Where and how the Zoot Suit Riots swept across L.A.

- Share via

Eighty years ago this month, Los Angeles was engulfed in the lawlessness and violence that became known as the Zoot Suit Riots. The name is misleading because it suggests that the zoot suiters — the young Mexican, Black and Filipino men and boys who wore the flamboyant outfits — were the perpetrators. In fact, they were the victims.

The attacks by servicemen and white Angelenos on zoot suiters, derided as “gamin dandies” in The Times, were driven by prejudice and the anti-immigrant attitudes of the era. The roots of the unrest can be traced to events that occurred more than a year earlier — the murder of a young man and the incarceration of Japanese Americans after Pearl Harbor.

Here’s how the violence started, and where it spread.

Showing Places

Feb. 19, 1942: Santa Anita Assembly Center

Arcadia L.A. History

(Associated Press)

Two months after the Japanese Empire attacked Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signs an executive order allowing the government to forcibly move anyone of Japanese ancestry, including American citizens, into incarceration camps.

The Santa Anita racetrack is used as an “assembly center” to hold Japanese Americans. Above, as military policeman watches, a boy in San Francisco sits atop luggage packed for the trip to one of 12 assembly centers in California.

Roosevelt’s order reflected the heightened xenophobia of the time, particularly on the West Coast, where many Japanese Americans lived. More than 120,000 people of Japanese descent were incarcerated in the camps.

The Santa Anita racetrack is used as an “assembly center” to hold Japanese Americans. Above, as military policeman watches, a boy in San Francisco sits atop luggage packed for the trip to one of 12 assembly centers in California.

Roosevelt’s order reflected the heightened xenophobia of the time, particularly on the West Coast, where many Japanese Americans lived. More than 120,000 people of Japanese descent were incarcerated in the camps.

Show more Show less

Route Details

April 8, 1942: Burton’s Smart Clothes

Los Angeles L.A. History

(Associated Press)

The War Production Board sets limits on wool and other fabrics for war rationing.

One of the most popular clothing trends among youths at the time was the zoot suit, which required a lot of material to assemble. The suit was distinguished by a long, drapy coat, billowy pants and a large hat, often topped with a feather. Many people viewed those who wore zoot suits during the war as “un-American,” even if they owned the suits before rationing. In L.A., they were particularly popular among Mexican American, Filipino and Black young men.

Burton’s Smart Clothes in downtown L.A. was one of the stores that sold customized zoot suits.

One of the most popular clothing trends among youths at the time was the zoot suit, which required a lot of material to assemble. The suit was distinguished by a long, drapy coat, billowy pants and a large hat, often topped with a feather. Many people viewed those who wore zoot suits during the war as “un-American,” even if they owned the suits before rationing. In L.A., they were particularly popular among Mexican American, Filipino and Black young men.

Burton’s Smart Clothes in downtown L.A. was one of the stores that sold customized zoot suits.

Show more Show less

Route Details

Aug. 2, 1942: Sleepy Lagoon

Bell L.A. History

(Los Angeles Times)

Jose Diaz, 22, is found unconscious, beaten and stabbed on the shore of a local swimming hole named after a popular swing jazz song, Sleepy Lagoon.

The night before, Diaz had been a guest at a party thrown by the Delgadillo family at the nearby Williams Ranch, where about 40 people danced to a four-person orchestra.

Eleanor Delgadillo Coronado, one of the party hosts, said the last time she saw Diaz at the party he was uninjured. Many of the attendees recalled a large fight that broke out when a group crashed the party later that night. The Times describes the uninvited group as “nine boys” and “three hoodlum girls.”

The fight leaves Joe Manfredi and Cruz Reyes, Delgadillo Coronado’s brother-in-law, with stab wounds to the abdomen. Delgadillo Coronado and her father also are badly beaten.

In its first story about the fight, The Times describes Sleepy Lagoon as “the Consolidated Rock Co.’s gravel pit pool.” At the time, public pools were segregated — barring Black people, Mexicans and Asians—so youths used the pit as a swimming hole.

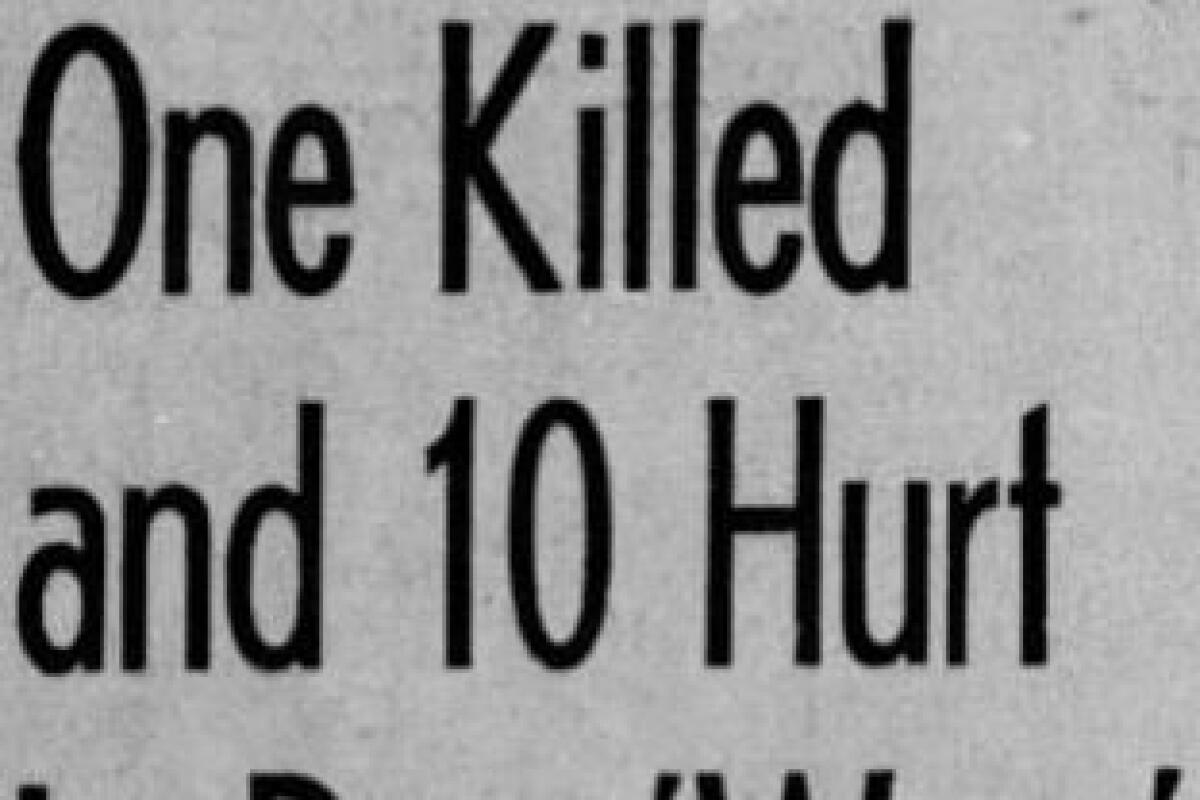

Above, the Times headline for a story: “One Killed and 10 Hurt in Boy ‘Wars.’”

Note: This is an estimated location of Sleepy Lagoon from a hand-drawn map that was provided to author Eduardo Obregón Pagán by Diaz’s brother, Lino Diaz.

The night before, Diaz had been a guest at a party thrown by the Delgadillo family at the nearby Williams Ranch, where about 40 people danced to a four-person orchestra.

Eleanor Delgadillo Coronado, one of the party hosts, said the last time she saw Diaz at the party he was uninjured. Many of the attendees recalled a large fight that broke out when a group crashed the party later that night. The Times describes the uninvited group as “nine boys” and “three hoodlum girls.”

The fight leaves Joe Manfredi and Cruz Reyes, Delgadillo Coronado’s brother-in-law, with stab wounds to the abdomen. Delgadillo Coronado and her father also are badly beaten.

In its first story about the fight, The Times describes Sleepy Lagoon as “the Consolidated Rock Co.’s gravel pit pool.” At the time, public pools were segregated — barring Black people, Mexicans and Asians—so youths used the pit as a swimming hole.

Above, the Times headline for a story: “One Killed and 10 Hurt in Boy ‘Wars.’”

Note: This is an estimated location of Sleepy Lagoon from a hand-drawn map that was provided to author Eduardo Obregón Pagán by Diaz’s brother, Lino Diaz.

Show more Show less

Route Details

Aug. 2, 1942: Los Angeles County General Hospital

Boyle Heights L.A. History

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

Diaz dies from his injuries. He’d been stabbed twice and beaten about the head, coroner investigators said.

The Times reports that Deputy Dist. Atty. V.L. Ferguson announced that a grand jury would “investigate every case which appears to be a manifestation of boy-gang violence.”

Diaz had joined the Army and had been awaiting deployment.

