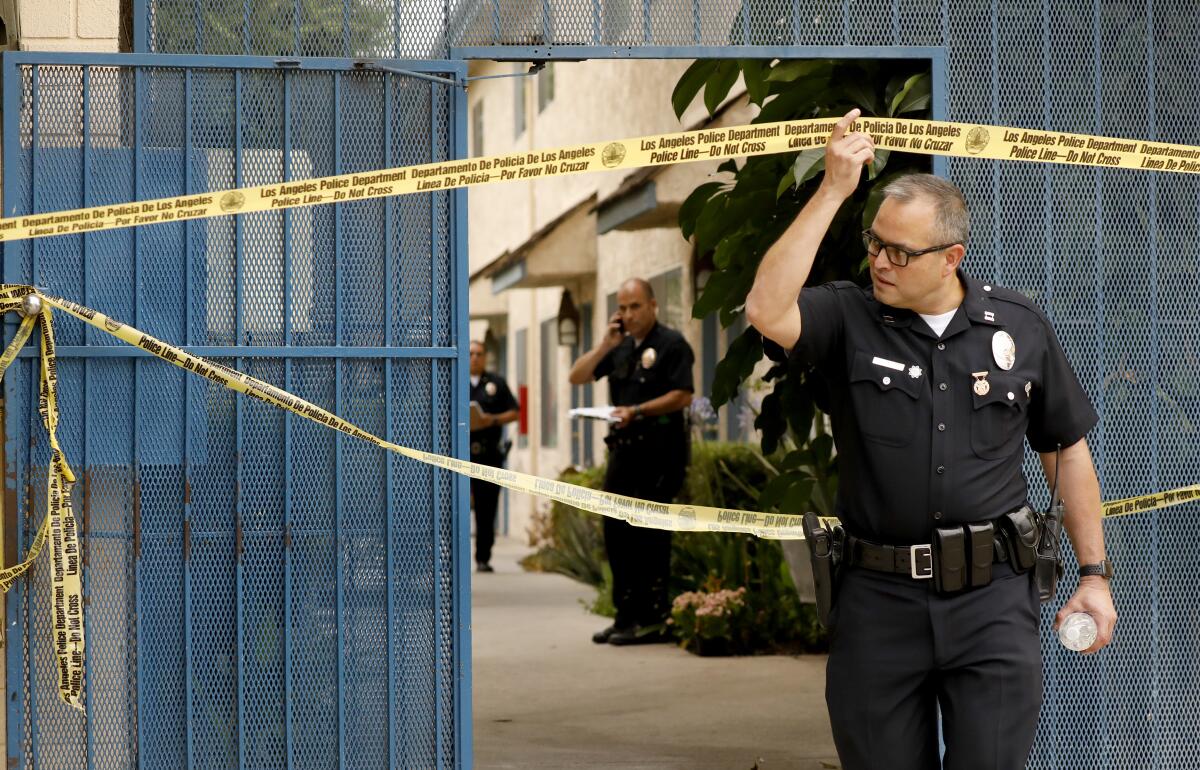

Crime in L.A. dropped again in 2019. Police credit community outreach and gang intervention

- Share via

Violent crime in Los Angeles declined for the second consecutive year in 2019, which was the 10th consecutive year the city saw fewer than 300 homicides.

Gang-related homicides and crime related to homelessness remain persistent trouble spots, officials said. But the overall crime picture continued several positive trends from the previous year, and officials said Los Angeles may be experiencing one of the safest periods in modern history.

Homicides were at 252 as of Dec. 21, the same number as 2018 to that date. Violent crime, including homicides, rape, robbery and aggravated assaults, slid by 3.6%. The number of shooting victims dropped from 985 to 924, a 6.2% difference. Property crimes also decreased.

In the most dramatic decline, reported rapes decreased by 22.6%. But there were questions about how that statistic should be interpreted, and many advocates said that rape remains one of the most underreported crimes.

Los Angeles Police Chief Michel Moore said the crime numbers show the department’s emphasis on community policing is working. Continuing to partner with organizations such as the Gang Reduction and Youth Development Foundation has given the department more opportunities to work at the “neighborhood level,” Moore said.

“This happens when all parts of our community work together,” Moore said. “This is one of the safest times in our history.”

There is no doubt that statistically, Los Angeles is far less deadly than in previous decades: in 1992 homicides peaked at nearly 1,100 and nearly 90,000 violent crimes were reported. In 2019, about 27,000 violent crimes were reported.

Crime also fell in the parts of L.A. County patrolled by the Sheriff’s Department, with murders and burglaries both down about 15%, according to Sheriff Alex Villanueva.

Elsewhere in California, crime dropped by 4.6% in San Francisco, but increased by 15% in Oakland, according to the cities’ police departments. A 12% increase in homicides drove the crime spike in Oakland.

