NoMad hotel joins crop of boutique inns giving second life to L.A.’s historic office buildings

- Share via

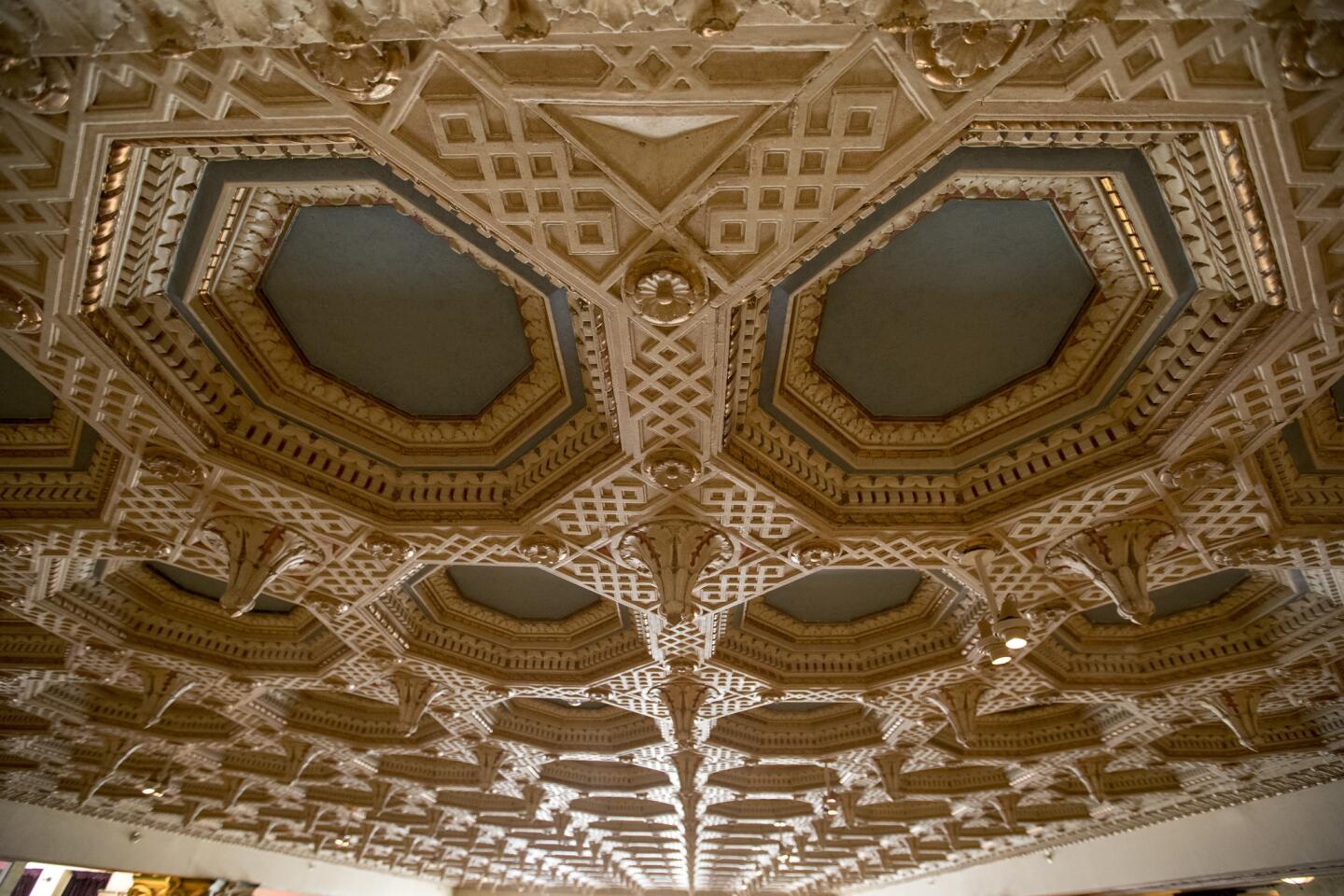

The Bank of Italy once owned one of the finest office buildings in downtown Los Angeles, a 12-story neoclassical monument built in 1923 with towering Doric columns, an ornate, gold-ceilinged lobby and marble floors.