The Times reports that Deputy Dist. Atty. V.L. Ferguson announced that a grand jury would “investigate every case which appears to be a manifestation of boy-gang violence.”

Diaz had joined the Army and had been awaiting deployment.

Show more Show less

Route Details

Aug. 4, 1942: Sheriff's Department Firestone substation

Florence-Firestone L.A. History

(Ray Graham / Los Angeles Times)

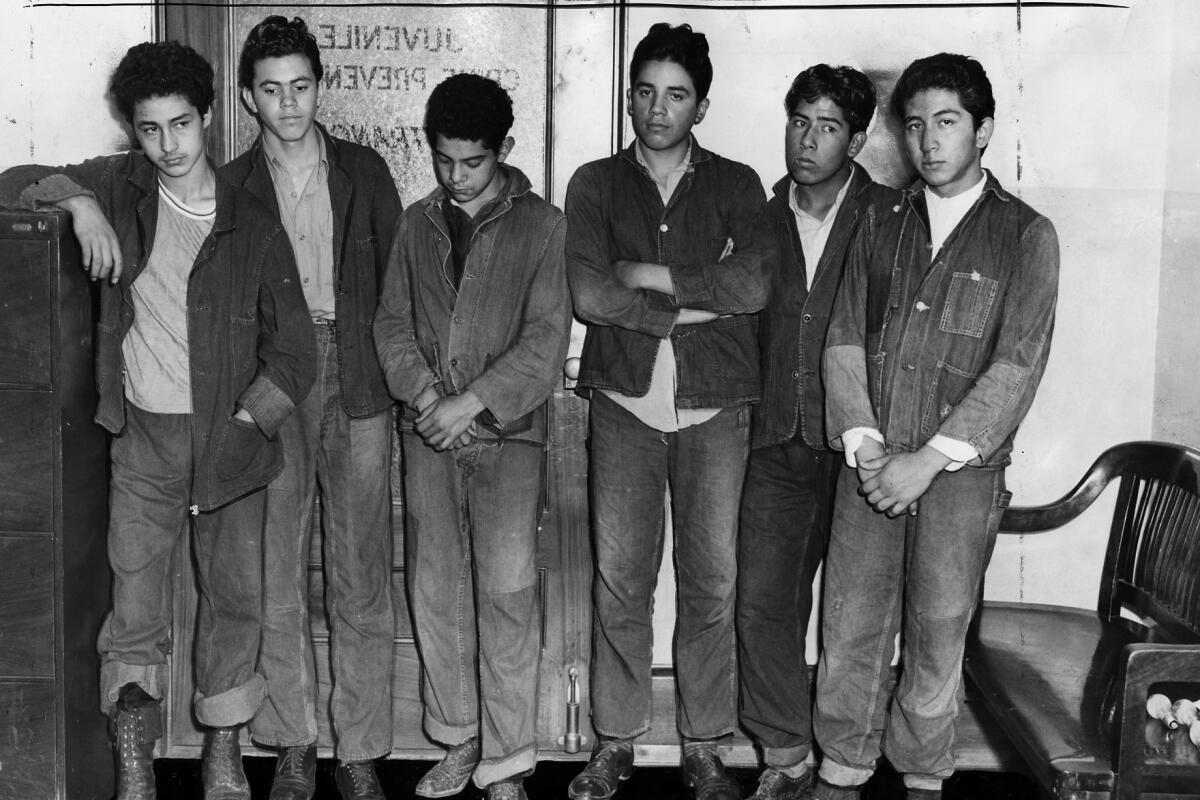

Authorities question hundreds of Mexican Americans from the East L.A. area, accusing many of being members of the 38th Street gang with involvement in Diaz’s death.

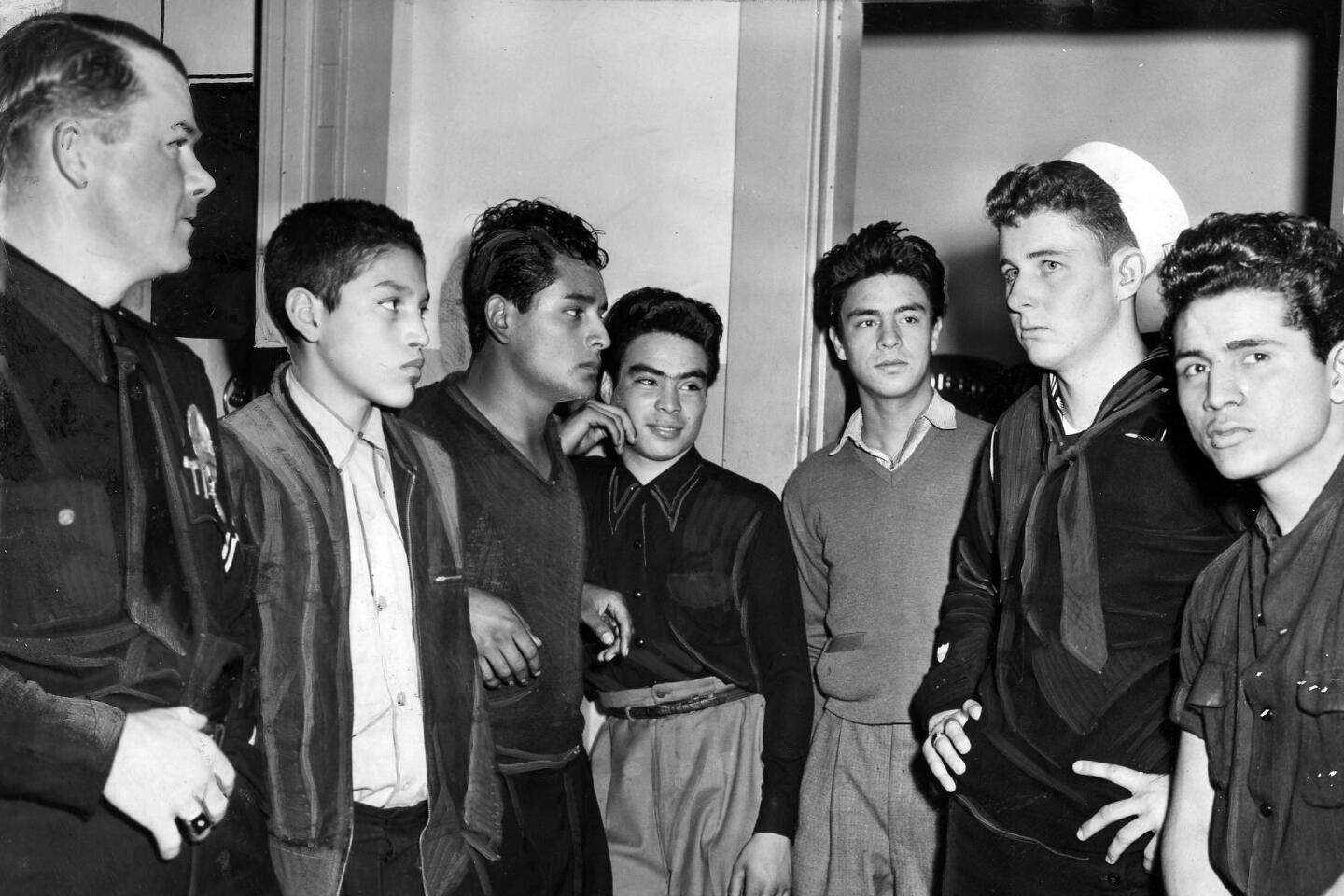

Above, three 16-year-olds and three 17-year-olds are among those detained by police.

Above, three 16-year-olds and three 17-year-olds are among those detained by police.

Route Details

Aug. 5, 1942: Los Angeles County Jail

Chinatown L.A. History

(Los Angeles Times)

