‘Tremendous heartbreak’: L.A. Latinos still dying at high rates, even as COVID-19 eases

- Share via

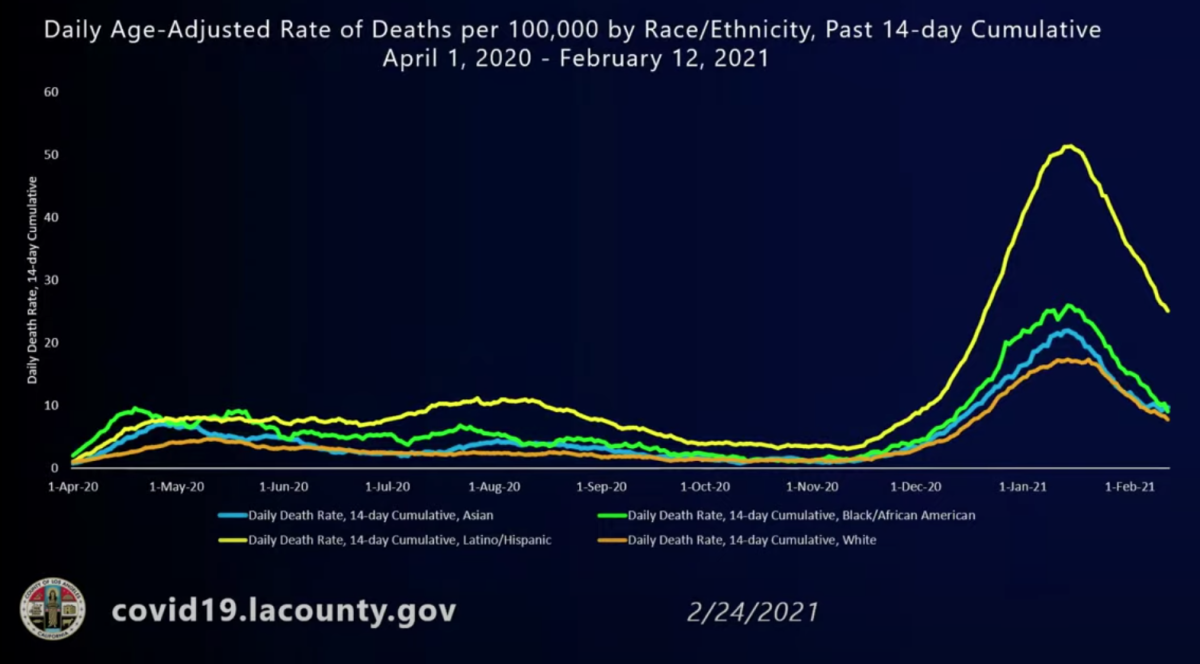

Even as the daily toll of COVID-19 deaths declines, Latino residents of Los Angeles County are still dying at three times the rate of white residents, according to data released Wednesday.

L.A. County is averaging about 111 new reported COVID-19 deaths a day over the past seven days, less than half the rate of the peak of 241 deaths a day recorded in early January, according to a Times analysis.

Over the most recent 14-day period for which data is available, Latinos in L.A. County were dying at a rate of 25 a day per 100,000 Latino residents. That’s still worse than the rate among whites or Asian Americans during any period of the entire pandemic.

According to data analyzed for the two-week period that ended Feb. 12, Black and Asian American residents of L.A. County were dying from COVID-19 at a rate of nine a day per 100,000 Black and Asian American residents; while white residents were dying at a rate of eight a day per 100,000 white residents.

“Our Latinx community is bearing the worst in the pandemic,” L.A. County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer said Wednesday. “While we’ve come to the other side of the terrible surge, it’s important to remember that we did so with tremendous heartbreak, illness and death. I know I speak for everyone when I say we never want to experience the surge again.”

L.A. County data show the death rate among Latino residents remains triple the rate for white residents even as the winter surge fades.

At the worst point of the pandemic in January, the COVID-19 death rate among Latinos in L.A. County peaked at a daily rate of 51 per 100,000 Latino residents, three times worse than the rate for white residents, which was 17 deaths per 100,000 white residents. Black residents in mid-January were dying from COVID-19 at a rate of 23 deaths per 100,000 Black residents; among Asian Americans, the rate was 22 per 100,000 Asian American residents.

