How green are dockless e-scooters?

- Share via

Dockless e-scooter companies have for roughly two years touted their devices as not only convenient but also a win for the environment.

But a growing body of research suggests that the scooter craze may not be as green as advertised.

To change that, experts say, companies such as Lime, Bird and Wheels must manufacture more robust e-scooters while riders need to increasingly use those devices in lieu of driving. According to studies, many people are cruising around on e-scooters as an alternative to cleaner forms of transportation, such as biking, walking and taking the bus.

Still, experts say the fast-evolving industry has the potential to revolutionize urban travel and significantly reduce planet-warming emissions.

“It could be huge for sustainable travel,” said Juan Matute, deputy director of UCLA’s Institute of Transportation Studies.

“When they launched, things were relatively inefficient and messy,” he said. “Now they’re trying to work out some of those kinks, like having vehicles that last longer, but also expanding the vehicle types they offer.”

Some local elected leaders, who are facing increasing pressure from the state to curb vehicle emissions, also have promoted the scooters as environmentally friendly. San Diego Mayor Kevin Faulconer, for example, has called the devices “game changers” that can help the city realize its ambitious Climate Action Plan goals.

At a recent public hearing in San Diego, Katie Stevens, director of government relations for Lime, told members of the City Council that scooters were encouraging people to forgo driving — downplaying the technology’s potential to replace bicycle and walking trips.

“E-scooter are the mode that are successfully getting people out of cars,” she said. “This is an additional segment of the population that’s doesn’t utilize active transportation.”

Data starting to emerge from cities around the country seem to contradict that testimony. About 40% of scooter rides have replaced biking or walking trips in San Francisco and Portland, Ore., according to recent municipal surveys.

A survey from Paris was even more grim, finding that 85% of scooter rides replaced either walking, biking or public transit trips.

User polls have also found that on average about a third of scooter trips are replacing car trips, including a sizable 41% of the time in San Francisco. Lime said that figure is 35% in San Diego.

Given how people are using the devices, the carbon footprint of scooters is very low, but not a net gain for the environment as some companies have suggested, according to a scientific study published in August from North Carolina State University.

“It looks like an increase in environmental impacts … because about half of the scooter rides are displacing walking and riding bikes,” said Jeremiah Johnson, a researcher at the university, who co-wrote the report. “If you are one of the riders who is displacing a car ride, you are almost certainly reducing your environmental emissions.”

