (ran the studio with Jim Gianopulos, 2000-12): I still have somewhere in my files the three-page business plan for running [Fox] Searchlight [founded in 1994]. I typed it up when I was running the Samuel Goldwyn Co., in the heyday when indies were indies. We were all competing with each other on a level playing field, and then one day I woke up and Disney had paid $80 million for Miramax, and I knew the world had changed. But I had an idea, and the idea was that you didn’t have to do that, that you could create within the larger infrastructure of a major studio, an independent aesthetic. If you designed it right, you could have the advantages of a major and the advantages of an indie.

Behind the scenes

Fox’s legacy comprises the many memorable films and TV programs it has produced — but behind every hit is a back story.

Ladd Jr.: I made certain changes to help the chances of [“Alien”] working, making Ripley from male to female. Sigourney [Weaver] was perfect for the role. I don’t know where Ridley [Scott] found her, but she was perfect in it. I was brought up at a certain time during the war years when all the men were out fighting, and women became the stars of those days. I have four daughters too, so I am a little biased, I guess.

Gruskoff: “Young Frankenstein” was originally a Columbia picture, but they turned Mel [Brooks] down after he wanted to do it in black and white, and so we were allowed to take it to Fox. Mel took it to Laddie, and he green-lit the movie.

One of my favorite memories was when the grosses of “Young Frankenstein” came in that first weekend. We went down to see Laddie, and everyone was very happy. All I knew was that it was a fantastic, terrific figure, a beautiful number. We did everything, except we did not jump up and down — we were not children.

DeVito: I was screening “The War of the Roses” with Tom Sherak, the head of marketing at Fox. We were thinking how are we going to sell it? It’s a very dark movie, and he came up with the log line, “Every once in a while a movie comes along that makes you fall in love. This is not that movie.”

Jim Gianopolus (ran Fox film studio from 2000-12 with Tom Rothman): I do remember the decisions about “Titanic” and “Avatar,” especially. “Titanic” was, “Are we seriously making this movie again? Everyone knows how it ends, and it costs how much?” On paper it was not an easy decision until you heard Jim Cameron’s vision for it, and then we read the script, and it seemed a lot easier. Going in, it was a pricey enterprise. It seemed like something you didn’t want to pass up, and it was the same way with “Avatar.” There were times when as the costs mounted, it was not without worry. But just when you got worried, Jim Cameron would show you a few minutes of film and you’d go, “OK, I see what this is going to be, this is going to be incredible.” As you saw the films evolve, you realized they were truly extraordinary and were going to redefine cinema history.

Vicki Snow (head of the costume/wardrobe department, since 1992): They closed and reopened the costume department in the ‘70s when they realized we needed costumes. We got back one of Ethel Merman’s dresses from “There’s No Business Like Show Business” from an auction house. We traded a Keanu Reeves’ shirt from “Speed,” a shirt from Banana Republic, for an Ethel Merman dress.

The thunder from Down Under

Oil man Marvin Davis and financier Marc Rich bought the studio in 1981 for $722 million. By 1985, Rich was a fugitive, and Rupert Murdoch and his News Corp. bought him out for $250 million. Later that year, Murdoch scooped up Davis’ stake for $325 million and quickly put his stamp on the studio.

Gianopulos: Rupert didn’t always love the movie business, but he was incredibly supportive even in the darkest hours of “Titanic” and “Avatar.” He just kept asking, “Will it be great?” And so as much as we were all in fear and trepidation about the size of the budgets involved, he was willing to abide it as long as the outcome was great, and it paid off for him.

Mechanic: On “Fight Club,” Murdoch said to me, “I don’t know what kind of sick human being would make that kind of movie, meaning me, not David [Fincher].” I didn’t say anything.

Dana Walden (chairman and CEO, Fox Television Group, joined Fox in 1992): You would have to go into these meetings [strategy sessions at the end of pilot season] super prepared, and no one likes to be second guessed. But Rupert Murdoch is very instinctive, and he’s a disruptive person. Occasionally, he would go up to the [scheduling] board and move the pieces around, putting a show on a different night, or in a different time slot. You could almost hear a gasp in the room, and he would just laugh. One thing I will miss is the rebellious spirit of the Fox brand.

Gary Newman (chairman and CEO of the Fox Television Group, joined Fox in 1990): In the mid-90s we had a News Corp. retreat at an island that Rupert owned off the coast of Australia. During one leadership session, someone got up and said the company needed an executive committee to oversee the various businesses. People started shouting him down, saying, “We don’t need any stinking executive committee.” We didn’t want bureaucracy to weigh us down.

Stacey Snider (chairman and CEO of 20th Century Fox Film 2016 to present): That was the fun and challenging draw of the place. As long as you could make “Bohemian Rhapsody” for the right price for what the intended audience was meant to be, you could make what we thought was a double or a triple. But if we had to start it by promising it was a home run, we wouldn’t have been able to make it.

Bob Greenblatt (programming executive, Fox Broadcasting 1989-97): He [Rupert] would come in and talk about what shows he liked or that he didn’t like. One of the shows he didn’t like was “Party of Five.” He would be like: “Let’s get rid of it, the ratings are terrible. Let’s get rid of it.” But everyone else was so fervent about keeping the show. We knew it was special, and Rupert never stood in the way of decisions like that. He let us do our jobs.

Peter Chernin (News Corp. president, chief executive of the Fox Group; worked at Fox 1989-2009): It was a culture of enormous excitement. Rupert was fun, he was wild – he wanted to do really bold things. The real story about Fox is that there was a broad, overarching vision and we were allowed to innovate constantly. Rupert created a culture that allowed that.

