The way we lose Black men never makes sense. Losing my father to COVID is another example

- Share via

In 1988, my father, Gary Evans, earnestly wrote down on a large notecard in blue ballpoint ink “1988 Wishes and Dreams.”

Before tucking the card into the Bible his mother had given him, he listed his 12 hopes for the year. They included getting into law school, relocating from Brooklyn, N.Y., to Arizona with my mother and oldest brother, being popular with people, and the front of his hair growing back. But he also took pains to boldly underline one of his wishes: health for himself and his family.

That was 18 years before his first heart attack. It was 34 years before his heart stopped after complications with COVID-19 and pneumonia. He was 70.

On Jan. 1 my father cheerfully told me he brought in 2022 eating a slice of apple pie. He said “it’s going to be our year” for our family of five. By Jan. 29 I was squeezing his hand tight just hours after he died in the ICU, vowing to hold on until we had to leave him behind.

Since my father’s death, I have stared at the January 2022 calendar page attempting to trace his COVID-19 exposure and when he started coughing. I’ve tried reconstructing timelines and symptoms with dates, texts and calls to understand why my father died. But I know it will not make sense. The way we lose Black men in America never makes sense.

Loving a Black man in America often means your time with them will always seem short-lived. Ahead of my father’s birthday last summer, I told him we had to celebrate, and he replied birthdays were not a big deal. But for Black men in America, every birthday they live to see is a triumph.

Far too many of them never see their 30s, 40s, 50s, 60s and 70s because they are dying too soon from heart disease, cancers, unintentional injuries and now COVID-19. Black people are 2.5 times more likely to be hospitalized and 1.7 times more likely to die from COVID-19 than white people, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics reported in July that between 2019 and 2020, with COVID-19 and other deaths, the average life expectancy for Black men in America went from 71.3 years to 68, a loss of 3.3 years. White men in comparison only lost 1.3 years. The only reason my father beat the average is because of the new calculations.

Death is inevitable, but Black boys and men should not have to live their lives assuming their humanity is debatable. Part of the problem is Black men often wait for care until they’re in dire predicaments, no matter how many people encourage them to do otherwise. We can partially explain this away with many Black men being uninsured or not having a regular doctor.

But we also must recognize how many Black men don’t seek medical care because for generations they have been told verbatim or through societal and political inaction that asking for help or acknowledging emotional or physical pain are signs of weakness. Too often, it’s only when their livelihood or physical well-being is at stake that they start considering their wellness.

My father retired as an adult probation officer two years after his heart attack but would express regret that he hadn’t worked longer. He felt bad about “complaining” about being tired from working two jobs when we were kids. His father, he pointed out, never complained about working late nights as a taxi driver and other jobs in New York. I would reply that just because Grandpa did not say he was tired does not mean he wasn’t.

Saving Black men in America would require a herculean effort by systems and institutions that seems unfathomable in these times. How much longer could they live if they knew the world wanted them to have openly human experiences of breathing, crying, grieving, being cared for and being heard?

While my father was taken by COVID-19, he was by all accounts, a survivor. He survived a heart attack in 2006, kidney and prostate cancer diagnoses in 2009, and a stroke in 2016. He survived two surgeries to install the defibrillator for his heart. He lived with depression and anxiety, both of which were diagnosed when his health issues began at 55. He also had high blood pressure.

One of the hardest truths to reconcile is that my father’s chances for survival — even while vaccinated and boosted for COVID-19 — were slim given his preexisting conditions and how ill he became. My father’s death, particularly as an older Black man, is considered an inevitability we must live with. I can accept my father’s death, but I refuse to accept that the number of Black men we are losing is normal.

My father is now one of more than 6 million people who have died from COVID-19 worldwide. He is now one of the nearly 972,000 people in the United States who died from COVID-19. He is one of the nearly 97,000 Black people in America — and one of more than 87,000 Californians — who have died from COVID-19. He is the second family member we’ve lost to the virus.

My father had the means to access care. He had reliable retirement income, health insurance, a primary care doctor and specialists, medications, housing, transportation, food, internet and an education.

But he could not escape the indignities that came with being a Black man in America. Access meant nothing when his full humanity was not embraced.