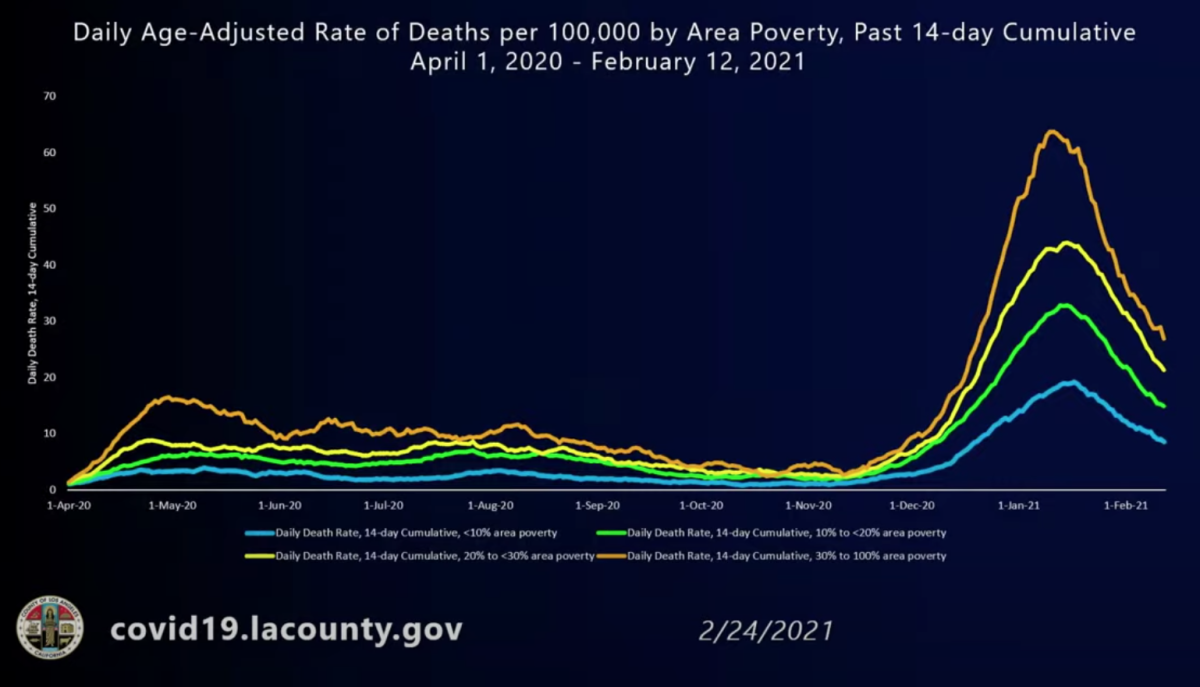

The COVID-19 death rate among people living in the poorest neighborhoods of L.A. County is also significantly higher — about triple — that of people living in the richest areas.

For the two-week period that ended Feb. 12, the COVID-19 death rate for the most impoverished areas was 27 a day per 100,000 residents of those neighborhoods; in the wealthiest areas, the COVID-19 death rate was nine a day per 100,000 residents of those neighborhoods.

At the peak of the pandemic, people living in the most impoverished areas of L.A. County were dying at a rate of 63 a day per 100,000 residents of those neighborhoods.

“I put up this data because it’s a constant reminder that these inequities are very real,” Ferrer said. “We definitely have populations that have suffered disproportionately from COVID-19. The complex set of reasons is really not associated with individual behaviors. [It’s] associated with systematic oppression, racism, lack of resources, and who was actually going to work during the pandemic.”

