Why is a public hospital in L.A. restraining psychiatric patients at high rates?

- Share via

Good morning. It’s Thursday, Oct. 19. I’m Emily Alpert Reyes, a public health reporter for the Los Angeles Times. Here’s what you need to know to start your day.

- Inside L.A. General Medical Center’s handling of psychiatric patients

- What do Hamas and Israel see as the endgame?

- Ten Halloween events and attractions to rattle and shake your bones

- And here’s today’s e-newspaper.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Why is a public hospital in L.A. restraining psychiatric patients at high rates?

Strapping down a psychiatric patient is supposed to be a measure of last resort for medical professionals. Federal law forbids hospitals from physically restraining patients unless they need to prevent patients from harming themselves or others — and only after other steps have failed.

So the numbers at L.A. General Medical Center were striking to me and to investigative reporter Ben Poston. The public hospital, which serves some of the poorest and most vulnerable people in L.A. County, has been restraining patients in its locked psychiatric unit at a higher rate than any other inpatient facility in California from 2018 to 2021, federal figures show.

In fact, the restraint rate at L.A. General’s Augustus F. Hawkins Mental Health Center was more than 50 times higher than the national average for inpatient psychiatric facilities, ranking it among the highest in the United States during that time. And the numbers have only grown in recent years, doubling between 2020 and 2021.

We teamed up to look deeper. L.A. General officials said that the high rates are tied to forces beyond their control, including more patients with a history of violence showing up at the hospital and longer waits to transfer patients to more suitable facilities.

“We have not been prepared to handle people at this level of violence,” L.A. General Chief Medical Officer Dr. Brad Spellberg said.

Other facilities are unwilling to take the “difficult” patients that it handles as a publicly run, safety net hospital close to Skid Row and the jails, said officials at the L.A. County Department of Health Services, which operates L.A. General.

L.A. General plainly has challenges, but mental health experts we interviewed questioned its explanations for high rates of restraint. Other safety net hospitals in San Francisco and New York City do not restrain psychiatric patients at anywhere near the same rate as L.A. General.

“It doesn’t make sense to me that patients in L.A. are more seriously psychotic and dangerous than patients at a general hospital in San Francisco,” said USC law professor Elyn Saks, who has studied the use of restraints for decades.

We also asked for numbers. Hospital officials said that assaults on staff had risen dramatically. The county later provided figures that do not show an increase in the average number of attacks each month at the psychiatric unit between mid-2018 and spring 2022.

To explain the high rates of restraint, county officials also pointed to a logistical issue that doesn’t exist at other hospitals: Hawkins, the psychiatric inpatient unit for L.A. General is miles away from the main hospital in Boyle Heights, and all Hawkins patients are restrained on the drive between the two. Hospital officials said restraint was needed to prevent patients from jumping out of moving vehicles or harming staff.

Some mental health experts said it was inappropriate to have a blanket practice of restraining all patients from the psychiatric unit during trips to the main hospital. “It’s traumatizing and it certainly doesn’t help gain a person’s trust,” said Kevin Huckshorn, a mental health nurse and national expert on restraint reduction strategies. She added: “Everybody’s not dangerous.”

Marcelus Laidler, 48, was restrained dozens of times while hospitalized at L.A. General in a medical unit on its main campus. (Such episodes of restraint are not included in the federal data, which only includes psychiatric inpatient units.)

Two years after being discharged, he said he still suffers nightmares about being restrained.

“That hospital is like one bad dream after another,” he said.

Today’s top stories

War in the Middle East

- What do Hamas and Israel see as the endgame? What would ‘victory’ look like?

- As rage spreads, dueling narratives from Israel and Hamas highlight the risk of a wider war.

- Doug Emhoff, America’s Jewish second gentleman, on how he navigated tragedy in Israel and Gaza.

Politics

- Jim Jordan loses second vote for House speaker, but vows to try again.

- Jim Jordan is deep in his flop era.

- Los Angeles newscaster Christina Pascucci announces she’s running for Dianne Feinstein’s Senate seat.

More world and national news

- How a solar eclipse threw a remote Utah town — and its Navajo workforce — into crisis.

- After the Maui fire, some Hawaiians rethink the aloha spirit. Is it for tourists, family, everyone?

- Guatemalans have taken to the streets. All they want: For their president-elect to take office.

- Immigrant workers describe the discrimination they face on the job.

Climate and environment

- A fall heat wave is hitting California. How to prepare, and when it will end.

- Black Girl Environmentalist empowers Black girls, women and nonbinary people to be environmental leaders.

- Despite diplomatic tension, Gov. Gavin Newsom is going to China to promote cooperation on climate change.

Education in California

- Most California students fall short of grade-level standards in math and reading, scores show.

- This California school board president has 2 DUIs and cusses. And, no, he’s not resigning.

Business

- Elon Musk says X is fighting bots and spam, and the solution is: $1 subscriptions.

- Disneyland didn’t always embrace Halloween. Once it did? Game changer.

More big stories

- He was beaten to death in Men’s Central Jail. It took staff nearly 4 hours to notice.