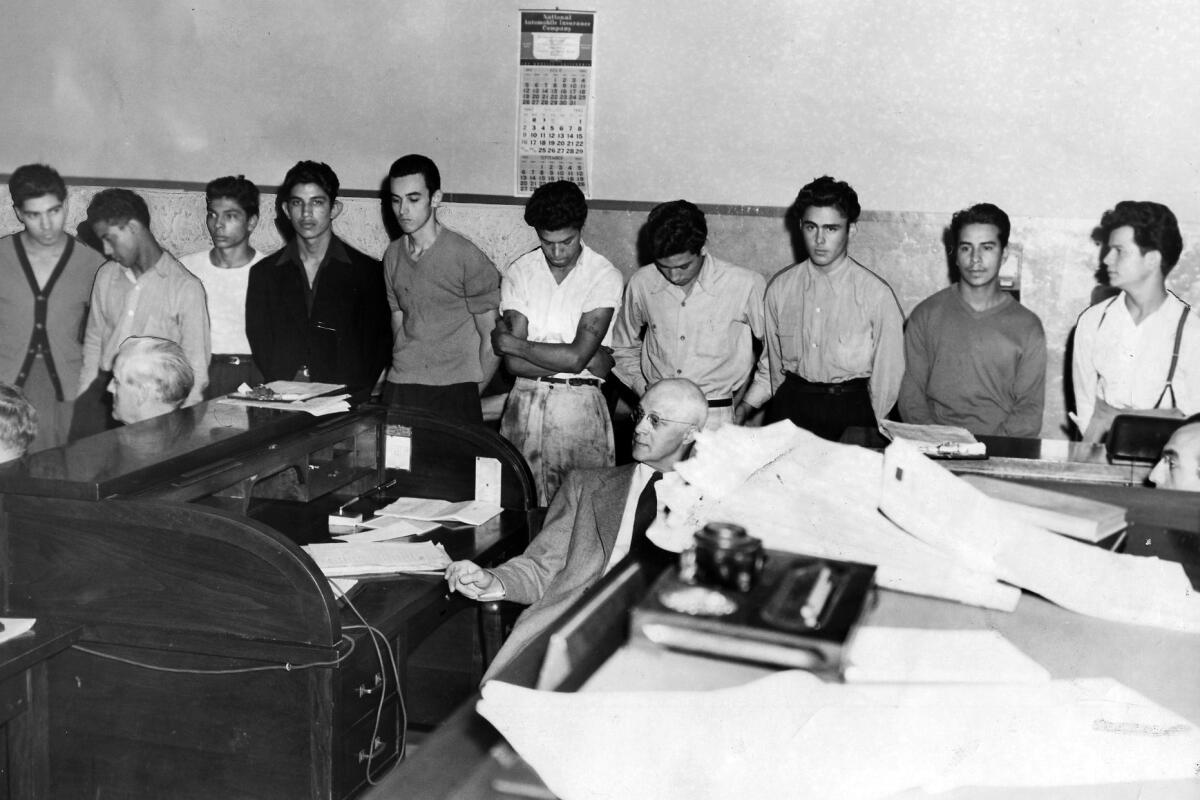

The Times reports that of the more than 600 men and boys arrested, 29 remain in custody.

Three women are also held at the county jail: Dora Barrios, Frances Silva and Lorena Encinas. The women say they were at the Williams Ranch party but deny belonging to the 38th Street gang, and refuse to give any information about what happened the night Diaz was attacked.

Sheriff Eugene Biscailuz assignes “a special squad of deputies, many of them of Mexican descent” to investigate Diaz’s killing.

The Times begins writing about zoot suits, calling it the attire of “organized groups of youths, mostly Mexican, engaged in the rival gang fights.”

“The boys and even their girl friends wear a distinctive dress so that they can identify each other easily during a brawl,” says the front-page story headlined “Ranch Killing Inquiry Opens. Witnesses Questioned in Fatal Party Attack; Hoodlum Roundup Pushed.”

Above, a group of men and boys who were arrested. Manuel Delgado and Jack Melendez, third and fourth from left, would soon go on trial.

Three women are also held at the county jail: Dora Barrios, Frances Silva and Lorena Encinas. The women say they were at the Williams Ranch party but deny belonging to the 38th Street gang, and refuse to give any information about what happened the night Diaz was attacked.

Sheriff Eugene Biscailuz assignes “a special squad of deputies, many of them of Mexican descent” to investigate Diaz’s killing.

The Times begins writing about zoot suits, calling it the attire of “organized groups of youths, mostly Mexican, engaged in the rival gang fights.”

“The boys and even their girl friends wear a distinctive dress so that they can identify each other easily during a brawl,” says the front-page story headlined “Ranch Killing Inquiry Opens. Witnesses Questioned in Fatal Party Attack; Hoodlum Roundup Pushed.”

Above, a group of men and boys who were arrested. Manuel Delgado and Jack Melendez, third and fourth from left, would soon go on trial.

Show more Show less

Route Details

Oct. 13, 1942: Los Angeles County Courthouse

Los Angeles L.A. History

(Los Angeles Times)

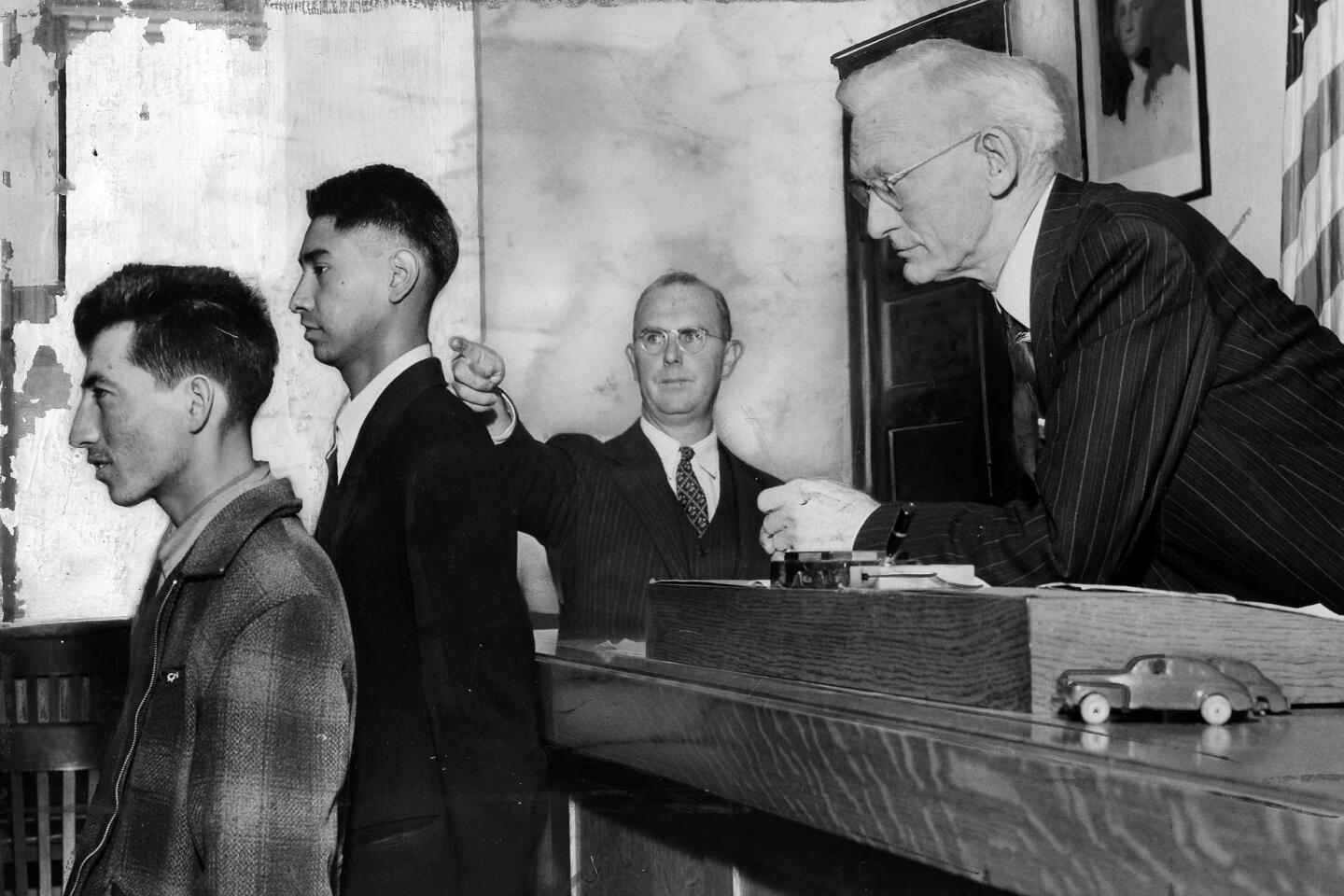

What would become known at the Sleepy Lagoon Murder Trial begins.

Of the hundreds of men and boys police arrested, a grand jury indicts 22 on charges of conspiracy to commit murder and two charges of assault with a deadly weapon.

Seventeen men and boys are tried en masse, with prosecutors emphasizing racial stereotypes to explain Diaz’s killing.

Five others — Edward Grandpré, Ruben Peña, Daniel Verdugo, Joe Carpio and Richard Gastelum — request and are granted separate trials.