TV land

In 1986, the company challenged decades of supremacy of ABC, CBS and NBC by launching a fourth network, the Fox Broadcasting Co., with “The Late Show With Joan Rivers.” A year later, the scrappy network kicked off its first night of prime time with the edgy “Married …With Children” and was soon churning out megahits like “The Simpsons,” “The Tracey Ullman Show” and “Beverly Hills 90210,” earning Fox a reputation for distinctive, edgy and youth-oriented fare – and it soared in the ratings.

Ed O’Neill, (actor, starred as Al Bundy on the Fox network’s first hit, “Married … With Children,” and currently stars as Jay Pritchett on the Fox television studio’s hit comedy “Modern Family”): I got a call from my agent, and he said a couple of producers wanted to see me about a show that was going to be on this new network called Fox. Of course, I had never heard of it. I said, “Well, Fox makes movies right?” He said, “Well, they're going to get into the television business.” I said, “Oh, good luck.” They said that it was a pilot called “Married … with Children.” I said, ”Sounds like a horrible name for a show.” Somebody messengered a script over and I read it in the locker room at the Y. I thought it was funny, I thought, ‘Oh, this is never going to go because it's just too raunchy.” There were fat-women jokes, and they made fun of a midget. “It's funny, but it's never going to see the light of day.”

Alan Zweibel (co-creator, writer and producer of “It’s Garry Shandling’s Show,” 1986-90): Garry was doing “It’s Garry Shandling’s Show” on Showtime and no one was watching it. It got the greatest reviews ever and won all sorts of awards, but a lot of places weren’t even wired to get Showtime. A lot of my friends in New York City had to take my word that I created a TV show. Garry was frustrated, everyone knew it was a great show, but there wasn’t a huge audience. When Fox came into existence [and brought Shandling over from Showtime] it was just us and Tracey Ullman on Sunday nights.

Groening: I remember being there [at “The Tracey Ullman Show”] on a Friday night. While they were changing the sets, they put several minutes of Simpsons shorts on the TV monitors. The audience was laughing like crazy. And there was a group of Fox executives who were all huddled together down by the stage. They all slowly turned towards the audience with their mouths open. They could not believe how hard the audience was laughing, and I think that's where the idea to let us do a show on the network came to be.

There would not have been a Simpsons without the Fox network. None of the other major networks would have dared put on a bratty sarcastic animated show like “The Simpsons.”

Dan McDermott (head of current programming at Fox Broadcasting, 1990-95): [Beverly Hills, 90210] became super popular, especially with kids. At the end of the first season, the characters Brenda [Shannen Doherty] and Dylan [Luke Perry] decided that at the junior prom, they were going to lose their virginity. The episode was shot in February. It was done respectfully, you just saw them closing the door to their suite. By the time May rolls around, the season finale airs — and we got the biggest ratings of the year. I arrived at the network and went up to my office. Suddenly, the door opens and it was Barry Diller. I was terrified of Barry, but I thought, “Wow, Barry Diller is going to congratulate me in person.” But no, he said: “You have single-handedly destroyed this show and possibly brought about the destruction of the entire network.”

Mike Darnell (Fox Broadcasting, including as president of alternative programming, 1995-2013; and before that at Fox Channel 11: When I joined Fox it was still considered the maverick network. I was willing to do shows with crazy titles [“When Animals Attack,” “Temptation Island,” “Joe Millionaire,” “The Simple Life”] and wild concepts. And I would take the heat of the critics. We were the only network to put stuff like that on in prime time. It felt like we were the new kid on the block, and they were open to try anything. Controversy was good — there was a boldness to the place.

Seth MacFarlane (actor, creator of “Family Guy” and “The Orville”): There was a Christmas party about seven years ago where a bunch of us after a few drinks said, “How crazy would it be to cap this night off in San Francisco?” So we got on the Fox jet and drove it all the way up the 5. It took 48 hours, but it showed me that Fox will always do whatever it takes to get there.

End of an era

Rumors began swirling in November 2017 that Walt Disney Co. was planning to buy much of Fox’s Los Angeles business. Disney made two bids, the first in December 2017 and a much larger one in June 2018. Shareholders of both companies agreed to the merger in separate ballrooms at the Hilton Hotel in New York City in July 2018.

Snider: I learned about the sale the day it was announced. There was no advance notice. All my colleagues started to look down at our phones. We were in a senior staff meeting, maybe 30 or 40 of us. It got quiet and everyone’s head went down into their phones, and I got called out of the meeting by my assistant to go talk to Lachlan [Murdoch].

Belston: There were rumors for a while, but when it was announced I was surprised. I think I went through the Kubler- Ross, Kessler stages of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance but not in that order. Privately, I thought, well, at least all the “Star Wars” movies will be together.

Landgraf: Until we knew that the rumors of the deal were true, it had never occurred to me that the Murdochs would be sellers rather than buyers. It was just a given around here that that would never happen, so it was quite surprising.

Tomorrowland

With the deal almost done, everyone is anxiously waiting to see how out it will all play out. Fox is in the past. What will the future look like?

Snider: I’m not being coy. I couldn’t even speculate. After the Mueller investigation, there’s been no group more tight-lipped than Disney.

Landgraf: There will be a Fox, but it won’t be the Fox as we have known it.

DeVito: I have high hopes about the future. I think Disney is going to do OK.

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.