- ‘What ticket should I pick?’ Clerk chooses, customer wins millions in lottery.

- Oops! California earthquake early-warning test goes off 7 hours too early for some.

- Rite Aid to close 31 California stores in bankruptcy, pulling out of some cities entirely.

- Detective alleges sexual hazing on LAPD’s Centurions football team.

- Volunteer brigades will help prep for disasters in the area devastated by the Woolsey fire.

- Andy Bales retires after 20 years at the Union Rescue Mission, leaving a final legacy: his house.

- ‘The Accidental Getaway Driver’ roams into emotional territory. I reported the real thing.

- A young Black man, a big dream and the Watts rec center that helped him out of the projects.

Get unlimited access to the Los Angeles Times. Subscribe here.

Commentary and opinions

- Editorial: President Biden should balance support for Israel with pushing for peace in a volatile region.

- Letters to the Editor: Why the war in Ukraine is nothing like the danger Israel faces.

- LZ Granderson: Those campus rallies aren’t just pro-Palestinian. They’re anticolonial.

- Opinion: I’m a former U.S. diplomat who was stationed in Israel. I feel only empathy and pain.

Today’s great reads

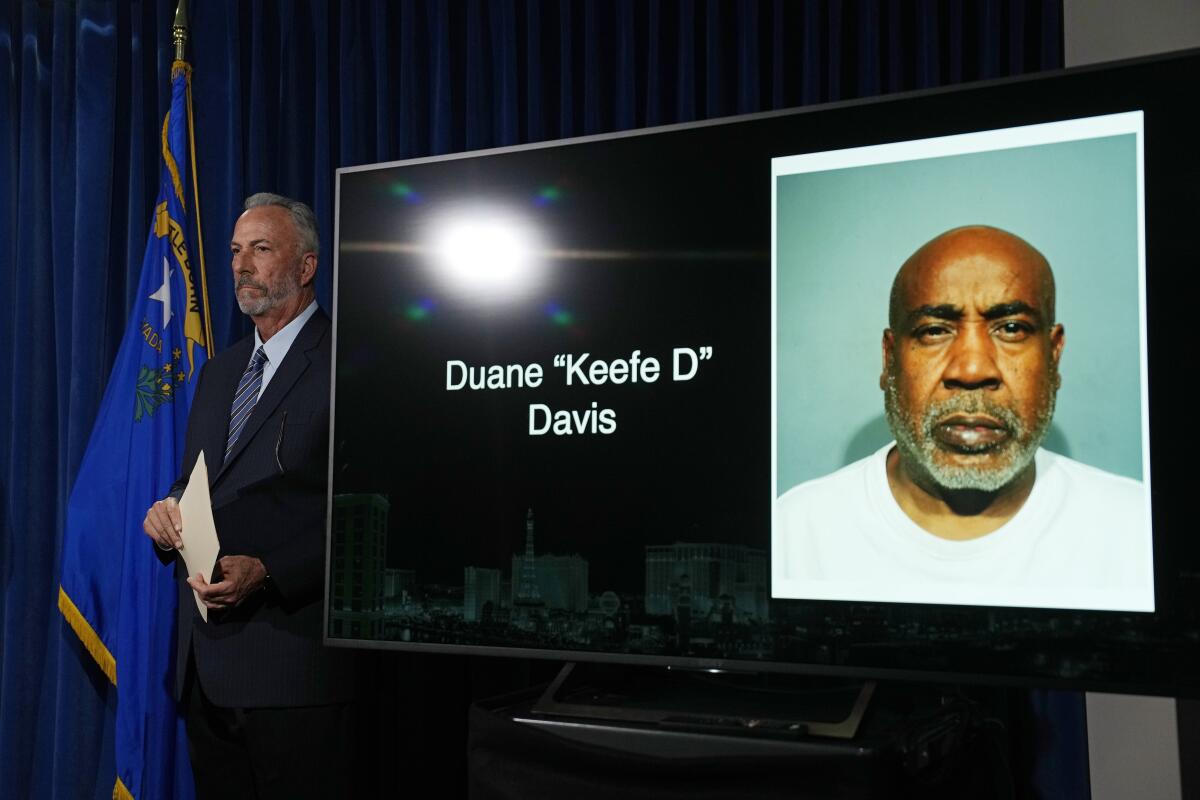

The man who chronicled Tupac Shakur’s slaying is now accused of orchestrating it. When Las Vegas Metro police finally arrested a man in the 1996 slaying of Tupac Shakur last month, some of the department’s most compelling evidence came from the suspect himself. Long before he was charged in Tupac’s death, Duane “Keffe D” Davis had spoken and written extensively about his involvement. “He was the best witness against himself,” former LAPD Det. Greg Kading said. “Ego and greed caught up with him.”

Other great reads

- Why In-N-Out has barely changed its business for 75 years — not even its fries.

- L.A.’s social scene is dead. So I let AI set me up on a blind friend date.

- Estella González’s second novel spans three generations of Latina women. Here’s how she did it.

How can we make this newsletter more useful? Send comments to essentialcalifornia@latimes.com.