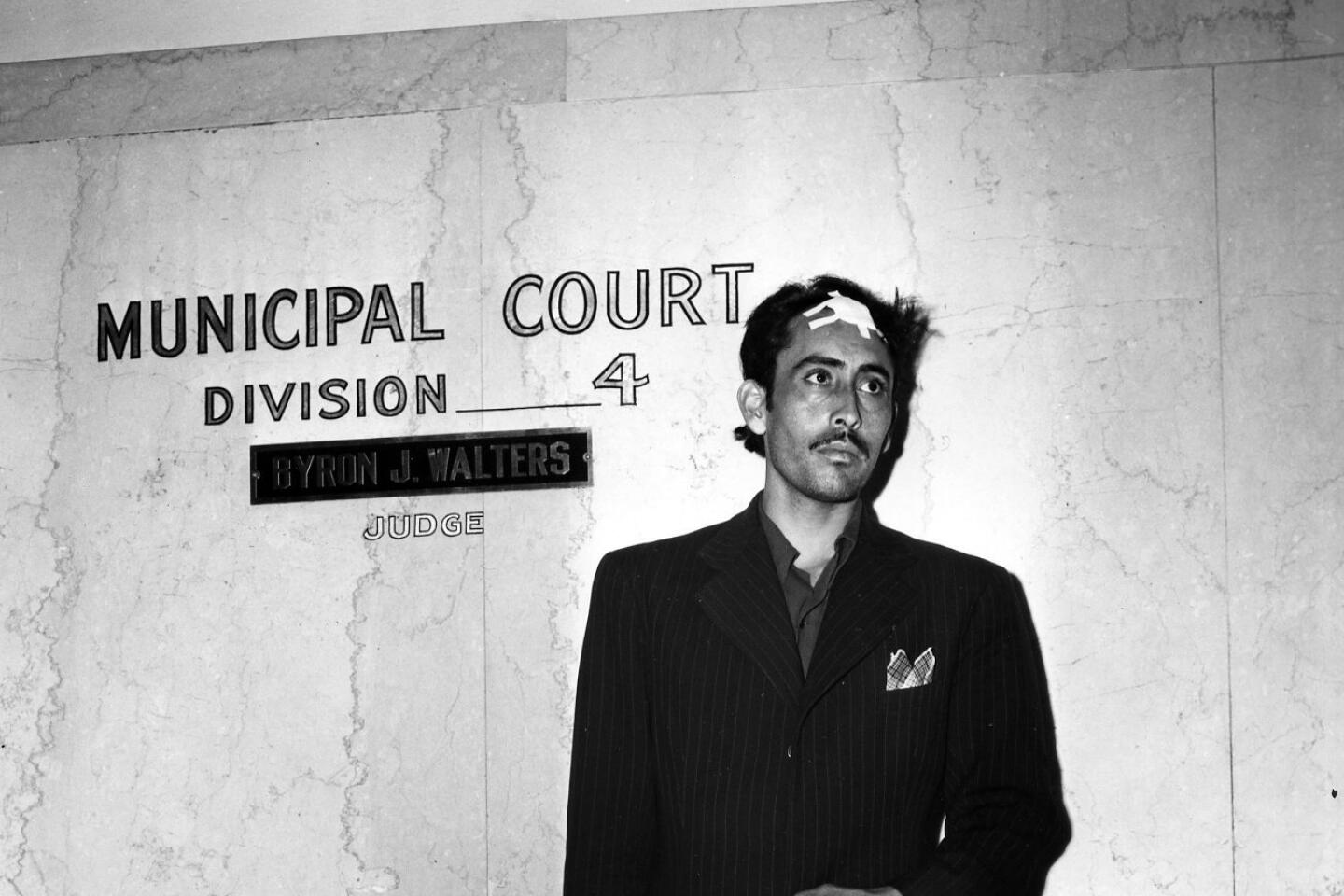

Above, Leyvas with some other defendants in the background.

In his obituary in 1958, The Times wrote that Fricke had “sentenced more killers to death than any other jurist in the history of California jurisprudence.” He also was known for sending minors to state prison rather than forestry camp.

Fricke refuses to let the defendants change their clothes, comb or cut their hair or sit next to their attorneys during the trial. The media begin writing about gang identifiers, including a popular hairstyle among Mexican youths known as the “ducktail haircut.”

Fricke also allows the jury to read newspapers everyday during the trial. The Times begins to call the defendants the “Zoot Suit Slayers.”

Sheriff’s Capt. Edward Duran Ayres, who prepared a report for the grand jury, wrote that Mexicans had a “desire to use a knife or some lethal weapon. In other words ... desire is to kill, or at least, let blood.” He attributed this to the sacrificial practices of the Aztecs.

He also insinuated a link between Mexico and wartime foe Japan, saying the defendants’ ancestors “crossed the ice bridge between North America and Asia.” People from the two countries were “cousins,” he wrote.

“The Indian, from Alaska to Patagonia, is evidently Oriental in background — at least he shows many of the Oriental characteristics, especially so in his utter disregard for the value of life,” Ayres wrote.

Delgadillo Coronado identified three of the 17 defendants in her testimony as part of the group that crashed their party: Leyvas, Melendez, and Parra.

Manfredi also identified Leyvas and Parra as party crashers, along with Delgado, but did not identify any of the defendants as the person who stabbed him.

Multiple witnesses said they gave false statements during the grand jury inquiry because of police intimidation.

Of the hundreds of men and boys police arrested, a grand jury indicts 22 on charges of conspiracy to commit murder and two charges of assault with a deadly weapon.

Seventeen men and boys are tried en masse, with prosecutors emphasizing racial stereotypes to explain Diaz’s killing.

The accused

The 17 tried together were Henry Leyvas, Ysmael “Smiles” Parra, Jose “Chepe” Ruíz, Manuel “Manny” Delgado, Manuel “Manny” Reyes Salazar, Victor “Bobby Levine” Rodman Thompson, Henry “Hank” Joseph Ynostroza, Andrew Acosta, Eugene Carpio, Benny Alvarez, Gustavo “Gus” Zamora, Victor Segobia, Joseph Valenzuela, Jack Melendez, Robert “Bobby” Telles, John Matuz and Angel Padilla.Five others — Edward Grandpré, Ruben Peña, Daniel Verdugo, Joe Carpio and Richard Gastelum — request and are granted separate trials.

Above, Leyvas with some other defendants in the background.

The judge

The all-white jury hears the case under the supervision of Judge Charles W. Fricke.In his obituary in 1958, The Times wrote that Fricke had “sentenced more killers to death than any other jurist in the history of California jurisprudence.” He also was known for sending minors to state prison rather than forestry camp.

Fricke refuses to let the defendants change their clothes, comb or cut their hair or sit next to their attorneys during the trial. The media begin writing about gang identifiers, including a popular hairstyle among Mexican youths known as the “ducktail haircut.”

Fricke also allows the jury to read newspapers everyday during the trial. The Times begins to call the defendants the “Zoot Suit Slayers.”

The witnesses

Over the 13-week trial, the prosecution presents multiple “expert” witnesses who give racist testimony on the Mexican community and its culture.Sheriff’s Capt. Edward Duran Ayres, who prepared a report for the grand jury, wrote that Mexicans had a “desire to use a knife or some lethal weapon. In other words ... desire is to kill, or at least, let blood.” He attributed this to the sacrificial practices of the Aztecs.

He also insinuated a link between Mexico and wartime foe Japan, saying the defendants’ ancestors “crossed the ice bridge between North America and Asia.” People from the two countries were “cousins,” he wrote.

“The Indian, from Alaska to Patagonia, is evidently Oriental in background — at least he shows many of the Oriental characteristics, especially so in his utter disregard for the value of life,” Ayres wrote.

Delgadillo Coronado identified three of the 17 defendants in her testimony as part of the group that crashed their party: Leyvas, Melendez, and Parra.

Manfredi also identified Leyvas and Parra as party crashers, along with Delgado, but did not identify any of the defendants as the person who stabbed him.

Multiple witnesses said they gave false statements during the grand jury inquiry because of police intimidation.

Show more Show less

Route Details

Dec. 5, 1942: Ventura School for Girls

Ventura L.A. History

(Ray Graham / Los Angeles Times)

Three women who refused testify at the trial about what happened at the party at Williams Ranch are sent to the Ventura School for Girls for a year without a trial.

The reform school was a correctional facility for girls who were seen as delinquent and sexually promiscuous.

The day before Frances Silva arrives at the facility, she swallows a sewing needle in protest to her sentencing. She survives and serves her sentence.

Above, from left, Dora Barrios, Silva and Lorena Encinas.

The reform school was a correctional facility for girls who were seen as delinquent and sexually promiscuous.

The day before Frances Silva arrives at the facility, she swallows a sewing needle in protest to her sentencing. She survives and serves her sentence.

Above, from left, Dora Barrios, Silva and Lorena Encinas.

Show more Show less

Route Details

Jan. 12, 1943: Los Angeles County Courthouse

Los Angeles L.A. History

(Los Angeles Times)

After several days of deliberation, without any physical evidence linking them to the crime, the jury finds all 17 defendants guilty.

Leyvas, Telles and Ruiz are convicted of first-degree murder and sent to San Quentin Penitentiary for life.

Zamora, Ynostroza, Thompson, Parra, Padilla, Matuz, Delgado, Melendez and Reyes are found guilty of second-degree murder and sentenced to state prison in Chino.

The remaining defendants receive sentences ranging from six months to a year at L.A. County jail on assault charges.

Above, Deputy Sheriff William Cordes clears the courtroom of a weeping woman after the verdict.

The five who obtained separate trials were later found not guilty.

Leyvas, Telles and Ruiz are convicted of first-degree murder and sent to San Quentin Penitentiary for life.

