Executives coached coroners on how to keep body parts harvesting records secret

- Share via

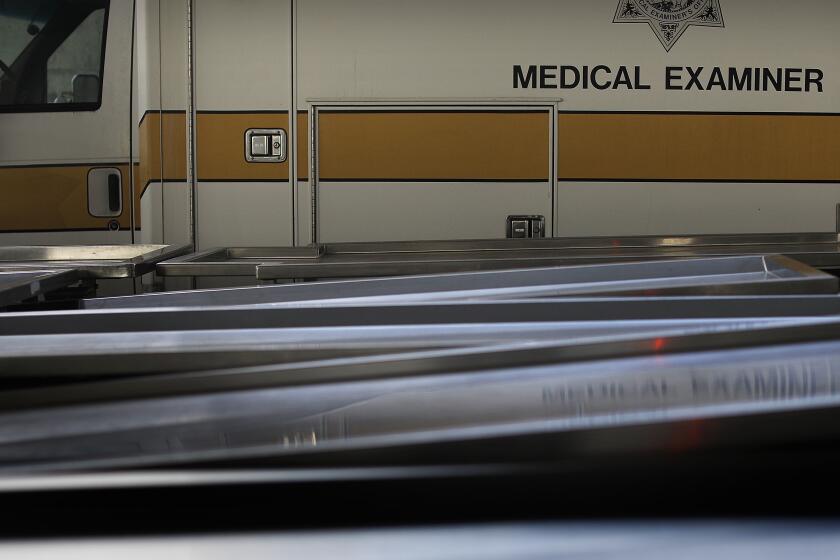

When the Los Angeles Times asked for details of the human tissue procurement industry’s operations inside five large California county morgues, public officials worked with corporate executives to keep the activities secret, according to internal government emails.

At a convention of California county coroners in September 2017, the companies’ executives discussed filing a lawsuit to block the release of information that reporters had requested under California‘s public records law. The companies later decided against the lawsuit, according to an executive’s email, because of fears it would spark controversy.

“They have decided not to pursue that course of action because they believe doing so will raise large red flags,” the executive from Sierra Donor Services, a large procurement company, said in an email to Sacramento County Coroner Kimberly Gin in October 2017.

For decades, California courts have considered autopsy reports and coroner records to be public information. The Los Angeles County coroner has for years given The Times data on deaths it investigates.

Yet when officials saw that reporters were looking at the increasing number of cases in which companies procured tissues or organs before the government’s autopsies of possible homicides and other unexpected deaths, the morgues blocked access to the records.

To report this series of stories, reporters instead turned to coroner data that L.A. and San Diego counties had previously provided to The Times and the Union-Tribune. The newspapers have used the data for myriad stories. By searching the data, reporters found hundreds of cases in which companies procured organs or tissues before the autopsy.

Reporters then asked for the autopsy reports in those cases, finding more than two dozen investigations that were hampered by the harvesting of body parts or actions of the procurement companies.

The Times sent its first request for documents related to coroner cases in which tissues were harvested to the L.A. County coroner in late June 2017. According to emails, coroner officials soon called OneLegacy, a company that procures organs and tissues from the deceased in Los Angeles and six other Southern California counties.

OneLegacy then organized a July 5 conference call involving its executives and L.A. County officials. Also on the call, according to the emails, was Christina Strong, a New Jersey lawyer who has long worked for the nation’s human tissue procurement industry.

In an Aug. 2, 2017, email, Prasad Garimella, OneLegacy’s chief operating officer, alerted executives at the three other procurement companies in California that The Times had requested information about the procurement of body parts in the L.A. County morgue.

“It has been the county’s practice to say no the first time and if the reporters are persistent, then they will issue a limited amount of info,” Garimella wrote to the other executives.

Garimella added that OneLegacy had similarly “guided” L.A. County coroner officials when they received a request for documents from a reporter from CBS in 2011. He wrote that OneLegacy had given coroner officials legal language to use in a letter denying the reporter’s request. He said he was forwarding that letter to the other companies’ executives “so we all can get on the same page.”

Besides L.A. and San Diego counties, The Times asked for records from morgues in Orange, Sacramento and Riverside counties. All five refused to provide a list of deaths investigated by coroners, including names of the deceased, in which the companies had procured body parts.

Later, reporters requested the internal government emails.

Emails from officials in Sacramento, Orange and L.A. counties detail how they updated one another as they denied the newspaper’s requests.

“What verbiage do we need to jettison/refuse this request?” one employee in the Orange County coroner’s office wrote to another.

Former staff writer Gus Garcia-Roberts contributed substantial reporting to this story before his departure from The Times in 2018.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.