By the late 20th century, however, it had fallen into neglect and for several years it was a shuttered eyesore — before reopening in January as the ritzy NoMad hotel, where rooms typically cost more than $400 a night.

In its most elegant restaurant, guests seated on a mezzanine overlooking the grand old bank lobby dine on foie gras, suckling pig and black truffle tartes.

The return to glory of the temple of finance created by pioneering California banker A.P. Giannini at 7th and Olive streets reflects the economic comeback of downtown and the rush to provide a unique kind of lodging for a new wave of visitors drawn to the reviving city center.

These days, older office buildings are particularly prized by operators of personality-laden boutique hotels intended to appeal to travelers who shun the well-known chain brands that dominate the hospitality industry.

“I love great architecture,” said billionaire investor Ron Burkle, who had his eye on Giannini’s former Southern California headquarters for a long time before buying it in 2015 to turn into a hotel.

Raised in Los Angeles, Burkle said he used to mourn how the city’s historic buildings fell out of favor in the latter decades of the 20th century as businesses left them behind in favor of new towers on Bunker Hill and near the Harbor Freeway.

“People jumped over everything they already had and built a new city,” Burkle said. “I thought it was sad. Now, thank God they did.”

Operators of downtown hotels such as the NoMad, Freehand and Ace draw on the character of city landmark buildings erected nearly a century ago to create a sense of history and mystique in their modern inns.

The Standard Hotel, created out of a former 1950s office building in the financial district in 2002, proved that young, hip travelers looking for a bargain would stay downtown and that a rooftop bar could sell oceans of alcohol.

But it was the quick success of the trendy Ace Hotel Los Angeles that opened in 2014 on a forlorn stretch of Broadway that galvanized investors. The theater and office complex-turned hotel built in 1927 by United Artists founders Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, Charlie Chaplin and D.W. Griffith drew a sophisticated crowd willing to spend lavishly on rooms, food and drinks.

The developers who bought the run-down building for $11 million in 2011 sold it as the Ace Hotel for $103 million in 2015 after spending an undisclosed amount on renovations. Its appeal as a lodging and entertainment destination for tourists and locals alike encouraged investment in the blocks nearby.

On Broadway near the Ace, the boutique Hoxton and Downtown L.A. Proper hotels are being created by separate developers in brick-clad towers dating to the 1920s.

Another boutique on the way is Hotel Figueroa near L.A. Live, set to reopen this month after a multimillion-dollar makeover meant to lift the 1920s-vintage inn from down-market to deluxe — rooms are listed at more than $400 a night.

“An older building gives you a lot of cues and signals about what it wants to be,” New York hotelier Andrew Zobler said. “It gives you a story.”

Then it’s up to the developer, architects and interior designers to tell a story that potential guests will buy into. Not just any old building will do.

Zobler, founder of boutique hotel chain Sydell Group, had already renovated old structures into new hotels in New York, Miami and L.A.’s Koreatown when he and his partner Burkle began looking for properties in downtown Los Angeles a few years ago.

Burkle, who owns the biggest stake in the Los Angeles buildings Sydell Group operates as hotels, helped snatch up the vacant Commercial Exchange Building at 8th and Olive streets for nearly $16 million when it came on the market in 2014.

It was only a block away from the Giannini building Burkle had long coveted. Giannini Place wasn’t for sale, but Burkle and Zobler persuaded the owner to sell it for more than $39 million.

Then came the hard part: turning the two beaten-down office buildings into luxurious inns with hundreds of bathrooms, elaborate restaurants and rooftop swimming pools with chic bars where patrons can sip evening cocktails in the glow of city lights.

Zobler decided that the former Commercial Exchange Building he called “gritty and humble” felt more like a Freehand, Sydell Group’s young-skewing, less-expensive brand. About a third of the rooms are communal, where guests can sleep on a bunk bed for as little as $40 a night.