Zamora, Ynostroza, Thompson, Parra, Padilla, Matuz, Delgado, Melendez and Reyes are found guilty of second-degree murder and sentenced to state prison in Chino.

The remaining defendants receive sentences ranging from six months to a year at L.A. County jail on assault charges.

Above, Deputy Sheriff William Cordes clears the courtroom of a weeping woman after the verdict.

The five who obtained separate trials were later found not guilty.

Show more Show less

Route Details

May 31, 1943: North Main Street

Los Angeles L.A. History

Off-duty sailors from the naval base in Chavez Ravine get into an altercation with young Mexican men wearing zoot suits in downtown L.A.

Sailor Joe Dacy Coleman leaves the altercation with a broken jaw. Upon returning to the base, other servicemen begin plotting a return to the area the next night.

Route Details

June 2, 1943: Times Mirror Square

Los Angeles L.A. History

(Los Angeles Times)

The Times publishes its fourth story in a series about “delinquent crime” that focuses on Mexican Americans who wore zoot suits.

The story, headlined with “Youth Gangs Leading Cause of Delinquencies,” begins with: “Fresh in the memory of Los Angeles is last year’s surge of gang violence that made the ‘zoot suit’ a badge of delinquency.”

The story takes aim at Mexican parents and households, claiming that children of foreign-born parents were more likely to pose a “delinquency problem,” and non-English-speaking households “cling to past culture” making it a “serious factor of delinquency. Parents in such a home lack control over their offspring.”

In the same issue, the paper publishes a story about the search for suspects involved in a “zoot suit orgy” at Elysian Park that involved “zoot-suited Negroes and Mexicans.”

Show more Show less

Route Details

June 3, 1943: North Main Street

Los Angeles L.A. History

(Associated Press)

A day after the Times stories focusing on zoot suits, servicemen and off-duty policemen who volunteered to form a “vengeance squad” after Coleman received a broken jaw, ambush Mexican Angelenos.

Detective Sgt. E.A. Tetrick tells the press “a group of officers agreed to stay overtime and ‘clean out’ the district of North Main street.”

Tetrick also says, “The squad will continue in operation until the condition is entirely cleaned up.”

Above, Deputy Sheriff Bartley Brown of East Los Angeles inspects the haircut of Alex “Largo” Rodriguez, who is wearing an $85 zoot suit.

Detective Sgt. E.A. Tetrick tells the press “a group of officers agreed to stay overtime and ‘clean out’ the district of North Main street.”

Tetrick also says, “The squad will continue in operation until the condition is entirely cleaned up.”

Above, Deputy Sheriff Bartley Brown of East Los Angeles inspects the haircut of Alex “Largo” Rodriguez, who is wearing an $85 zoot suit.

Show more Show less

Route Details

June 4, 1943: Belvedere Gardens

East Los Angeles L.A. History

A reported 200 off-duty Navy officers turn their attention from North Main Street to Belvedere Gardens and Bunker Hill. With the help of 20 taxicabs, the servicemen hunt anyone in a zoot suit.

The Associated Press, reporting from the scene, writes that the servicemen applied “fists and rope ends to zoot-suited youths.”

“We’re enlisting the aid of the Marine’s for tonight’s expedition,” a Naval petty officer tells the United Press. “Pretty soon there’ll be no more of these pachucos.”

AP reports “four of the weirdly-clad youths” were treated at hospitals, stating they were attacked by sailors.

Violence against zoot suiters is also reported in Bunker Hill on the same night.

The Associated Press, reporting from the scene, writes that the servicemen applied “fists and rope ends to zoot-suited youths.”

“We’re enlisting the aid of the Marine’s for tonight’s expedition,” a Naval petty officer tells the United Press. “Pretty soon there’ll be no more of these pachucos.”

AP reports “four of the weirdly-clad youths” were treated at hospitals, stating they were attacked by sailors.

Violence against zoot suiters is also reported in Bunker Hill on the same night.

Show more Show less

Route Details

June 5-6, 1943: Various L.A. locations

Los Angeles L.A. History

(Los Angeles Times)

The off-duty sailors maintain their nightly “patrol” of L.A. as violence spreads from downtown to East L.A. and other pockets of the city.

The racist mobs use the place where they believed Coleman was assaulted to congregate and fan out throughout the city, either by foot or taxi rides offered up free of charge.

Police officers arrest 61 Mexican men and boys on the nights of June 5 and 6. The Long Beach Sun reports, “Many of the zoot-suiters are between 13 and 17 years old.”

Justice of the Peace Myer Marion in Belvedere Justice Court gave fines up to $250 or 90 days in jail to Mexican boys who were arrested on charges of loitering, vagrancy and assault with deadly weapons.

The sailors stripped the men and boys of their zoot suits and beat them in the streets.

In movie theaters throughout the city, the servicemen had operators turn on the house lights in the middle of shows so they could hunt down anyone in a zoot suits.

Other reports of violence from the week include that of a boy who was “forcibly deprived of his trousers, and thrown into a passing garbage truck.”

The Times applauds the sailors. A front-page story from June 7 reads: “Those gamin dandies, zoot suiters, having learned a great moral lesson from servicemen, mostly sailors, who took over their instruction three days ago, are staying home nights.”

Above, Mexican men and boys who were arrested during the unrest.

The racist mobs use the place where they believed Coleman was assaulted to congregate and fan out throughout the city, either by foot or taxi rides offered up free of charge.

Police officers arrest 61 Mexican men and boys on the nights of June 5 and 6. The Long Beach Sun reports, “Many of the zoot-suiters are between 13 and 17 years old.”

Justice of the Peace Myer Marion in Belvedere Justice Court gave fines up to $250 or 90 days in jail to Mexican boys who were arrested on charges of loitering, vagrancy and assault with deadly weapons.

The sailors stripped the men and boys of their zoot suits and beat them in the streets.

In movie theaters throughout the city, the servicemen had operators turn on the house lights in the middle of shows so they could hunt down anyone in a zoot suits.

Other reports of violence from the week include that of a boy who was “forcibly deprived of his trousers, and thrown into a passing garbage truck.”

The Times applauds the sailors. A front-page story from June 7 reads: “Those gamin dandies, zoot suiters, having learned a great moral lesson from servicemen, mostly sailors, who took over their instruction three days ago, are staying home nights.”

Above, Mexican men and boys who were arrested during the unrest.

Show more Show less

Route Details

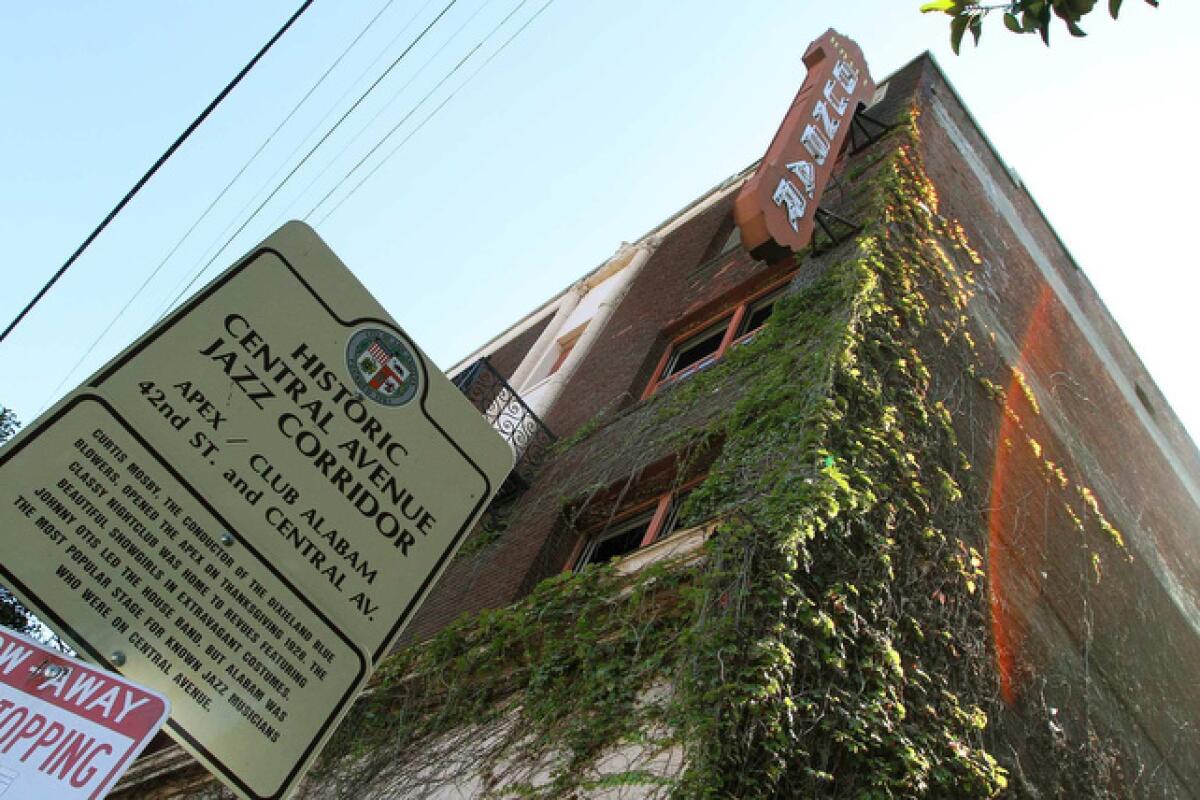

June 6, 1943: Central Avenue

Historic South-Central L.A. History

(Los Angeles Times)

The violent mob grows, adding Marines and white civilians, and so did the number of targets. The servicemen and other move from Mexican American communities to the Black neighborhood of South Central Avenue, the jazz hub of L.A.