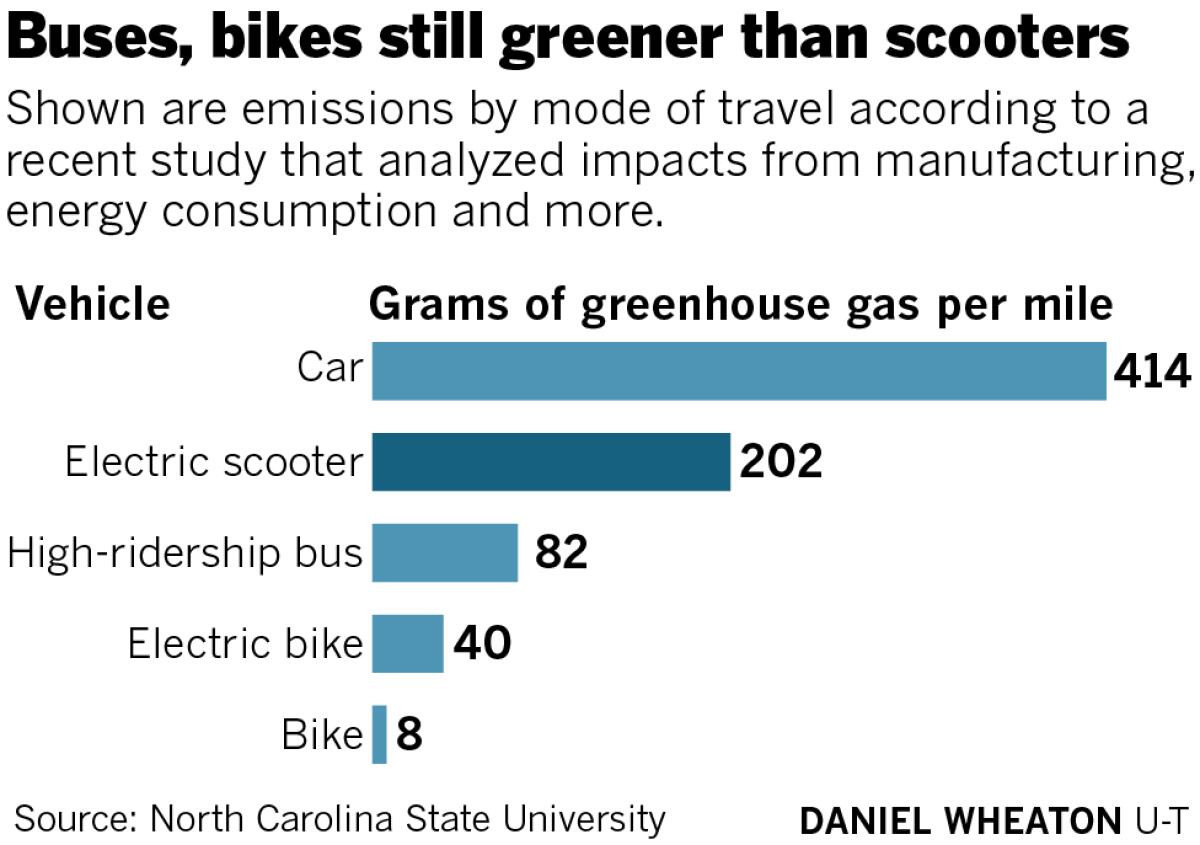

The study, the first of its kind, measured the greenhouse gas emissions per mile for a dockless shared e-scooter and then compared that against the the average car, bus and bicycle.

The life-cycle analysis for scooters took into account emissions created by everything from manufacturing to shipping to disposal to the gas burned while workers drive around searching for scooters to charge and repair. According to the findings, more than 90% of emissions were from building the devices and shuttling them around by car.

That means that making the scooters last longer would go a long way toward shrinking their carbon footprint, Johnson said.

“These are changes that are quite feasible,” he said. “Extending the scooter lifetime, improving the efficiency of the collection and distribution system, those are achievable things. They don’t require new technology. They don’t require enormous changes in the system.”

In fact, companies have been rolling out more robust scooters on a regular basis.

Bird and Lime say their most recent models last more than a year on average. For comparison, the North Carolina study used a median life span of 15 months for its analysis.

While the industry has been tight-lipped about the durability of their earlier devices, research suggests they lasted a month to six months on average.

It makes sense for scooter companies to invest in devices that log more miles before being scrapped for parts, said Andrew Savage, vice president of sustainability for Lime.

“There is a strong business case and environmental case for scooters lasting longer,” he said. “It’s something that we as a company have spent an enormous amount of effort with continuous improvement on.”

Another improvement that some companies are exploring is moving away from the free-for-all collection systems that employ gig-economy workers to compete with one another at the end of the day to scoop up as many devices as possible. The model may provide cheap labor for scooter companies, but it creates a lot of needless driving, according to experts.

In response, some scooter companies, such as the Ford-owned Spin, have started employing workers to round up scooters that need charging and maintenance. This costs more but allows companies to more efficiently deploy their collection fleets.

Spin has also been experimenting with charging stations in places such as Chicago, Tampa, Fla., and Washington, D.C.

“We believe charging stations can make our operations more eco-friendly, in that they’ll limit the number of trips our drivers need to make to pick up and charge scooters,” company spokeswoman Maria Buczkowski said. “Eventually these stations will be retrofitted with solar panels.”

Along the same lines, Lime officials said its company is trying out a new model that allows its freelance drivers to reserve scooters for collection using its app. The result, they hope, will be a better experience for the workers and fewer tailpipe emissions.

Some transportation researchers have questioned whether such tweaks to the scooter industry will lead to any significant environmental gains. Although shrinking the carbon footprint of a device may improve a company’s image, that doesn’t guarantee it will lead to large cuts in greenhouse gas.

“Even if it can have lasting effects on daily travel, unless they connect to transit, the actual vehicle miles that are substituted are just minuscule,” said Dillon Fitch, a researcher who studies travel patterns and commuter behavior at UC Davis. “It’s just a drop in the bucket.”

Still, Fitch said, the dockless bikes and scooters that have flooded city streets around the country may psychologically affect those who routinely drive.

“The big benefit that could be realized by scooter shares are just changing people’s decision processes,” he said. “Just the idea that someone could stop and think before they jump in the car and consider something else, I think is a huge win.”

At the same time, the scooter craze may be kicking off an interest in personal ownership of such devices, experts said. This could also increasingly affect how people think about getting around urban landscapes.

If micro-mobility continues to evolve and gain in popularity, it will raise a host of questions for public officials. The demand for bike lanes could, for example, dramatically increase, and many such pathways may have to be redesigned for vehicles that travel different speeds.

Because the industry is being supported by billions in venture capital, there’s also the chance that it could collapse overnight. It’s far from clear whether public enthusiasm for the devices will translate into profits if companies eventually go public.

That could be especially challenging in cities without comprehensive bike-lane networks, such as in San Diego. The city recently reported that it saw a 50% decline in scooter ridership since this summer, raising questions about the future of the industry.

Smith writes for the San Diego Union-Tribune.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.