The problem with talking about anti-Blackness, racism and healthcare is non-believers only believe explicit acts like patients being called the N-word or doctors loudly refusing to provide care. A 2016 study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found white medical students held outrageous ideas that Black patients have thicker skin and less sensitive nerve endings than white patients and that Black people’s blood coagulates more quickly.

The subtleties of bias in doctor’s offices, clinics and hospitals, especially if Black patients are not hypervigilant, can be stressful, costly, painful and even deadly. Stories of lived and near-death experiences have been passed on for generations and made Black people inherently brace for the worst in their interactions with health providers.

There was the time my father had more questions about getting a defibrillator and the surgeon told my parents, “do not call me back unless you’ve made a decision to do the surgery.” There was the time a doctor told him he had “the heart of an 85-year-old,” a comment that he would often reference with anxiety or anger as a reason for not wanting to go to upcoming appointments.

Once, during a blood test, he tried telling a nurse to use a smaller needle because his veins were hard to find. It was only after digging in his arm with the needle multiple times unsuccessfully that they switched to a smaller one. Another time he found his credit being run to get $4,000 hearing aids. He was overwhelmed by how quickly the store was pushing him to make a decision.

My father was uncomfortable with the idea of inconveniencing people, especially health providers. He dreaded going to the doctor. “They always find something,” he would tell me after mentioning a phantom pain or concerns. That or “well, Marissa, the doctors don’t have a lot of time,” when I encouraged him to ask more questions during appointments.

During his first hospital stay for COVID-19, a nurse poked him four times to draw blood — unsuccessfully — before switching to the top of his hand. He said he “didn’t want to embarrass anybody” by asking for another nurse to try.

I’ve been covering healthcare for nearly a decade, and the foundation of my work has always been observing my father’s healthcare experiences. I wanted to help him. Years ago, when he told me in a Little Caesars parking lot he had two cancer diagnoses, I went home to research cancer mortality rates among Black males and cancer-fighting foods.

When my father turned 65, I studied Medicare policies and clicked around the Medicare website with him to read various plans and helped him pick one.

Two hours before his COVID-19 vaccine appointment last year, he called to tell me he was feeling nervous, and I reassured him the vaccine was safe and an important step for protecting him. He proudly told me later he hadn’t felt the needle go into his arm.

On Jan. 4, my father called telling me one of my brothers thought he should get a COVID-19 test because of his cough. I agreed he should. He was hesitant, but after our collective insistence, he went to CVS the next day to make a test appointment.

On Jan. 6 he got tested, and by late afternoon came the result: positive. I drilled him with questions. Was he still coughing? Did his throat hurt? Any aches? I also had a request: If he experienced any shortness of breath, he had to tell Mom right away, OK?

On Jan. 7 I woke up at 5 a.m. to start driving down to Chula Vista to deliver KN95 masks, lemons, tea, a thermometer, homemade and canned soups, the Costco chicken bakes my father liked and other groceries. I did not step inside my parents’ home. I waved from the door and talked to Dad as he wondered where he may have picked up COVID-19. I told my parents I loved them and drove back to Los Angeles, promising I would return the next weekend.

The week of Jan. 10, my father talked about his consistent cough. He wasn’t sleeping well but said he felt fine, and was lamenting having to stay indoors wearing a mask around the house.

On Jan. 16, the last time I would see him alive in person, he mentioned looking forward to getting another COVID-19 test in a couple of days. We warned he might still test positive and to be prepared.

That day I had brought more KN95 masks and groceries plus a homemade chicken pot pie for my mother to slice for him and a lemon ricotta pound cake. In one of the last text messages he sent me, my father said, “that cake was great, really like it! Thanks so [much] again.”

On Jan. 17, after driving to get in line for a new COVID-19 test, my father passed out in the parking lot from shortness of breath and was rushed to the emergency room. Doctors found he had a co-infection of COVID-19 and pneumonia.

My father was in what he called “a five-star hospital room” by himself. He regaled me on his room phone about the view of the hills from his bed, how nice his nurses were, how pleased he was with the National Geographic magazine my brother bought him and how impressed the nurses were after he told them I worked for The Times. He said he was feeling better and could breathe.