The Los Angeles Evening Citizen News report, “The raiding groups had grown to the proportions of any army, and the original reprisal motives seemed to have disappeared as Negroes and Mexicans were attacked, without discrimination and regardless of garb.”

Various reports of violence against Filipinos at the time of the riots have emerged throughout the years.

The Los Angeles Evening Citizen News report, “The raiding groups had grown to the proportions of any army, and the original reprisal motives seemed to have disappeared as Negroes and Mexicans were attacked, without discrimination and regardless of garb.”

Various reports of violence against Filipinos at the time of the riots have emerged throughout the years.

Show more Show less

Route Details

June 7, 1943: City Hall

Downtown L.A. L.A. History

(Los Angeles Times)

Several hundred servicemen and civilians patrolling downtown gather at City Hall after word spreads along Main Street that a group of Black and Mexican men were on the second floor.

A detective lieutenant eventually persuaded the crowd to disperse after explaining that the men on the second floor were janitors employed by the city.

Above, a mob surrounds a trolley on Main Street in downtown L.A. The mob pulled anyone in a zoot suit off the trolley.

A detective lieutenant eventually persuaded the crowd to disperse after explaining that the men on the second floor were janitors employed by the city.

Above, a mob surrounds a trolley on Main Street in downtown L.A. The mob pulled anyone in a zoot suit off the trolley.

Show more Show less

Route Details

June 7, 1943: Fifth and Main Street

Downtown L.A. L.A. History

(Harold P. Matosian / Associated Press)

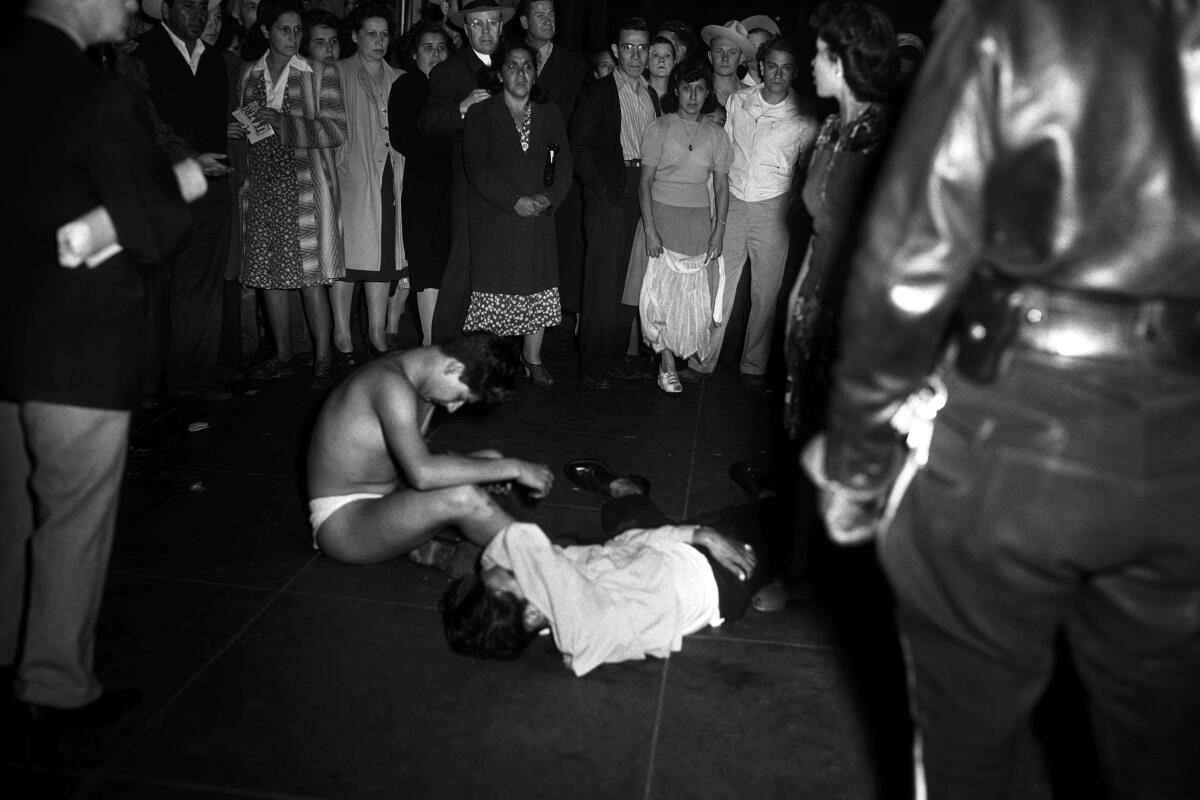

Otis Peterson, a 25-year-old Black Angeleno, becomes the first to report to police that the servicemen robbed him of more than his suit.

Peterson said he was chased by 40 sailors and Marines, and while attempting to hide in a theater, asked a police officer for protection from the mob. The cop refused and told him to “get that zoot suit off,” Peterson said.

The mob eventually caught up with Peterson, stripped him of his zoot suit and took the $42 he had on him. Stripping men and boys of their clothing was applauded on The Times’ editorial pages.

Columnist Ed Ainsworth wrote, “Rarely has a style trend changed so rapidly, a zoot suiter starts down the street and by the time he gets half a block he is a walking advertisement for the Garden of Eden, with all gifts of fig leaves thankfully received. … P.S. for the sailors, soldiers and marines: Boys, we admire your tastes in styles!”

Above, two young men who were stripped of their clothing during the riots.

Peterson said he was chased by 40 sailors and Marines, and while attempting to hide in a theater, asked a police officer for protection from the mob. The cop refused and told him to “get that zoot suit off,” Peterson said.

The mob eventually caught up with Peterson, stripped him of his zoot suit and took the $42 he had on him. Stripping men and boys of their clothing was applauded on The Times’ editorial pages.

Columnist Ed Ainsworth wrote, “Rarely has a style trend changed so rapidly, a zoot suiter starts down the street and by the time he gets half a block he is a walking advertisement for the Garden of Eden, with all gifts of fig leaves thankfully received. … P.S. for the sailors, soldiers and marines: Boys, we admire your tastes in styles!”

Above, two young men who were stripped of their clothing during the riots.

Show more Show less

Route Details

June 7, 1943: Central and 12th

Downtown L.A. L.A. History

Radio stations broadcast the locations of where the next round of violence was expected to occur, and taxi drivers offered free rides to any white person heading to the areas.

In 2006, RJ Smith, author of “The Great Black Way: L.A. in the 1940s and the Last African American Renaissance,” would describe June 7 as a pivotal moment in the riots.

On that night, “word spread that white sailors were expanding the battle and planned to mount that night’s assault on Central Avenue, in the heart of black Los Angeles,” he wrote. This time, however, the Black and Mexican American communities fought back.

Loren Miller, a journalist for the Los Angeles Sentinel in 1943, said in an interview that he had warned Mayor Fletcher Bowron, not for the safety of the Black residents of the neighborhood, but for the safety of the white mob that wasn’t aware of what was waiting for them.

“We were going to raise hell and see that anybody that came over in the Negro community looking around for any trouble was going to find plenty of trouble,” Miller said. “[I] told them that if anybody came up to 12th and Central, somebody was going to get killed, and I didn’t think it was going to be Negroes.”

The neighborhood residents didn’t fight alone. Smith reported that “at least 500 Latinos came into the neighborhood — including members of the Jug Town, Adams, Clanton, Watts, 38th Street and Jardine gangs — to fight on behalf of the Black community against a common enemy.”

Years after the night of the battle of 12th Street, Almena Lomax, editor and publisher of the Los Angeles Tribune, described what she reported that night.

“The little Mexican girls were ferocious,” she said.

Rudy Leyvas, a participant of the defense of the neighborhood, described the group’s strategy to The Times years later.

“We started hiding in alleys,” he said. “Then we sent about 20 guys right out into the middle of the street as decoys. Then they came up in U.S. Navy trucks. There were many civilians too. There was at least as many of them as us. They started coming after the decoys, then we came out. They were surprised. It was the first time anybody was organized to fight back.”