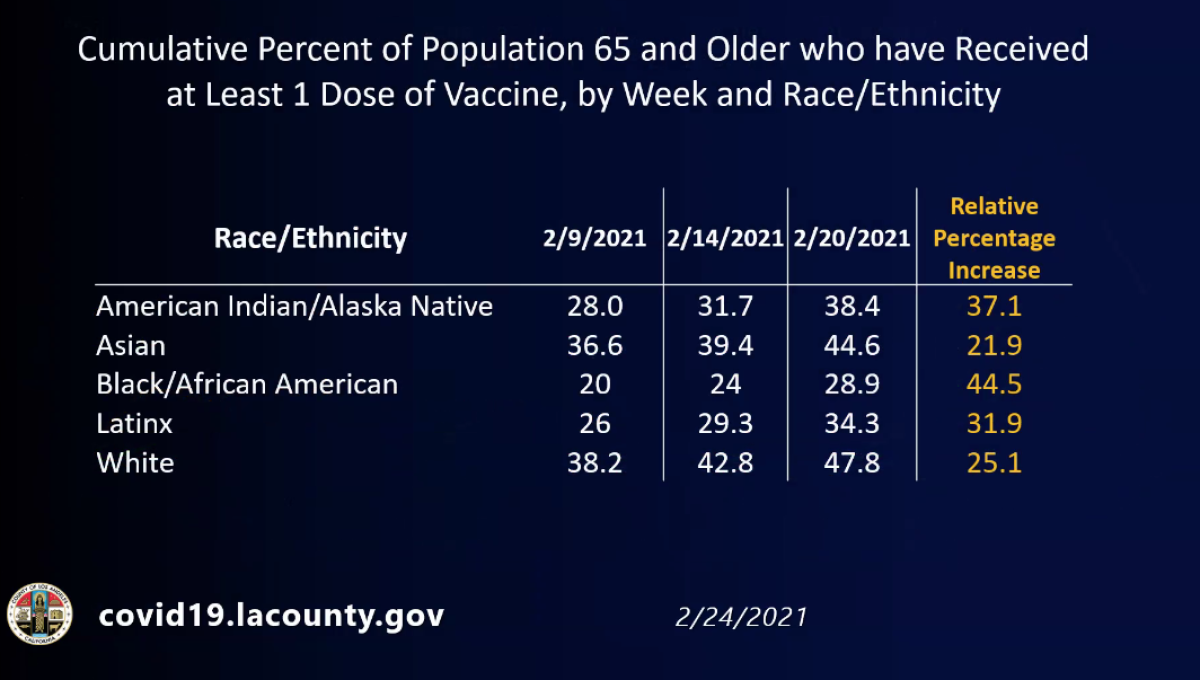

The inequities have extended to vaccinations. White and Asian American seniors are more likely to have received the COVID-19 vaccine than Black, Latino and Native American seniors.

The gaps in vaccination, Ferrer said, “represent inequitable access to vaccines. The shortage of supplies made appointments scarce and difficult to obtain — especially for people who may not have the time or technological ability to register.

Latino and Black communities have been disproportionately hard hit since the beginning of the pandemic. Members of those communities are now dying at rates far worse than at any previous point in the COVID-19 crisis.

“Improving access to areas of the county that have been hard hit is our priority. And these tend to be areas where many Black and Latinx residents live. We have opened additional [vaccination] sites in these areas and we’re working with community groups who are assisting with registering people in these communities for vaccination appointments,” Ferrer said.

For instance, as of the week of Feb. 9, only 20% of all Black seniors in L.A. County had received at least one shot of the vaccine. That number was 26% for Latino seniors and 28% for Native American seniors. By contrast, 38% of white seniors and 37% of Asian American seniors had received at least one dose.

Two weeks later, 29% of Black seniors, 34% of Latino seniors and 38% of Native American seniors had received at least one shot of vaccine. About 48% of white seniors and 45% of Asian American seniors have received at least one dose.

Those results, Ferrer said, demonstrate that efforts to bring more access to vaccines in areas where many Black and Latino residents live is starting to work. Between those two weeks, the relative percentage increase in vaccinations among Black seniors was 45%; among Native Americans 37%; and among Latinos 32%. That’s larger than those experienced by white residents, which increased by 25%, and among Asian Americans, which rose by 22%.

“We are relieved to see these early increases in vaccination rates as they indicate that our strategies may be working,” Ferrer said.

Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti on Wednesday said the city has partnered with trusted community organizations to administer thousands of shots in vulnerable neighborhoods in South L.A., the Eastside, and the San Fernando Valley.

Last week, Garcetti announced a mobile vaccination team, called Mobile Outreach for Vaccine Equity, or MOVE, to expand mobile inoculation services across L.A. Garcetti visited one of the sites in Chinatown, a neighborhood which, despite its location close to a large vaccination site at Dodger Stadium, was found to be in special need of offering assistance to Chinese-speaking and Vietnamese-speaking elderly people who lacked transportation to get to the large site.

“So we set up shop, there in Chinatown, at a parking lot,” Garcetti said. “We saw that work in action with organizations from the community and translators” on hand.

The city will increase to 10 its number of so-called mobile equity sites: vehicles that go out into high-density, low-income communities and provide vaccinations, Mayor Eric Garcetti said.

“These efforts throughout our city reflect our determination to get this right. And to get the right doses to everybody,” Garcetti said. “We’re trying to tear down the structural, economic, cultural and historic barriers that keep people from getting a vaccine or wanting a vaccine.”

Garcetti announced that mobile vaccination teams will begin offering service on Saturdays. “This change will provide additional flexibility to essential workers who work Monday through Friday, who have known that there are vaccine clinics in their communities, but simply couldn’t get to it because they were at work.”

The mayor also warned the public to avoid scams in which people impersonating vaccinators wear medical scrubs and ask for private information and money. “Don’t fall for these tricks, and please report them if they happen to you. No one legitimate will ever ask you to pay money for a COVID vaccine. No one,” Garcetti said.

The federal government is providing the COVID-19 vaccine free of charge to all people living in the United States, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has said.

Lower-income areas are highly susceptible to the spread of the coronavirus because of dense housing, crowded living conditions and a higher proportion of essential workers who are unable to work from home. Officials believe people get sick on the job and then spread the virus to family members at home.

California’s Latino and Black residents and people with an education up to a high school degree suffered among the highest increases in deaths during the pandemic, according to an analysis by researchers at UC San Francisco.

California counties with a greater share of low-wage and crowded households have been hit harder by the pandemic, according to a study by the UC Merced Community and Labor Center. And Latino workers have the highest rate of employment in essential frontline jobs, where there’s a higher risk of exposure to the coronavirus, according to the UC Berkeley Labor Center.

For instance, 55% of Latinos and 48% of Black residents work in such jobs, compared with 35% of white residents.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.