For your downtime

Going out

- 👻 10 Halloween events and attractions to rattle and shake your bones.

- 🍚 This popular new Hong Kong-style cafe puts a spin on Taiwanese and Chinese classics.

- 🎞️ Egyptian Theatre announces its reopening date and first wave of programming.

Staying in

- 💿 Allison Russell has been through hell. So why is her new album so damn joyful?

- 📺 ‘Avatar’ live-action series: First look at Fire Lord Ozai, General Iroh and more.

- 🍢 Here are some recipes for tofu.

- ✏️ Get our free daily crossword puzzle, sudoku, word search and arcade games.

And finally ... from our archives

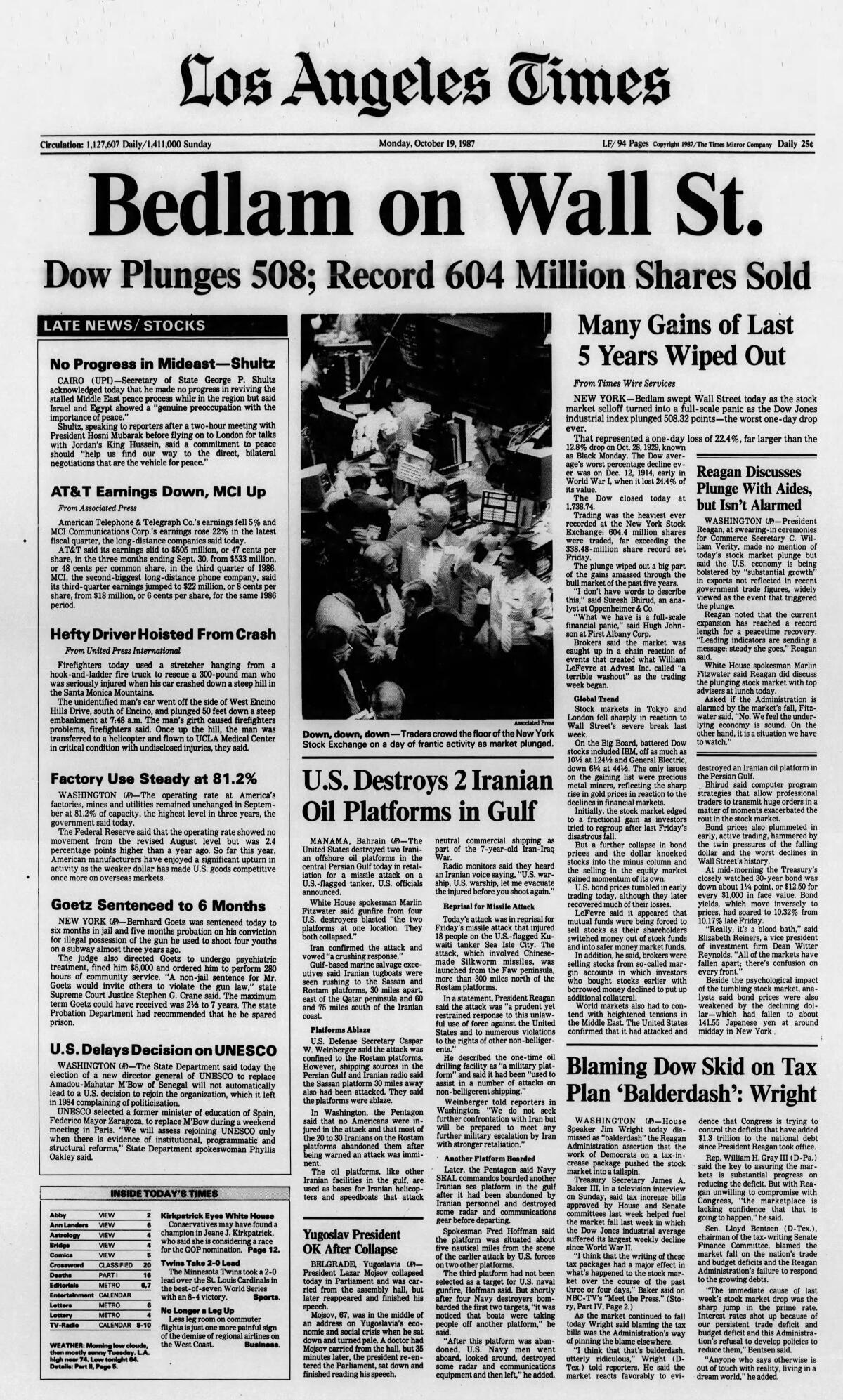

On Oct. 19, 1987, bedlam swept Wall Street as the stock market selloff turned into a full-scale panic as the Dow Jones Industrial Average plunged 508 points (the worst one-day drop ever). It became known as “Black Monday.”

Have a great day, from the Essential California team

Emily Alpert Reyes, public health reporter

Elvia Limón, multiplatform editor

Kevinisha Walker, multiplatform editor

Laura Blasey, assistant editor

Karim Doumar, head of newsletters

Check our top stories, topics and the latest articles on latimes.com.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.