In 2006, RJ Smith, author of “The Great Black Way: L.A. in the 1940s and the Last African American Renaissance,” would describe June 7 as a pivotal moment in the riots.

On that night, “word spread that white sailors were expanding the battle and planned to mount that night’s assault on Central Avenue, in the heart of black Los Angeles,” he wrote. This time, however, the Black and Mexican American communities fought back.

Loren Miller, a journalist for the Los Angeles Sentinel in 1943, said in an interview that he had warned Mayor Fletcher Bowron, not for the safety of the Black residents of the neighborhood, but for the safety of the white mob that wasn’t aware of what was waiting for them.

“We were going to raise hell and see that anybody that came over in the Negro community looking around for any trouble was going to find plenty of trouble,” Miller said. “[I] told them that if anybody came up to 12th and Central, somebody was going to get killed, and I didn’t think it was going to be Negroes.”

The neighborhood residents didn’t fight alone. Smith reported that “at least 500 Latinos came into the neighborhood — including members of the Jug Town, Adams, Clanton, Watts, 38th Street and Jardine gangs — to fight on behalf of the Black community against a common enemy.”

Years after the night of the battle of 12th Street, Almena Lomax, editor and publisher of the Los Angeles Tribune, described what she reported that night.

“The little Mexican girls were ferocious,” she said.

Rudy Leyvas, a participant of the defense of the neighborhood, described the group’s strategy to The Times years later.

“We started hiding in alleys,” he said. “Then we sent about 20 guys right out into the middle of the street as decoys. Then they came up in U.S. Navy trucks. There were many civilians too. There was at least as many of them as us. They started coming after the decoys, then we came out. They were surprised. It was the first time anybody was organized to fight back.”

Show more Show less

Route Details

June 8, 1943: North Main Street

Los Angeles L.A. History

(Associated Press)

The day after 50 zoot suiters were reported beaten in another night of violence, military command staff finally intervene. With charred suits still smoldering in the streets, servicemen are restricted from the areas of downtown and East L.A.

The Times reports sporadic violence in the region on the night of June 8, particularly in Long Beach, where sailor W.W. West is arrested on charges of inciting a riot. West and others beat Stephen Amador, whose brother was serving in the military. West is released the same night.

Overall, the night remains mostly quiet, and June 8 is considered the end of what would later be known as the Zoot Suit Riots.

There were no deaths reported that were linked to the riots. An estimated 94 civilians and 18 servicemen were seriously injured.

Over 500 Mexicans were arrested and charged with a crime during the riots. While some servicemen were arrested and held in the early days of the unrest, they were released the same night that they were arrested, and never charged with a crime.

Above, young Angelenos note the end of hostilities by cruising downtown streets, waving American and white flags. The Associated Press reports that the people photographed were told by police that they would be protected as American citizens but would not be allowed to congregate in gangs.

The Times reports sporadic violence in the region on the night of June 8, particularly in Long Beach, where sailor W.W. West is arrested on charges of inciting a riot. West and others beat Stephen Amador, whose brother was serving in the military. West is released the same night.

Overall, the night remains mostly quiet, and June 8 is considered the end of what would later be known as the Zoot Suit Riots.

There were no deaths reported that were linked to the riots. An estimated 94 civilians and 18 servicemen were seriously injured.

Over 500 Mexicans were arrested and charged with a crime during the riots. While some servicemen were arrested and held in the early days of the unrest, they were released the same night that they were arrested, and never charged with a crime.

Above, young Angelenos note the end of hostilities by cruising downtown streets, waving American and white flags. The Associated Press reports that the people photographed were told by police that they would be protected as American citizens but would not be allowed to congregate in gangs.

Show more Show less

Route Details

June 9, 1943: Consulate General of Mexico in Los Angeles

Westside L.A. History

(Associated Press)

California Gov. Earl Warren orders state Atty. Gen. Robert Kenny and a five-person citizens committee to launch an investigation into the riots after the Mexican Embassy threatens a formal protest with the State Department.

An embassy official says many of those attacked were “innocent Mexican bystanders.”

The members of the committee are Bishop Joseph McGucken, pastor Willsie Martin, Director of the California Youth Authority Carl Horton, attorney and civil rights activist Walter Gordon and actor Leo Carrillo.

Gordon, a Black man, and Carrillo are the only nonwhite members of the committee.

The day after the committee is formed, Mexican Ambassador Francisco Castillo Najera says he would not make a protest because it appeared the situation had “greatly improved.”

Above, Castillo Najera, left, at the White House with Mexican Minister of National Economy Francisco Gaxiola.

An embassy official says many of those attacked were “innocent Mexican bystanders.”

The members of the committee are Bishop Joseph McGucken, pastor Willsie Martin, Director of the California Youth Authority Carl Horton, attorney and civil rights activist Walter Gordon and actor Leo Carrillo.

Gordon, a Black man, and Carrillo are the only nonwhite members of the committee.

The day after the committee is formed, Mexican Ambassador Francisco Castillo Najera says he would not make a protest because it appeared the situation had “greatly improved.”

Above, Castillo Najera, left, at the White House with Mexican Minister of National Economy Francisco Gaxiola.

Show more Show less

Route Details

June 10, 1943: City Hall

Downtown L.A. L.A. History

(Los Angeles Times)

The Times, in an article headlined “Ban on Freak Suits Studied by Councilman,” reports that the L.A. City Council began seriously discussing a ban on zoot suits, and it would be a jail offense for anyone caught in the suit.

The council approves the resolution, but the ordinance never goes into effect. Instead, the council urges the War Production Board to take even further steps to curb the production of zoot suits.

The council approves the resolution, but the ordinance never goes into effect. Instead, the council urges the War Production Board to take even further steps to curb the production of zoot suits.

Show more Show less

Route Details

June 10, 1943: Watts

Watts L.A. History

(Anthony Potter Collection / Getty Images)

With almost all of L.A. off limits to military servicemen, sailors continue to look for areas to roam and hunt zoot suiters. The sailors believed Watts was not part of the city, and that leads to a daytime showdown between sailors and young zoot suiters.

When the sailors return that night, they arrive to mostly empty streets, with police telling them to leave. The Associated Press reported days earlier that men in U.S. uniforms invaded private homes in Watts. By now the riots are considered over.

When the sailors return that night, they arrive to mostly empty streets, with police telling them to leave. The Associated Press reported days earlier that men in U.S. uniforms invaded private homes in Watts. By now the riots are considered over.

Show more Show less

Route Details

June 13, 1943: Downtown Los Angeles

Los Angeles L.A. History

(Associated Press)

The citizens committee presents its report to Gov. Warren, above, and calls for punishing anyone responsible for the violence that occurred “regardless of what clothes they wear, whether they be zoot suits, police, Army or Navy uniforms.”

The report also states, “It is a mistake in fact and aggravating practice to link the phrase ‘zoot suit’ with the report of crime.”

As for the cause of the violence, the answer was simple for the committee: “In undertaking to deal with the cause of these outbreaks, the existence of race prejudice cannot be ignored.”

The committee finds it to be “significant” that most of the victims of violence during the riots were “either persons of Mexican descent or Negroes.”

The report also states, “It is a mistake in fact and aggravating practice to link the phrase ‘zoot suit’ with the report of crime.”

As for the cause of the violence, the answer was simple for the committee: “In undertaking to deal with the cause of these outbreaks, the existence of race prejudice cannot be ignored.”

The committee finds it to be “significant” that most of the victims of violence during the riots were “either persons of Mexican descent or Negroes.”

Show more Show less

Route Details

June 16, 1943: Times Mirror Square

Los Angeles L.A. History

(Associated Press)

First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt at a news conference expresses concerns about what had happened in L.A.

“For a long time I’ve worried about the attitude toward Mexicans in California and the states along the border,” she says. Roosevelt says the riots could be traced to long-standing discrimination against Mexicans.

The Times disagreed with the first lady.

Two days later, the paper published an editorial titled “Mrs. Roosevelt Blindly Stirs Race Discord.”

The editorial said Roosevelt’s comments demonstrated “ignorance” and reflected “an amazing similarity to the Communist party line propaganda.

“Mrs. Roosevelt with characteristic lack of understanding has added nasty fuel to a propaganda fire … in twisting the zoot trouble into something it isn’t, a race-hatred problem.”

“For a long time I’ve worried about the attitude toward Mexicans in California and the states along the border,” she says. Roosevelt says the riots could be traced to long-standing discrimination against Mexicans.

The Times disagreed with the first lady.

Two days later, the paper published an editorial titled “Mrs. Roosevelt Blindly Stirs Race Discord.”

The editorial said Roosevelt’s comments demonstrated “ignorance” and reflected “an amazing similarity to the Communist party line propaganda.

“Mrs. Roosevelt with characteristic lack of understanding has added nasty fuel to a propaganda fire … in twisting the zoot trouble into something it isn’t, a race-hatred problem.”