About 57% of 2018’s homicides in Los Angeles were gang-related, according to a 2018 report. That number too was down in 2019.

But Moore said that category, as well as homeless crime, still poses challenges.

“Far too many” crimes committed against and perpetrated by homeless individuals happened in 2019, Moore said. And of the 252 city-wide homicides, he said more than half of them were gang-related.

A LAPD spokesman said the department is compiling the most up-to-date statistics for both categories and will release them in early 2020.

“We have a lot of room to improve on,” Moore said. “Imagine how much safer our city would be if we do.”

Moore has previously touted LAPD-led youth programs and the work of gang interventionists for reductions in gang crime. But gang members themselves also launched initiatives to curtail violence.

After rapper and community activist Nipsey Hussle was killed in March, several South Los Angeles gangs agreed to a tentative ceasefire. Nipsey Hussle, born Ermias Asghedom, rapped openly of his gang affiliation and called for reinvesting in the community and constructive reform in the streets. Many compared the truce to the one in 1992 after the devastating L.A. riots.

Skipp Townsend, a prominent gang interventionist, said the ceasefire has sparked similar talks across the city, which makes him optimistic for the future.

“There are more people talking about peace weekly than there are people talking about being violent again,” Townsend said.

The LAPD defines a gang-related crime as when “the suspect or victim is an active or affiliate gang member, or when circumstances indicate that the crime is consistent with gang activity.”

Townsend said that definition is too subjective and lacks context. Isolated incidents that occur between individuals who also may be in a gang shouldn’t count toward the tally, Townsend said. He acknowledged the department’s work with community organizations, saying that needs to continue. Specifically, he said more former gang members working with police on the ground in communities would help.

“There’s no way a person can show up with a uniform with a badge and a gun and think that he’s making an impact in the community,” Townsend said. “It takes someone who is in regular street clothes, who talks and acts just like them, to say ‘Hey, come on, let’s talk peace. Let’s put the guns down and have a conversation.’”

An LAPD report released earlier this year showed there was a 53% increase in homeless crime as perpetrators, and a 68% increase in crimes involving a homeless victim from 2017 to 2018. Moore said the department would work with city officials on several initiatives, for example, to place more homeless people in shelters and create more storage units for their belongings.

Crimes committed by or against homeless people will not be tolerated, he said.

“We hear the community in their plea for law enforcement to take a more active role,” Moore said.

Police Commissioner Steve Soboroff, a member of the civilian body that governs the department, agreed with Moore’s strategy, saying it’s a way to serve a community that may feel unrepresented.

The fact that homeless individuals are reporting crimes is a good sign, Soboroff said.

“We’re in the business of trust,” he said. “The more people that know that we’re out there, hopefully it will help more people trust us.”

Moore said the department is investigating the steep drop in reported rape cases —1,495 in 2019, which is 436 fewer cases than 2018. It also marks the lowest total in six years.

That data doesn’t reflect national trends, as reported rapes have increased steadily since 2013, according to the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting program. But experts said rape is underreported across the country and in Los Angeles.

“I get a lot of calls from people who say, ‘I didn’t go to the police because I know how I’m going to be treated,’” said David Ring, a sexual crimes and personal injury lawyer in Los Angeles. “They’ll say, ‘I know the types of questions I’m going to be asked.’ At the end of the day, the police are going to say, ‘Sorry, we can’t help you. ’So why do I want to put myself through that?’”

Ring is representing a client in the trial against Harvey Weinstein, the film producer whom numerous women have accused of sexually assault. Experts say the high profile saga, which fueled the #MeToo Movement in 2017, may have encouraged survivors to speak out. But Ring said the “Weinstein effect” has also made the public more aggressive in attempting to discredit survivors’ testimonies, making some of them fearful of reporting to police.

Genie Harrison, a sexual harassment lawyer in Los Angeles who is also representing one of Weinstein’s accusers, estimated that 75% of the survivors who contact her firm tell her they haven’t contacted police. She isn’t surprised the reported numbers are low.

“I certainly don’t see a decrease in the number of people calling my office or emailing me reporting that they’ve been raped,” she said.

Harrison said LAPD should continue recruiting more women and people of color, saying some survivors feel more comfortable talking to someone who looks like them.

Moore said the department will continue its education and outreach on the issue.

“This crime is underreported as a society,” Moore said. “The department wants and needs these people to step forward. These people are important to us, and they matter.”

Moore praised the department’s 70% homicide clearance rate, as well as the 7.8% drop in property crime. Burglaries and motor vehicle theft dropped 16.7% and 11.1% respectively. Soboroff was especially pleased with the LAPD’s efforts to use more non-lethal tools to fight crime, such as the BolaWrap.

Moore said in 2020 he is seeking to hire more civilian across the department to free up uniformed officers for patrols and other pressing needs.

Times staff writer Cindy Chang contributed to this article

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.