When he left the hospital on Jan. 19 he still was not breathing right, couldn’t sleep and could barely eat. By Jan. 21, he talked about how tired he felt and how the phlegm in his chest was too thick to cough up. By that afternoon he was back in the hospital — this time the same hospital where one of my brothers and I were born — and overnight he was intubated in the intensive care unit.

By the end of the week, my father was making progress, even though he remained intubated. We tried to video call him so he could hear our voices. I soon ran out of daily mundane things to talk about and began reading “The Hobbit,” his favorite book, aloud to him.

Our family was slowly planning as if he would be out of the hospital in a few weeks, including what caregiving at home might look like.

Those plans and hopes died with him. I drove the two hours from Los Angeles to San Diego that evening to say goodbye, hold his hand and read him a couple more pages of “The Hobbit” before he was taken to the hospital morgue. I thought our family would have more time together.

My father deserved more time. He had started making progress on his novel. He hoped to take my mother to Spain. He needed to visit the Vatican. He hoped to see more national parks. He hadn’t finished reading “Dune.” My father would tell anyone he had lived a good life and was proud of his family. But he had more life to live, and I’ll always be heartbroken it was cut short.

Before my father died, I vowed to quadruple my efforts as a daughter if he survived. I’d call more. I’d move closer to San Diego to help with his recovery. I’d drive him to his appointments and Barnes & Noble. I’d sit nearby while he rested or watched ESPN or baseball games with the volume muted, or while he reread “The Lord of the Rings” or books about novel writing.

I miss my father but I’ve thought about what his quality of life might have been had he survived. Would he have needed an oxygen tank? Would he have been able to move around without assistance? Would his depression or anxiety have intensified?

If he had become one of the countless people with long-haul COVID, I am disheartened to think of how much more of a struggle it would have been for my father to advocate for himself.

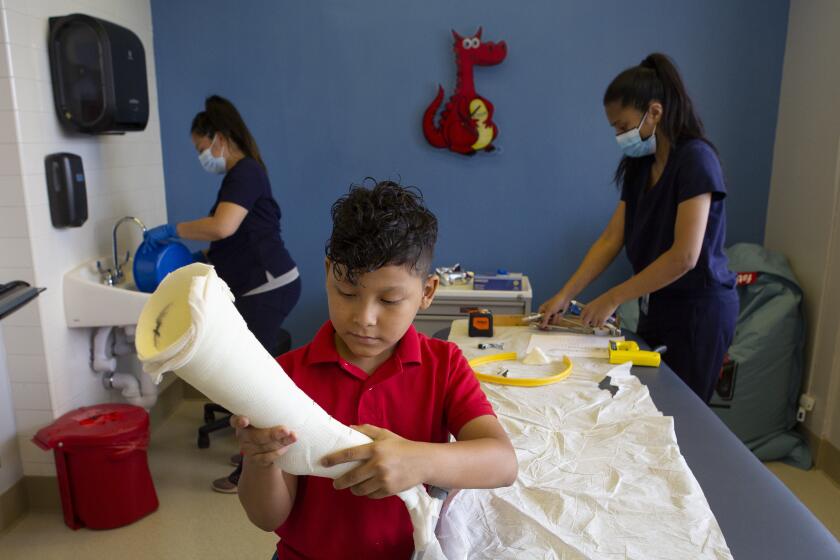

A Mexican boy was born with one leg 11 inches shorter than the other. A remarkable surgery and steadfast friend helped him to walk on his own.

The healthcare system already disempowered my father before the pandemic. It’s hard to believe that would have changed. The prospect of dealing with more doctor visits and tests may have been more of a death sentence to my father.

When my father filled out his notecard in 1988, there was another hope he listed right under the one about health. It was “to be able to speak without fear and to speak clearly, knowledgeably and confidently.”

Knowing my father wrote this in his late 30s, and that decades later he still was working to achieve this, makes me sad. Studying this notecard in the weeks since he died has made it difficult to know if he was referring to something specifically or just generally when he wrote down this wish. I’ll never know now.

But I wish the healthcare system had made him feel like he could fearlessly speak up for the care he deserved.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.