Chicago hopes Zell polishes civic icon

- Share via

CHICAGO — For more than 40 years, Martha Campbell has started her day by picking up a copy of the Chicago Tribune.

As a youngster, she scoured the pages to make sure the country hadn’t gone to war with the Soviet Union. As a parent, she got up hours before her three children woke to study the opinion pages and read the feature stories. Now, as a retiree, she turns to the crossword puzzle -- and also sadly tracks the stories about her beloved hometown paper’s fading fortunes.

“When I heard that Sam Zell was buying the Tribune, I actually felt a spark of hope,” said Campbell, 61, a former consultant for a relocation firm who lives in the Chicago suburb of Highland Park.

“He’s a local. He’s successful. And I can’t imagine that he’s going to want such a huge Chicago institution to fail.”

The $8.2-billion privatization deal gives Zell control over one of the nation’s largest broadcast and newspaper companies. Tribune’s holdings include the Los Angeles Times, cable TV network Superstation WGN and nearly 30 other television stations, radio outlets and newspapers.

And, of course, the Chicago Tribune.

As a chapter in the Windy City’s corporate annals comes to an end, much of the chatter among local residents and business leaders revolves around the same questions.

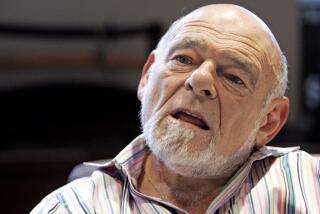

Can a motorcycle-riding, suit-shunning, profanity-loving billionaire -- a man whose public persona seems to hark back to the days of legendary Tribune newspaper baron Col. Robert R. McCormick -- do better than the exiting corporate stewards?

Can Zell save the company from extinction? And if he can’t, how deep will the repercussions be in the nation’s third-largest city?

“This is not just a newspaper. It’s an important corporate donor and fundraiser. It’s a baseball team. It’s a beloved architectural icon,” said James N. Alexander, an Evanston, Ill., philanthropy consultant. “The Tribune Co. is a piece of this city’s fabric and has been for decades. To lose it would be to lose a piece of Chicago.”

At a time when the newspaper industry is consolidating, and two-paper towns such as Cincinnati are losing their afternoon voices, newsprint remains a thriving part of Windy City life. Paper bins and newsstands fill downtown streets. Commuters in the sprawling public transit systems often cram into buses and trains armed with stacks of papers and magazines to read and chat about.

Decades ago, competition among the dailies was so intense that they would hijack rival delivery trucks and dump newspaper bundles into the Chicago River. The men who headed the Chicago Tribune often were considered equal parts visionary and maverick, keeping track of local happenings by tapping into the city’s country club elite and its gritty underground circles.

William Donald Maxwell, a longtime newsman and former editor of the paper, would have his driver take him around the city at night, stopping in bars and South Side hangouts to get a sense of what was happening on the street.

Clayton Kirkpatrick would privately meet with members of the Chicago mob who were causing problems for the paper or reporters covering their criminal enterprises, said Don H. Reuben, the Tribune’s chief attorney from 1954 through the late 1980s.

One Tribune editor, the remarkable Col. McCormick, was arguably as powerful -- and as vilified -- as the politicians who ran City Hall.

McCormick used the paper’s pages to rail against the British and President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and fiercely defend the newspaper’s right to publish free of government restraint. He stood against the U.S. fighting Nazi Germany, challenged the existence of one of the 13 original colonies -- Rhode Island -- and altered the English language so that certain words were phonetically spelled. Freight became “frate” and although was shortened into “altho.”

“But the city’s changed, and so have the rules in the newspaper industry,” Reuben said. “What’s most necessary to the paper is to survive. . . . And Mr. Zell’s an expert in survival.”

Some residents hope Zell is motivated by his reputed loyalty to a town that’s long been his home -- and where his office sits in the old Daily News building, overlooking the river.

They wonder if the paper’s rich history will have a better chance of being preserved by one of their own, particularly at a time when so many of Chicago’s corporate icons have shut down or been acquired by outsiders.

Diners fondly reminisce about the German fare at the Berghoff restaurant, known for getting the city’s first post-Prohibition liquor license. It closed in 2005. Many residents still mourn the passing of the Marshall Field’s brand, with protesters occasionally gathering in front of the department store’s former downtown jewel, which is now a Macy’s. Charities have nervously looked on as LaSalle Bank, renowned for its high-profile local philanthropic efforts, was recently acquired by North Carolina-based Bank of America.

At a news conference Thursday, Zell said he planned for the Tribune to continue supporting its “historic community activities . . . and to do whatever is possible to maintain” that charitable involvement in the future.

So as the biting winter wind cuts through the streets, the Zell-Tribune talk is about more than just the fate of a paper with slumping circulation and dwindling ad revenue.

With Zell’s reputation for savvy real estate deals, gossips wonder if the gothic Tribune Tower building -- long a proud symbol of distinctive architecture and journalism -- might someday be converted into luxury condominiums.

As it is, the Chicago Cubs, the town’s beloved -- and legendarily cursed -- ballclub, has been put up for sale. This month, Tribune executives and Illinois officials said they had held preliminary talks about a possible sale of Wrigley Field to the state agency that owns and runs U.S. Cellular Field, the home of the crosstown rival White Sox. Also up for discussion: selling the naming rights to Wrigley Field.

For devoted readers like Janet Diederichs, the hope is that the newspaper will live long and prosper.

“I’m pretty sure the Tribune will survive my lifetime,” said Diederichs, 78, whose late father, J. Howard Wood, was the paper’s business editor during the Depression and later became publisher. “But is it going to survive beyond that?”

On Thursday, when the news broke that the deal had closed, the hope began to grow.

“I’m sick and tired of people sitting around and talking about the end of newspapers,” Zell said at the news conference. “In the end, this is a business, and my goal is to run it like a business.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.