Show more Show less

Route Details

Oct. 20, 1943: Sleepy Lagoon Defense Committee

Downtown L.A. L.A. History

(Los Angeles Times)

The reverberations of the Sleepy Lagoon Murder Trial, which fueled anti-Mexican sentiment before the riots, are still felt. On this day, supporters of the 17 men and boys imprisoned for murdering Jose Diaz file an appeal to overturn their convictions.

The effort is led by the Sleepy Lagoon Defense Committee, originally called the Citizens’ Committee for the Defense of Mexican American Youth. It was formed during the 1942 trial by labor organizer LaRue McCormick.

Three join the committee and become key to its efforts: lawyer Ben Margolis, activist Alice McGrath and author and lawyer Carey McWilliams.

Members of the Mexican government showed their support for the committee in the press.

Actor Anthony Quinn, whose real name was Manuel Antonio Rodolfo Quinn Oaxaca, recruited other Hollywood actors, such as Orson Welles and Rita Hayworth, whose real name was Margarita Carmen Cansino, to help support the cause. Welles had his letter to the parole board published in the California Eagle.

A jazz concert headlined by the Nat King Cole Trio was held at the Philharmonic Auditorium with the proceeds going to the defense committee.

The committee said the defendants were convicted “on the basis of prejudice, evidence erroneously admitted and considered, misconduct of the court and numerous errors of law.”

Margolis also targeted the eyewitness testimony of those who attended the Williams Ranch party, saying there was no evidence that any of the defendants were near the area on the night Diaz was killed.

The committee published a 48-page book by Joe Endore, in which Endore claimed Diaz died from a car accident, not a murder, despite a coroner’s investigation that revealed Diaz was stabbed twice.

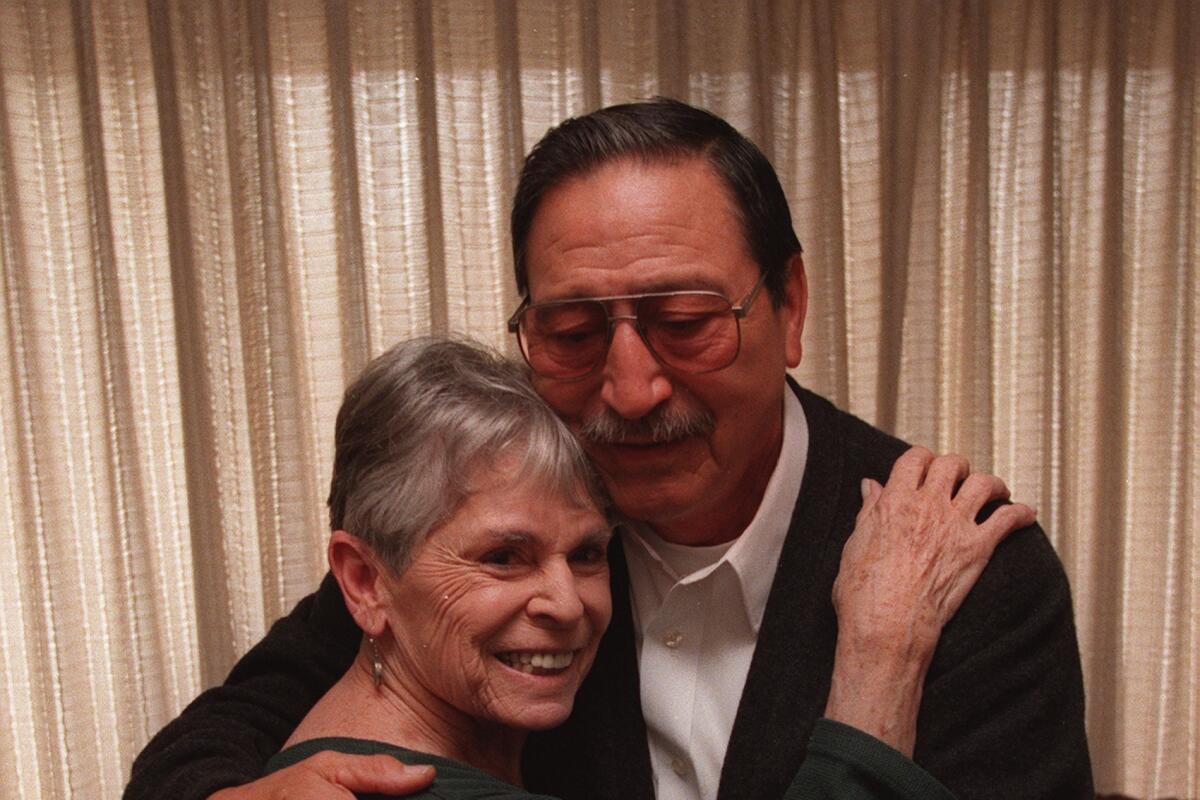

Above, McGrath and Sleepy Lagoon defendant Manuel Reyes in 1997.

The effort is led by the Sleepy Lagoon Defense Committee, originally called the Citizens’ Committee for the Defense of Mexican American Youth. It was formed during the 1942 trial by labor organizer LaRue McCormick.

Three join the committee and become key to its efforts: lawyer Ben Margolis, activist Alice McGrath and author and lawyer Carey McWilliams.

Members of the Mexican government showed their support for the committee in the press.

Actor Anthony Quinn, whose real name was Manuel Antonio Rodolfo Quinn Oaxaca, recruited other Hollywood actors, such as Orson Welles and Rita Hayworth, whose real name was Margarita Carmen Cansino, to help support the cause. Welles had his letter to the parole board published in the California Eagle.

A jazz concert headlined by the Nat King Cole Trio was held at the Philharmonic Auditorium with the proceeds going to the defense committee.

The committee said the defendants were convicted “on the basis of prejudice, evidence erroneously admitted and considered, misconduct of the court and numerous errors of law.”

Margolis also targeted the eyewitness testimony of those who attended the Williams Ranch party, saying there was no evidence that any of the defendants were near the area on the night Diaz was killed.

The committee published a 48-page book by Joe Endore, in which Endore claimed Diaz died from a car accident, not a murder, despite a coroner’s investigation that revealed Diaz was stabbed twice.

Above, McGrath and Sleepy Lagoon defendant Manuel Reyes in 1997.

Show more Show less

Route Details

Oct. 2, 1944: California 2nd District Court of Appeal

Downtown L.A. L.A. History

(Los Angeles Times)

An appeals court overturns the convictions of the Sleepy Lagoon defendants. The court had heard arguments from defense committee attorneys in May.

The decision says the “evidence presented at the trial was insufficient to establish guilt of the defendants,” and criticizes the conduct of Judge Fricke.

Above, a crowd gathered on Oct. 24 at the Hall of Justice in downtown Los Angeles greets the wrongly convicted youths after their release.

The decision says the “evidence presented at the trial was insufficient to establish guilt of the defendants,” and criticizes the conduct of Judge Fricke.

Above, a crowd gathered on Oct. 24 at the Hall of Justice in downtown Los Angeles greets the wrongly convicted youths after their release.

Show more Show less

Route Details

2023: Calvary Cemetery and Mortuary

East Los Angeles L.A. History

(Mel Melcon/Los Angeles Times)

Many of the symbols and sites related to the Zoot Suit Riots are gone, including the swimming hole that was dubbed Sleepy Lagoon.

But one can find the grave of Jose Diaz.

Though his death would lead to the show trial of 17 men and boys and later to the riots, he’s somehow become a largely forgotten character in the dramas that played out in wartime L.A. In 2022, on the 80th anniversary of Diaz’s death, columnist Gustavo Arellano wrote that a book by Eduardo Obregon Pagan — “Murder at the Sleepy Lagoon: Zoot Suits, Race, & Riot in Wartime L.A.” — “remains the only major work that spent any time on who Diaz was.”

Pagan’s book, and his contribution to the PBS series “American Experience,” described Diaz as a quiet man who helped his family with farm work. In L.A., he discovered jazz culture and began dressing like some of his favorite musicians. He had joined the Army and was awaiting deployment.

His killing remains unsolved.

But one can find the grave of Jose Diaz.

Though his death would lead to the show trial of 17 men and boys and later to the riots, he’s somehow become a largely forgotten character in the dramas that played out in wartime L.A. In 2022, on the 80th anniversary of Diaz’s death, columnist Gustavo Arellano wrote that a book by Eduardo Obregon Pagan — “Murder at the Sleepy Lagoon: Zoot Suits, Race, & Riot in Wartime L.A.” — “remains the only major work that spent any time on who Diaz was.”

Pagan’s book, and his contribution to the PBS series “American Experience,” described Diaz as a quiet man who helped his family with farm work. In L.A., he discovered jazz culture and began dressing like some of his favorite musicians. He had joined the Army and was awaiting deployment.

His killing remains unsolved.

Show more Show less

Route Details

No matching entries.

Please reset filters to see all entries.

No matching entries.

Please reset filters to see all entries.

Top