“It’s a hotel with the spirit of a hostel,” Zobler said.”We wanted to create a place that was kind of communal, where you want to meet other people who are there.”

The more glamorous Giannini building would be a NoMad, the developer’s upscale brand, with handsome finishes and food service by New York restaurateur Will Guidara and award-winning Swiss chef Daniel Humm.

The NoMad’s design theme is California-meets-Northern Italian, Zobler said, including a Venetian-style coffee bar where patrons drink standing up.

The massive vault door on the underground level where Giannini placed 12,000 safety deposit boxes now leads to restrooms. Bank of Italy, which became Bank of America, was one of the first to cater to women and working people turned away by other banks.

Recent conversions of older structures such as offices to hotels reflects a second wave of adaptive reuse in downtown Los Angeles, architect John Arnold said.

It follows the first wave that started around 2000, when historic commercial buildings began being turned into housing following the adoption of a city ordinance meant to encourage such transformations.

“The buildings we are seeing turned to hotels now were passed over in that era,” said Arnold, whose firm, KFA, oversaw the makeovers of the Freehand, NoMad and several other old downtown buildings.

The narrow Freehand structure, with its small, film-noirish “Sam Spade”-style offices, was more easily converted to hotel rooms than loft-style apartments, Arnold said. Original hallways and transom windows above the doors became part of the hotel.

The vast lobby at the NoMad, where bank tellers once cashed paychecks, would have been impractically large for a residential building, but works as an inviting space for the hotel.

“Now it’s one great living room,” Arnold said.

Repurposing older buildings usually costs less than building new ones, but the renovation route still presents financial risks. The makeovers of the Freehand and NoMad buildings ended up costing more than $200 million, including acquisition costs, Zobler said.

“The disadvantage is that you don’t know what’s behind the walls,” he said.

The foundation of the Freehand was unusually problematic, for example. City officials decided to widen Olive Street in the mid-1930s, and the owners of the building were obligated to reduce the footprint of the 13-story structure by nearly 10 feet.

Engineers chose to cut a 10-foot chunk out of the middle of the building from top to bottom and reunited the building by sliding the western portion east on rails, thereby opening up more space on Olive Street. The process cost $60,000, The Times reported in 1935.

When the Freehand renovation got underway, builders encountered a second foundation that had been poured in over the original in the 1930s project, which created challenges as they worked to attain modern seismic standards. They also found the railroad rails used to move the divided building back together.

Sometimes builders get good surprises when they rip off wall coverings and other “improvements” added through the years. At the Freehand, they unveiled marble walls and old-fashioned transom windows along 7th and Olive streets.

Owl Drug Co. was once located in the building, and flooring was lifted in what is now a restaurant to reveal an owl insignia made of tile. The owl has become a logo for the hotel.

Demand for hotel rooms in downtown Los Angeles has grown with its economic comeback over the past several years, said Jeff Lugosi, managing director of CBRE Hotels Consulting.

The average daily room rate for full-service hotels rose 1.7% last year over 2016 to $233 and average occupancy rose 2.3% to 79%, he said.

Most of the market belongs to big brands such as Marriott, InterContinental and Sheraton, Lugosi said. A Park Hyatt is set to open next year near Staples Center. Competition from older buildings is also arriving.

“Now there are these independent boutique hotels,” he said. “It’s a segment we really didn’t have before.”

Travelers in creative businesses such as entertainment and fashion who might have stayed in individualistic hotels in West Hollywood or Hollywood in the past are now coming downtown, Lugosi said.

These days they may have friends who live downtown. New bars, restaurants and other attractions such as the Broad museum have helped make the neighborhood an overnight option, he said.

Boutique hotels appeal to the self-image of many creative types, Lugosi said. Burkle sees even wider appeal in their competition with big traditional brands.

“The NoMad has an Old World feeling with youthfulness to it,” Burkle said. “The Four Seasons is where your parents would stay — even if you’re in your 70s.”

Twitter: @rogervincent

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.