What happens when the Internet goes out? This Arizona town found out

- Share via

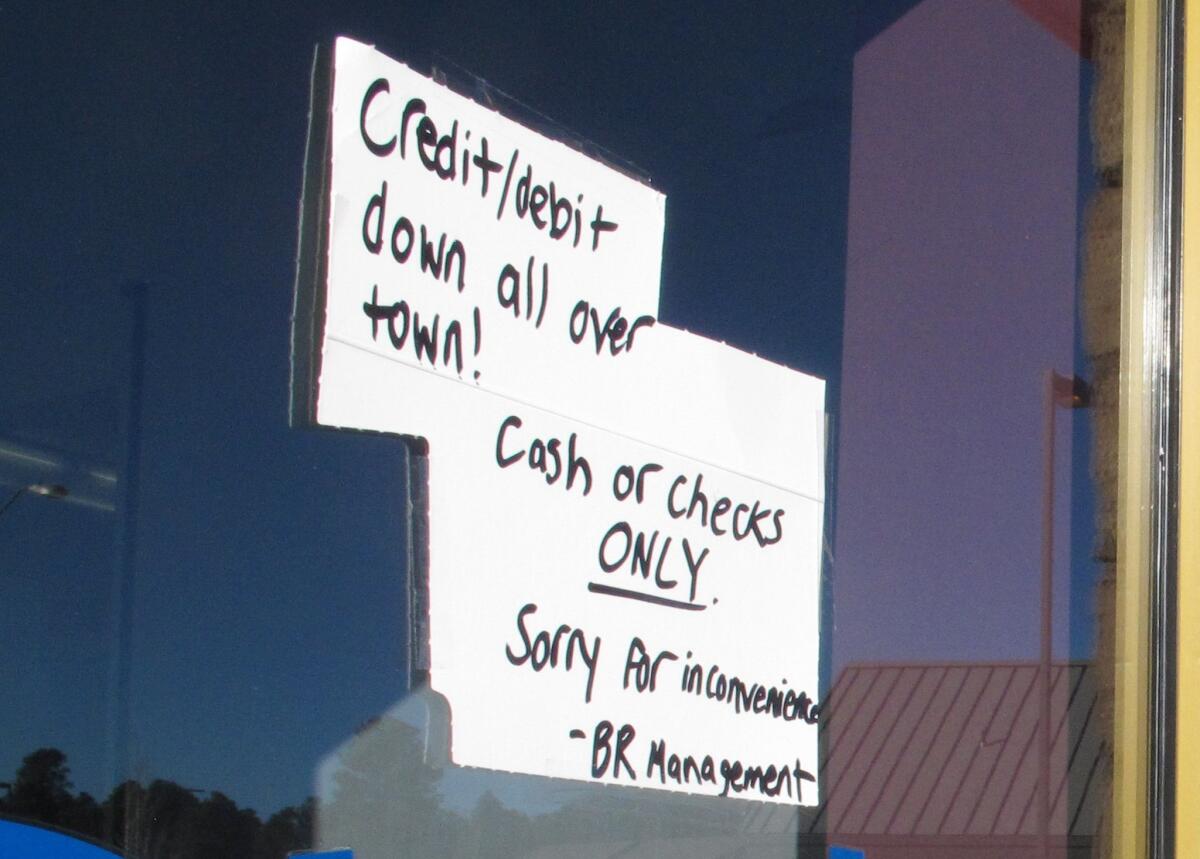

Flagstaff, Ariz. — Computers, cellphones and landlines in Arizona were knocked out of service for hours, ATMs stopped working, 911 systems were disrupted and businesses were unable to process credit card transactions — all because a vandal apparently sliced through a fiber-optic Internet cable buried under the desert.

The Internet outage did more than underscore just how dependent modern society has become on high technology. It raised questions about the vulnerability of the nation’s Internet infrastructure.

Alex Juarez, a spokesman for Internet service provider CenturyLink, said the problem was first reported around noon Wednesday, and complaints immediately began to pour in from customers in an area stretching from the northern edges of Phoenix to cities like Flagstaff, Prescott and Sedona.

Internet and phone service started to come back to some residents and businesses in Flagstaff by 6:30 p.m. and was fully restored by about 3 a.m.

CenturyLink blamed vandalism, and police are investigating.

The severed CenturyLink-owned cable is near a riverbed in a rocky stretch of desert north of Phoenix that isn’t easily accessible to vehicles. It carries signals for various cellphone, TV and Internet providers that serve northern Arizona.

Workers in hardhats could be seen digging up and splicing the cables, which appeared to be bundled in a jacket a few inches in diameter and buried several feet under the rocky soil.

CenturyLink gave no estimate on how many people were affected.

As the outage spread, CenturyLink technicians began the long, tedious process of inspecting the line mile by mile. They eventually located the severed cable and patched it back together.

Meanwhile, Flagstaff’s 69,000 residents tried to go about their daily business.

Zak Holland, who works at a computer store at Northern Arizona University, said distraught students were nearly in tears when he said nothing could be done to restore their Internet connection.

“It just goes to show how dependent we are on the Internet when it disappears,” he said.

Many students told Holland they needed to get online to finish school assignments. University spokesman Tom Bauer said it was up to individual professors to decide how to handle late assignments.

Kate Hance and Jessie Hutchison stopped at a Wells Fargo ATM to get cash because an ice cream shop couldn’t take credit cards without a data connection. They left empty-handed because the outage also put cash machines out of service.

“It’s moderately annoying, but it’s not going to ruin my day,” Hutchison said.

Mark Goldstein, secretary for the Arizona Telecommunications and Information Council, said CenturyLink’s cable probably has bundles of fibers that can be leased to multiple service providers. If there is no alternative path, damage to the line will wreak havoc, he said.

At Flagstaff City Hall, employees were unable make or receive calls at their desks. The city relied on the Arizona Department of Public Safety for help in dispatching police and firefighters.

In Prescott Valley, about 75 miles north of Phoenix, authorities said 911 service was being supplemented with hand-held radios and alternate phone numbers.

Yavapai County spokesman Dwight D’Evelyn said authorities couldn’t get access to law enforcement databases either.

Weather reports from the region weren’t able to reach anyone. During evening newscasts, Phoenix TV stations showed blank spaces on their weather maps where local temperatures would normally appear.

ALSO:

Editorial: FCC poised to favor Internet users over service providers

Pew: Most Americans say Internet makes them feel ‘better informed’

Review Andrew Keen rages against the machine in ‘The Internet Is Not the Answer’

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.